Michael Hill, 58, longtime Regional Rail conductor and forever ‘cool’ dad

Michael Hill is remembered for his big personality and kindness. A North Philly native, he climbed the ranks at SEPTA over a 40-year-career.

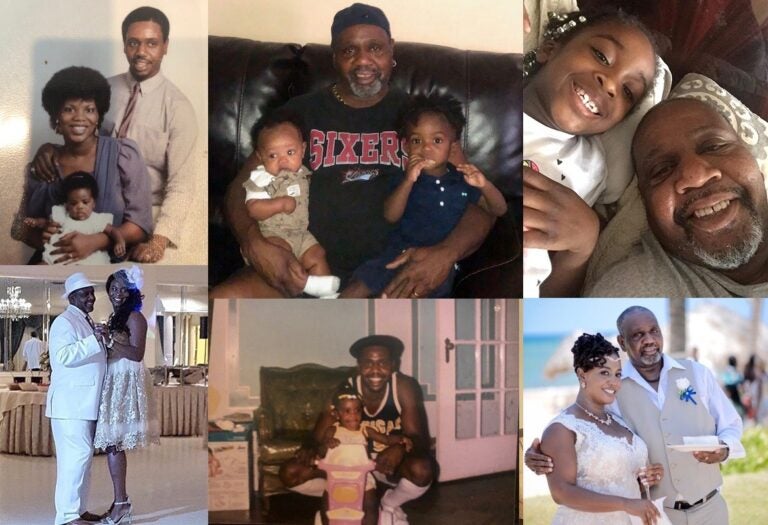

Family photos show Michael Hill through the years from young father to grandfather. (Courtesy of Whitney Samuels)

This story is part of WHYY’s series “COVID-19: Remembering lives we’ve lost” about the everyday people the Philadelphia region has lost to the coronavirus pandemic, the lives they lived, and what they meant to their families, friends and communities.

Marquita Hill remembers the time her father came to her aid in a desperate time of need.

“I was just deadly afraid of this bug that was in my bathroom,” she said. “And I called him in the middle of the night.”

It was 11 o’clock at night when Marquita called her father, Michael Hill, who was asleep in the Glassboro, New Jersey home where she grew up, less than 10 minutes away.

Michael worked for SEPTA as a Regional Rail conductor, an early shift that required him to wake up at 3 a.m. Getting to bed at a decent hour was important to help move passengers within the region. But more important than his duty to morning commuters was that to his daughter.

“He got up in the middle of the night, came and killed that bug for me that was in my bathroom, and went back home,” said Marquita, 35, the oldest of Hill’s two children.

The late-night extermination is one of the cherished memories Marquita Hill conjured to illustrate the kind of relationship she had with her father, who died on April 14 from complications of COVID-19. He was 58.

“He never let me live it down,” she said. “But the fact that he got up and did it for me meant so much.”

Family and coworkers remember Michael as a big, joyful personality. When news of his death hit social media, people he worked with at SEPTA and others who knew him flooded feeds with their admiration and respect.

“He was loved by many,” said Whitney Samuels, his youngest daughter. “Michael Hill was one of a kind. He was really some type of special.”

Michael was born in 1961 in North Philadelphia. He graduated from Benjamin Franklin High School in 1979 and began working for SEPTA in 1989 as an assistant conductor. He was promoted to conductor in 1991 and held the position ever since.

Michael and his family — his wife Louise, along with Marquita and Whitney — moved to Glassboro four years after he became a conductor.

Whitney remembers spending quality time with her father. She says he “not only was my dad, my father, my protector, my provider. He was also a friend, too.” She said even among her friends, their relationship set an example, where they “made it cool to hang out with your dad.”

“We had a great relationship that I didn’t feel nervous to speak to my dad,” Whitney said. “I can look back on a few times of our outings, and just having talks, and me just being able to go to my father about anything … I just enjoyed that he always had that open heart.”

Michael’s family remembers him as a straight shooter, the kind of guy who was “willing to go above and beyond for anybody.”

His younger sister Renee Hill said he was an “easygoing, joyful person” who “made you feel at home no matter what.”

“When my brother entered a room, no matter whose house he went in, he would go in and you would think that was his house,” she said. “He [just] made you feel comfortable no matter where he went at.”

Renee says Michael looked out for her when they were kids. She was a “tomboy,” and he let her tag along with him and their brothers.

She recounted a time Michael and their older brother Terry wanted to play barbershop. Renee was six or seven. There were “plenty of doll babies” to choose from, she said, but they wanted to cut off her two ponytails. And she let them.

“My mother, oh my gosh, she just had a fit when she saw what they did, my two little ponytails laying on the floor,” she said.”It’s those kinds of memories that I will hold on to.”

In addition to his sister Renee and his two daughters, Michael is survived by many family members including Louise, his wife of 37 years, three grandchildren, two brothers, and five nieces and nephews.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.