Making sense of Pa. school funding: budgets, formulas and stalemates

Listen

Pennsylvania House Majority Leader Dave Reed, R-Indiana, speaks to members of the media after Gov. Tom Wolf delivered his budget address for the 2015-16 fiscal year to a joint session of the Pennsylvania House and Senate March 3 in Harrisburg, Pa. (Matt Rourke/AP Photo)

In sight of the state’s budget deadline of July 1, education funding for Pennsylvania schools is still a question mark.

Over the weekend, legislators held 12-hour sessions and advocates flooded the Capitol in Harrisburg to work on a deal, but Democrats and Republicans have shot down each other’s plans. Swirling through the budget debate are two questions that will have a big impact on schools’ bottom lines: How much money should the state contribute to education this year? And what to do with the new education funding formula?

Let’s start with the budget. Gov. Tom Wolf unveiled his budget in March with a promise of an additional $400 million for basic education funding. There’s more money for higher education and pre-kindergarten, but basic education is the simplest way to break out the state’s contribution for regular K-12 funding. It’s also the bread and butter for the districts that aren’t able to raise as much from local property taxes, generally poor and rural districts.

The state House of Representatives has approved the GOP’s counterplan. It would contribute $100 million to basic education funding, and another $20 million to special education, while boasting “no new taxes.”

A spokesman for Sen. Vincent Hughes, D-Philadelphia, said Democrats have poked some significant holes in the GOP budget.

“We believe that this budget only provides an additional $8 million for public education,” said Ben Waxman. “And the reason for that is there are a couple of gimmicks and sleights of hand in the legislation that are going to wind up eliminating even the very modest increase.”

Those “gimmicks,” he said, include restructuring $87 million in Social Security payments and $25 million in pension burdens to effectively erase $112 million of the $120 million for basic and special education funding.

Republicans have a different view. “Eight million dollars is a fallacy,” said Sen. Pat Browne, R-Lehigh. He said Democrats are cherry-picking budget items to reduce the appearance of Republican’s contribution to education.

Gov. Tom Wolf has said he would likely veto — in whole or in part — the Republican budget as it now stands. Democrats and Republicans have already voted down the governor’s tax plan. If a veto does happen, it’s likely both sides will come back to the table after the Fourth of July holiday and start to seek a compromise.

Rep. Mike Vereb said new taxes — if they happen — would likely result in more money for education. “We’d love more money. I think anyone would love more money,” said Vereb, R-Montgomery.

In the meantime, he said, the Legislature recognizes the fact that how it spends money now isn’t fair.

“With education there are areas that need more money than others,” he said. “That’s the [funding] formula that we came up with.”

The funding formula, or how much should districts get and when

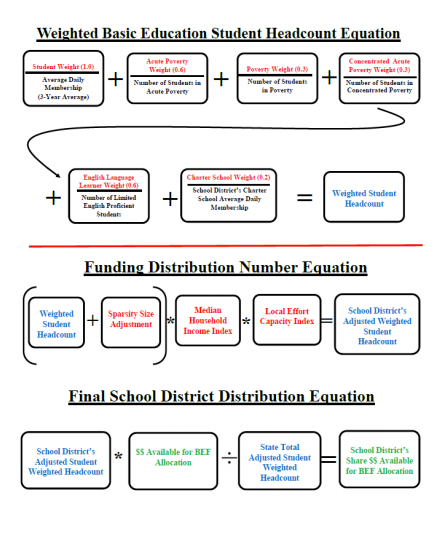

In the plainest sense, a funding formula is just that. A bipartisan state committee came up with a series of factors, such as the number of students in the district and how many of them live in poverty, and assigned each factor a value. When it comes time to divide up the pot of basic education funds, be it large or small, the state multiplies and divides the total amount by those factors to determine how much money each district will receive.

Education advocates and politicians alike praise the new formula for taking into account characteristics of districts, including how widespread the population might be, and students, such as whether they’re learning English. Both factors affect the cost of educating students.

That’s largely where the consensus ends. Not only is the Legislature debating how much money should be funneled into the formula via basic education funding, but advocates and politicians have very different ideas of when the formula should kick in.

Wolf has proposed a “restoration” budget for 2015-2016. Under that plan, school funding would not be determined by the formula but instead be restored to the districts that had the biggest cuts in recent years. That would mean about a third of his proposed $400 million would go to Philadelphia. Every year after next year, districts would get money through the formula.

