Meet the ‘Forrest Gump’ of the Revolutionary War at new Philly exhibit

The Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia is opening an exhibition from the perspective of a single British soldier.

A life-sized figure of Richard St. George, a British solider during the Revolutionary War. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The Museum of the American Revolution opened in Philadelphia two years ago to tell the story of the birth of the nation. Next week, it will open its first large-scale exhibition about the other side of the Revolutionary War, the British.

“Cost of Revolution: The Life and Death of an Irish Soldier” focuses on a single British officer: Richard St. George.

“Richard St. George is not particularly famous. He was never a general, never a statesmen, never rose above captain,” said curator Matthew Skic. “But he is one of the most well-documented individuals of this time period.”

Skic sees St. George as the “Forrest Gump” of his day, stumbling — sometimes by chance — into the major global events of his time, just like the Tom Hanks’ character in the 1994 film.

“We’re using his story as a window into this time of great change when a Revolution in America begins to change the way people think about the role of government in daily life,” he said.

St. George was a wealthy, Irish-born gentleman and artist who dabbled in cartooning as a student at Cambridge University. The exhibition includes 10 satirical cartoons he published in London spoofing wealthy people, Cambridge professors, and “macaroni,” the term for extravagantly dapper men who dressed in ostentatious, often mis-matched haute couture.

Later, he got serious. When colonists in America rose up in rebellion, St. George quickly heeded the call of his king and continued to make illustrations as an officer during wartime. His drawings are some of the very few images of the Revolutionary War made on the battlefield.

“Richard St. George came from a tradition thinking that the British Empire is the freest empire in the world. It already had liberty,” said Skic. “But now the Americans are stating there is a new way of thinking about liberty.”

St. George’s wartime drawings were not known to exist until 2007 when they were bought at auction by a private collector in Texas. They have never been displayed publicly before, but St. George’s work may have already been on view — in a way.

“Cost of Revolution” borrows heavily from collections in Ireland and Britain, but draws from the museum’s own collection, including two paintings depicting the battles of Paoli and Germantown. The paintings show very particular details of the battles, including troop movements and known individuals, despite the fact that the artist, Xavier Della Gatta of Italy, had never set foot in colonial America.

Della Gatta was very likely hired by St. George, who gave him his own sketches to work from.

