Making sense of our “Makeshift Metropolis”

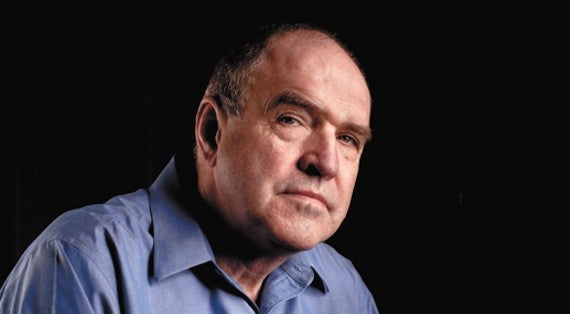

Witold Rybczynski, author, pundit, and Penn professor of urbanism, makes no secret of where he’s chosen to live since moving to Philadelphia: it’s Chestnut Hill.

I’ve always found it a rather curious preference for a man who calls himself an urbanist. After reading his latest book, and listening to his lecture at the Center for Architecture’s Wednesday evening launch party, the reason is clear.

That leafy neighborhood — with its tidy main street and lovely schist homes, its sense of being more of the suburbs that it abuts than of the city that surrounds it — is, really, a “Garden City.”

And, it turns out, Rybczynski very much likes that style of planning, perhaps more than he’d care to admit.

The concept is but one of several 20th-century planning movements that Rybczynski explores in his new title, “Makeshift Metropolis: Ideas About Cities” (Scribner).

In what amounts to a sort of primer, the book also covers Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre, and the City Beautiful Movement realized by Daniel Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and created, Rybczynski says, by journalist Charles Mulford Robinson.

Another journalist, Jane Jacobs, of course, rounds out the pantheon.

As in his book, Rybczynski kicked off his presentation by introducing each of these influencers. It was a step that seemed rudimentary, given the heavy concentration of design students and professionals in attendance.

The set-up, though, is necessary since Rybczynski’s ultimate premise is that planners have become largely irrelevant in the day-to-day operations of today’s city. “Hence the title of my book,” he said Wednesday.

“American cities don’t seemed planned at all,” Rybczynski explained. “We’ve approached the city as a kind of a business, and stuck in whatever we needed into a grid.”

After running through the ideas and showcasing examples, such as Washington, D.C.’s Union Station (City Beautiful, 1907) and Forest Hills, Queens (Garden City, 1909), Rybczynski moved onto, as he does in his book, some of his more trenchant observations.

First, was his enlightening take on how, as part of the “makeshift metropolis,” these ideas have been adapted in our own times — often in unexpected fashion, and not always in the ways in which their crafters might have envisioned.

For example, while Corbu’s notions are widely skewed as ridiculous, everything from the failed housing projects of the post-WWII era to the underground concourses and overhead skyways of the 1970s and 1980s to today’s luxurious lakefront Chicago towers owe him a debt.

And, Rybczynski asks, what is New Urbanism but a spin on the Garden City?

The Bilbao Effect isn’t all that different from the City Beautiful, he further suggests. Each relies on knockout structures as urban saviors.

Isn’t every suburban development, from the Levittowns onward, a version of Broadacre City?

And what about the beloved Ms. Jacobs? Rybczynski sees her depiction of the idealized downtown as one of mixed-use walkability repeated in today’s “lifestyle centers,” such as Reston Town Center in far suburban D.C. The linking of Jacobs with such a project may be horrific to many ears — Rybczynski admits she’d probably view these insta-cities as too artificial — but his point is that today “planners don’t create cities in America, developers do.”

He adds that Jacobs — with her disdain for the planning profession and for things overly planned, as well as her solid grounding in the economic realities of cities — might ultimately appreciate what’s been happening. “Hers was an economic argument,” he said. “When you plan, things go wrong.”

At this point in the book, Rybczynski addresses the very interesting idea of “the kind of cities we want.” Unfortunately, he didn’t delve into it on Wednesday, but the chapter offers some of his keenest insights, including the American preference for the new over the old, the warm over the cold, the dispersed over the condensed, and the small over the large.

The second set of arguments that Rybczynski makes in this chapter concern the nation’s much-vaunted downtown revitalizations. He rightly points out that a successful downtown probably needs a residential population of about 50,000 to “achieve a truly urban way of life” and that only six — downtown and midtown Manhattan, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago and San Francisco — make the cut. “Such highly touted examples of downtown revival as Seattle and Portland, Oregon, are well below the line,” he adds. “So are Cleveland and Pittsburgh.” He then mentions Dallas and Denver, but could add others: Minneapolis, Houston, and Atlanta, come to mind.

Even though Rybczynski is suggesting that we may not really like big, dense urban living — after all, he notes, fewer than one million, or about .3 percent of the entire population actually live in downtown business districts — his observation is an important counterpoint to all of the hype surrounding the resurgence of the American downtowns.

I’ll grant it, even if it does come from a Garden City favorer.

Before accepting questions, Rybczynski introduced three contemporary large-scale developments that, he said, are putting all the pieces of his thesis together. Brooklyn Bridge Park, by Michael Van Valkenburgh and Associates, is the result of a neighborhood, not municipal, initiative. It is market-driven, with revenue-generating, non-park uses such as housing.

In Washington, D.C., The Yards, a redevelopment of a former navy yard along the Anacostia River, by Robert A.M. Stern Architects, is reintroducing streets that had been closed during the site’s former use. It emphasizes mixed-use and density, while incorporating historic elements.

Between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, the new town of Modi’in, by Moshe Safdie and Associates (Safdie is the master planner), strives to look organic and unplanned. Safdie has encouraged a varied slate of designers and developers to have their way.

When one audience member asked the author what he saw as the role of planners for the future, Rybczynski answered: “not a very big one. “In the last fifty years,” he continued, “it’s the developers who have been influential. They have the idea — ‘let’s do the Atlantic Yards’ (the $5 billion Forest City Ratner project in Brooklyn). Developers see opportunities,” Rybczynski said. “They have their finger on the pulse of what the public wants.” (Note to Witold: that particular project has been under attack by neighbors for years.)

Another attendee challenged Rybczynski as to whether or not planners could ever be credited with developing “central strategies that are important in allowing cities to regenerate themselves.”

Rybczynski, who had earlier provided an example of planners’ wrong-doing (“I doubt it was a developer who thought up the idea of the pedestrian mall.”), paused for a moment.

He then offered a bone, saying that in areas such as transit and in tying things together, planners certainly remained necessary. “But,” he added, “on the strength of the last 100 years, the public sector has proven itself incapable of figuring out what people want. It’s very good at telling them what they they should have.”

It seemed a sour note to on which to end the evening, and Rybczynski seemed aware of that. After all, planners may have lorded it over neighborhoods in the past, but with such a strong emphasis on public meetings and citizen planning these days, haven’t such godlike tendencies been tempered?

Contact JoAnn Greco at www.joanngreco.com

Check out her new online magazine, TheCityTraveler at www.thecitytraveler.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.