For full background on the history of the funding formula, check out NewsWorks/Keystone Crossroads “Multiple Choices” series.

Meanwhile, Republican legislators, including Vereb, want to use the formula now that Pennsylvania finally has one.

“I’d like to see the formula implemented right away, not because it’s going to give more or give less to certain areas, but I just think our school boards need predictability,” he said.

Education advocates, watching the recent formula developments, have their own ideas. Many, such as Susan Gobreski, executive director of Education Voters for PA, focus on the fact that just dividing up new money and not the $5.7 billion the state already spends on education doesn’t go far enough to fix funding inequality.

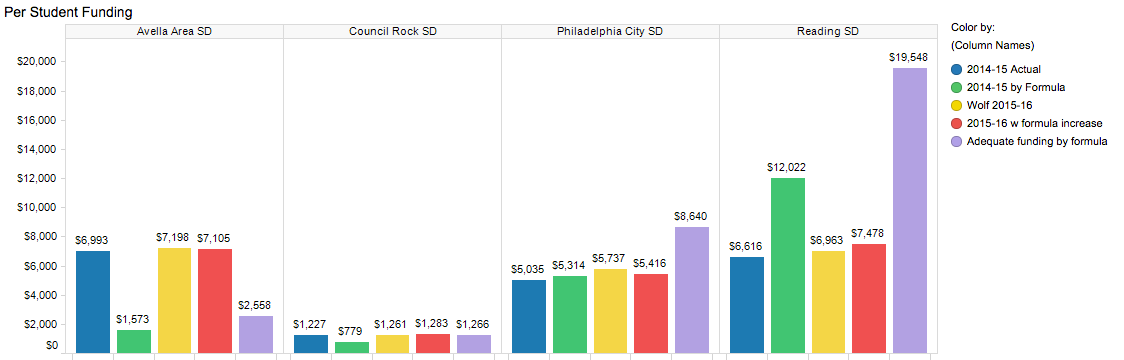

In Pennsylvania, districts with the same number of students or same amount of poverty might get wildly different amounts of state funding.

“The formula is good, and it is fair. but we are starting with an inequitable base,” said Gobreski. “It could take 25, 30, 35 years if you’re just doing little minor tweaks on small bits of funding every year.”

Under Wolf’s plan, she said, the state could get back to a more equal plane in three or four years with lots of investment. “We put some money in now, we can start to adjust that inequitable base and then start to use the formula in an equitable way as we move forward.”

Others suggest a more gradual phasing in of money to districts that experienced cuts, getting to an equitable distribution of funds more slowly.

Another option proposed

Perhaps most radical — and some say most just — would be dividing up all of the state’s education dollars using its own fair funding formula. That would result in some districts getting less than they have now, which is currently illegal under the “hold harmless” clause in the Pennsylvania legal code.

POWER, a faith-based nonprofit, advocates dividing up all of the funds and pushing a larger-than-proposed funding increase, which it says would bring the state to full and fair funding.

In a statement, “POWER stands behind the recommendation of the Campaign for Fair Education Funding, whose study earlier this year determined that a total budget of $9.3B, an increase of $3.6B over the current year’s budget of $5.7B, would be required to achieve adequate funding for all districts.”

Here’s a chart that gives a sense of what these dollar amounts could mean for individual districts: one rural, one suburban, one large, distressed urban district and one small, distressed urban district.

(Thank you to David Mosenkis for help with the graphic.)

In the mad dash to the legislative finish line, it’s not just money that’s on the table for schools.

Over the weekend, the Senate voted through a bill that would create a state-run “achievement district” for schools performing in the lowest 1 percent statewide.

“More money alone will not fix schools in the bottom tier of performance,” said executive director of PennCAN Jonathan Cetel, who lobbied for the bill. “These are schools that when there was more money in the Rendell years, were actually decreasing in proficiency.”

He said the ability go give the state “surgical” ability to take over individual schools, not whole districts, makes it different from state-run districts Chester and Philadelphia.

The bill does not provide any additional financial support for schools that are taken over. Tweeting during the vote, Waxman called the bill a “bad piece of legislation … designed to fail and to help private operators make money off of students.”

The Assembly is also considering a bill that would revise cyber-charter funding statewide, as well as privatize state-run liquor stores and reform pensions to ease the state’s burden.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.