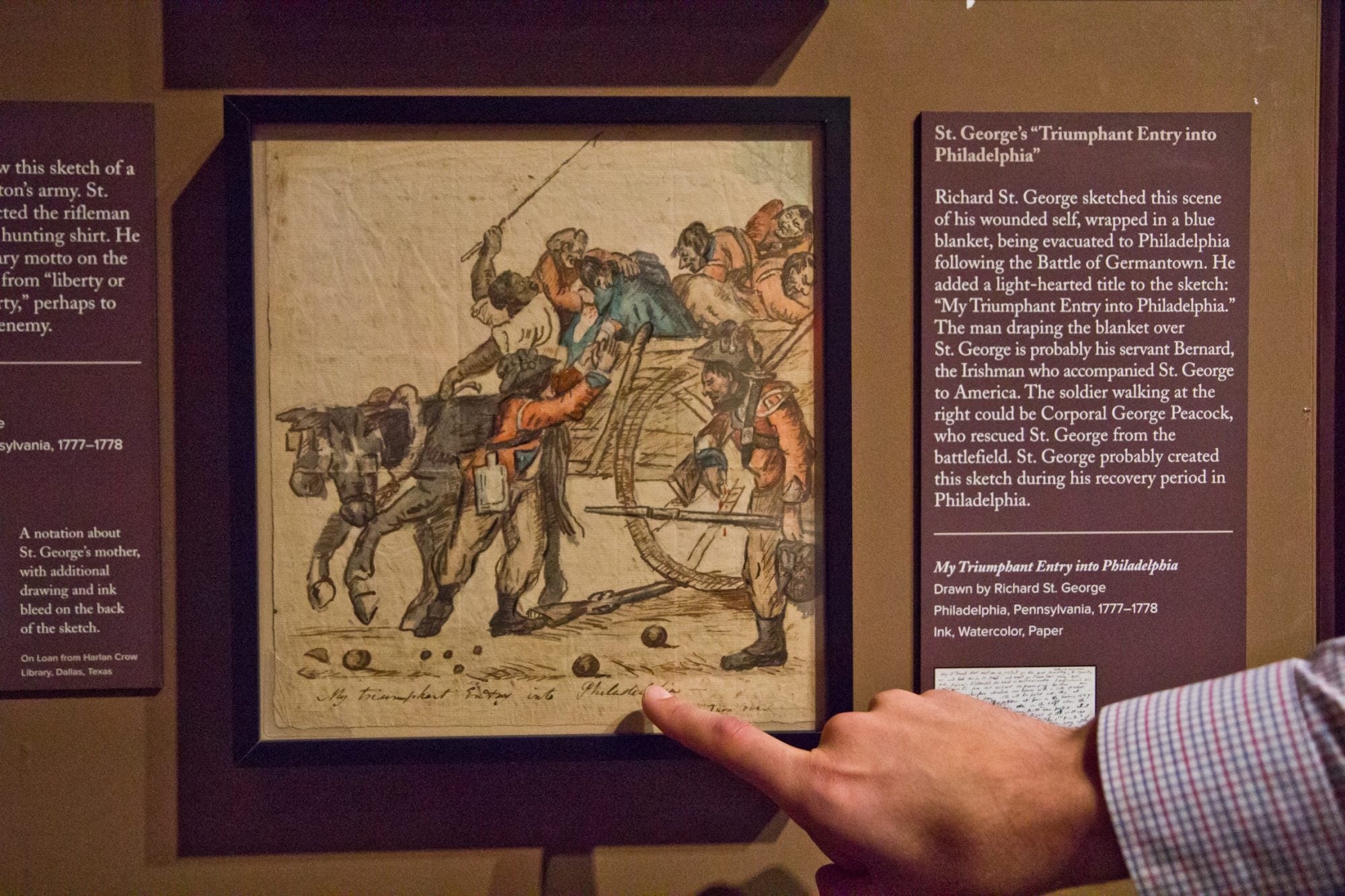

St. George’s ‘triumphant entry into Philadelphia’

St. George did some extraordinary things while he was an officer.

It was not uncommon for African-American slaves to run away from their owners to join the British Army in search of freedom. Usually, they were assigned support duties for the soldiers, such as driving carts, doing laundry, and playing music. St. George set himself apart from other British officers by arming them with guns and swords, making them combat soldiers.

A dramatic tableau in the exhibition shows a figure of St. George commanding an attack. Standing next to him is a determined-looking black man aiming his rifle to fire.

The tableau depicts the Battle of Germantown, where St. George’s career took a permanent turn. He was shot in the head by a musket ball, fracturing his skull. He was carried off the battlefield and carted into British-occupied Philadelphia.

He survived with a silver plate surgically fixed to his skull and his sense of humor intact. He made a sketch of himself being carted into the city with a massive, bleeding head wound. The caption reads, “My triumphant entry into Philadelphia.”

As it turns out, his head would was no joke. St. George was prescribed morphine, which he claimed never fully alleviated the pain. In fact, it made it worse by adding hallucinations and delirium to his ailments.

He would marry and have two children, but his wife died suddenly after just four years. It threw him into a deep depression.

“He was struggling with his post-war life,” Skic said. “He’s turning to art to manage those changes in his life.”

St. George was always sketching and commissioning portraits of himself. The exhibition opens with a large picture of St. George as a young officer and his spaniel named Cocky, ready to set sail for America.

When he returned, injured, he commissioned a portrait of himself in black, wearing a favorite black silk hat to hide his head wound. Then, he commissioned yet another portrait of himself mourning at his wife’s grave.

“He certainly had a dramatic flair,” Skic said. “He was able to afford portraits of himself by the best artists of the time, like Thomas Gainsborough and Hugh Douglas Hamilton. Still, it was unusual to commission so many portraits.”

The Forrest Gump of his time

The exhibition also includes an Irish newspaper that printed the American Declaration of Independence — an artifact reflecting the most dramatic turn of St. George’s life.

In 1794, St. George reactivated his commission as a British officer to face a growing unrest among Irish peasants. The United Irishmen, who were inspired by the American Revolution, began to organize a groundswell against the crown that would become the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

That year, St. George visited his vast 12,000 acres of property in County Cork and chastised his tenants not to join the uprising. He was prepared to punish anyone who was sympathetic to the United Irishmen.

Then, he announced he would be staying the night in the home of one of his tenants.

“He was daring his tenants to try him, and they did,” said Skic. “On Feb. 9, 1798, a group of tenants said to have been influenced by the United Irishmen broke into the house and murdered Richard St. George.”

News of his death quickly spread through all the papers of Ireland and England. The preacher at his funeral made a fiery speech about the danger the rebellion promised and the “bloody Moloch of French adoration.”

St. George’s killers, seen by some as revolutionaries, were identified, tried, and executed.

“His death may have inspired others to act,” Skic said. “His death was one of the first, but not the last wealthy Protestant landlord to be killed.”

In the end, the Irish Rebellion of 1798 was not successful. After six months of civil war, which claimed about 30,000 lives, the revolution was squashed. The Irish Republic would have to wait another 120 years to finally break away from the British crown.

Such is the cost of revolution.

The exhibition opens on Sept. 28 and runs through March 17, 2020 at the Museum of the American Revolution in Old City.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.