Mandela’s South Africa makes case for potency of economic sanctions

Listen

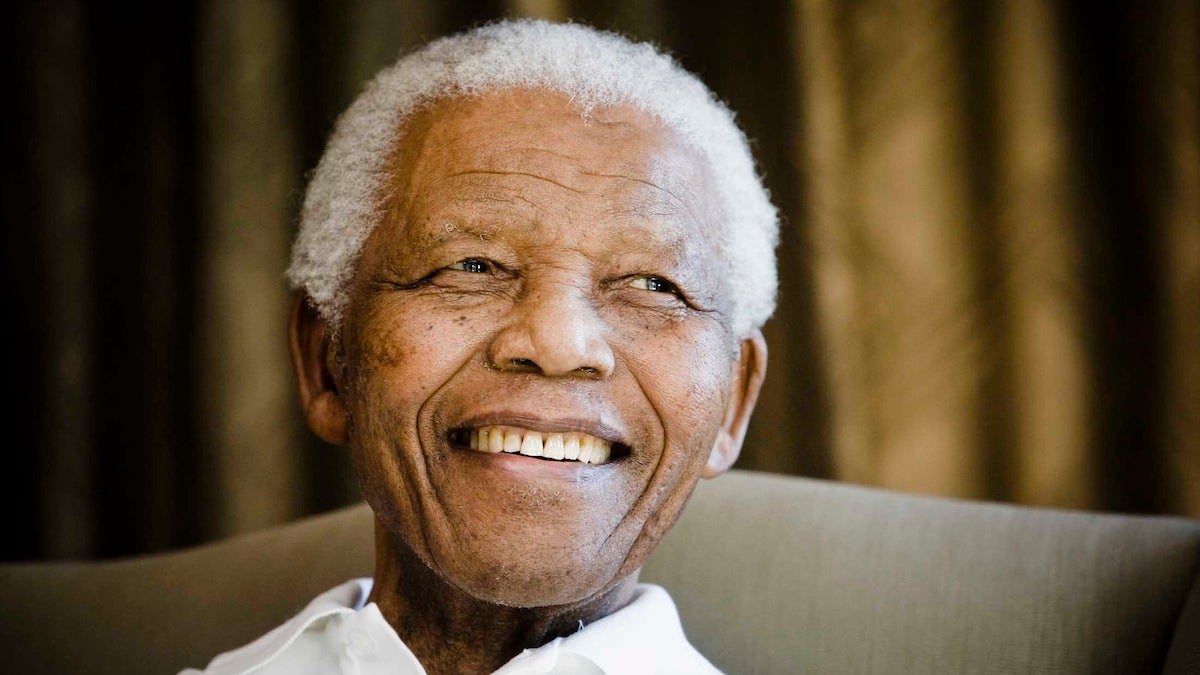

(AP Photo/Pool-Theana Calitz-Bilt, Pool)

In 1993, on the eve of black majority rule in South Africa, Time magazine asked Nelson Mandela if economic sanctions against the country helped speed the demise of its apartheid system. “Oh, there is no doubt,” Mandela replied.

Throughout his 27 years in prison — and right up until he assumed leadership of the new South Africa — Mandela was an unequivocal supporter of sanctions as a weapon of global justice. Yet we’ve heard almost nothing about that legacy amid all the paeans to Mandela, who died on Dec. 5 at the age of 95.

That reflects our own cynicism about sanctions. From Iran and Syria to Cuba and North Korea, the conventional wisdom goes, American and international sanctions haven’t accomplished their goals; if anything, they’ve made things worse.

And in some cases, that’s true. More than a half-century after the U.S. slapped sanctions on Cuba, for example, Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl remain firmly in power. But as the South African example attests, sanctions can also be a force for progress and change.

That’s what exiled African National Congress leader Oliver Tambo told Nelson Mandela in the 1980s, near the end of Mandela’s prison term. “Don’t maneuver yourself into a situation where we have to abandon sanctions,” Tambo wrote Mandela, who had opened secret negotiations with South African president P. W. Botha. “We are very concerned that we should not get stripped of our weapons of struggle, and the most important of these is sanctions.”

So Mandela held firm on that. And after he was released in 1990, he continued to press for sanctions against South Africa. “To lift sanctions now would be to run the risk of aborting the process towards the complete eradication of apartheid,” Mandela declared, in his first public speech upon leaving prison.

And he repeated the message later that year in his triumphal trip to the United States, which had instituted sanctions on South Africa, over president Ronald Reagan’s veto, in 1986. Like many opponents of sanctions today, Reagan insisted that they would harm — not protect — the victims of oppression.

Mandela wasn’t having it. “We still have a struggle on our hands,” Mandela told a joint session of Congress, insisting that sanctions should remain in place. And the following year, when President George H. W. Bush lifted them, Mandela blasted him for acting prematurely.

Only with the establishment of a 1993 transitional executive council in South Africa would Mandela call for an end to sanctions. Yet he continued to claim that they had provided an important boost for black freedom in South Africa, praising the “millions of people across the globe” who had demanded them.

Those people included a young African-American at Occidental College named Barack Obama, who spoke at a 1981 rally condemning the college’s investments in companies that worked in South Africa. “I am one of the countless millions who drew inspiration from Nelson Mandela’s life,” President Obama recalled, after Mandela died. “My very first political action, the first thing I ever did that involved an issue or a policy or politics, was a protest against apartheid.”

But it was also a protest against Americans who did business with apartheid. I participated in similar divestment rallies over the next two years at Columbia, where Obama became my classmate. We didn’t know each other, but we both believed that blocking economic activity in a tyrannical country could make it better.

And there’s plenty of evidence that we were right, in South Africa and elsewhere. Consider Iraq, which was placed under tough sanctions by the United Nations after it attacked Kuwait in 1990. George W. Bush insisted that Saddam Hussein had evaded the sanctions and acquired weapons of mass destruction, which became a key pretext for the American invasion of Iraq in 2003.

But weapons of mass destruction were never found, of course, suggesting that the sanctions worked more than we knew. In Iran, likewise, sanctions surely played a part in forging the recent nuclear pact with the United States. We still don’t know if Iran will actually limit its nuclear program, as it promised. But the promise itself stemmed — at least in part — from international sanctions, which brought Iran to the bargaining table in the first place.

So the next time you hear some pundit on TV say that “sanctions never work,” think again. Think of a youthful Barack Obama, whose protests helped remove a hateful regime from South Africa. And think most of all of Nelson Mandela, who never doubted that all of us could join hands to change the world.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.