Major art exhibit shows Henri Matisse’s influence on American artists

Many seeking to satisfy a craving for the artwork of Henri Matisse need go no further than Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation. With 59 paintings by Matisse it is one of the largest collections in the world. Those willing to travel a bit further can get their fix at the Baltimore Museum of Art, with 500 works by Matisse in the renowned Cone Collection.

Now through June 18, the Montclair Museum of Art in Montclair, New Jersey has put together an extraordinary alternative, with Matisse and American Art.

Now through June 18, the Montclair Museum of Art in Montclair, New Jersey has put together an extraordinary alternative, with Matisse and American Art.

For this major exhibition of the 20th century master, works have been borrowed from the Brooklyn Museum, the Hirshhorn Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Museum of Modern Art, National Gallery, the Newark Museum, Philadelphia Museum of Art and many others.

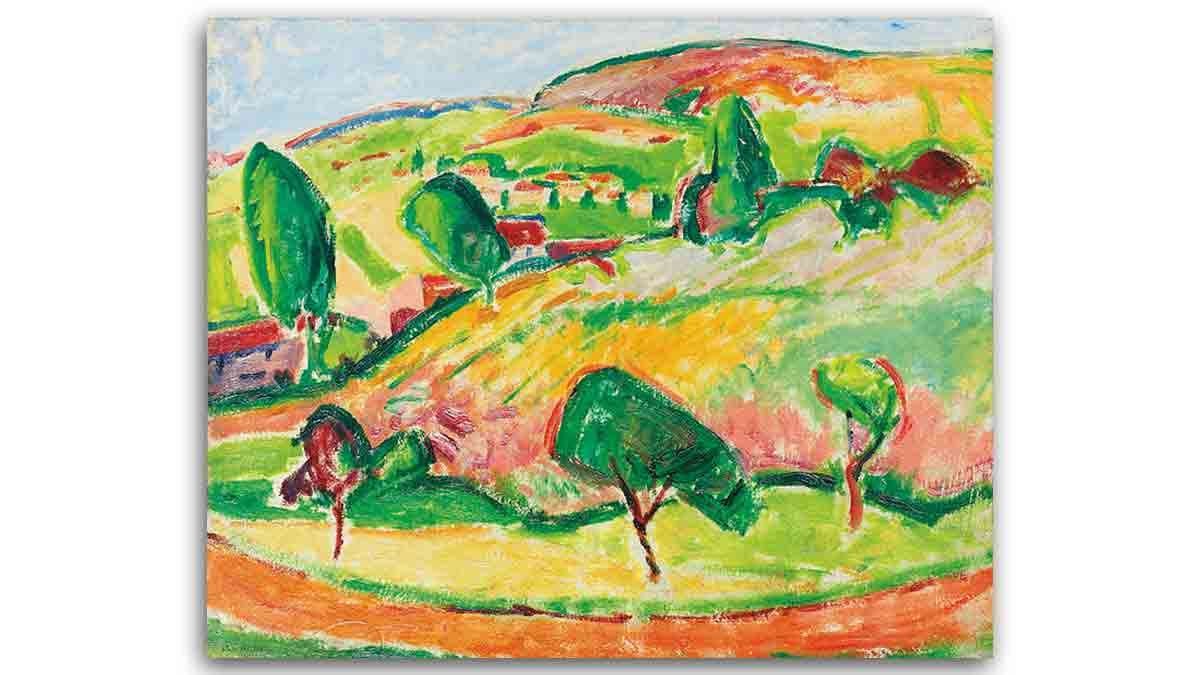

Featuring 65 paintings, archival objects, sculpture, prints and works on paper, Matisse and American Art juxtaposes 19 works by Matisse with 44 works by American artists who have felt his influence.

“The exhibition and accompanying catalog explore the pioneering roles that artists, critics, galleries and museums played in the establishment and dissemination of Matisse’s reputation,” said Montclair Museum of Art Director Lora S. Urbanelli.

“‘Matisse and American Art’ is the first exhibition to examine the master’s profound impact on the development of modern art in America from 1905 to the present,” said MAM Chief Curator Gail Stavitsky.” During this period, Matisse’s work has played a more wide-ranging role for both abstract and representative artists than previously understood. His oeuvre has provided a liberating model for varied explorations of vibrant color, strong fluid lines and clear compositional structures in the pursuit of artistic self-expression.”

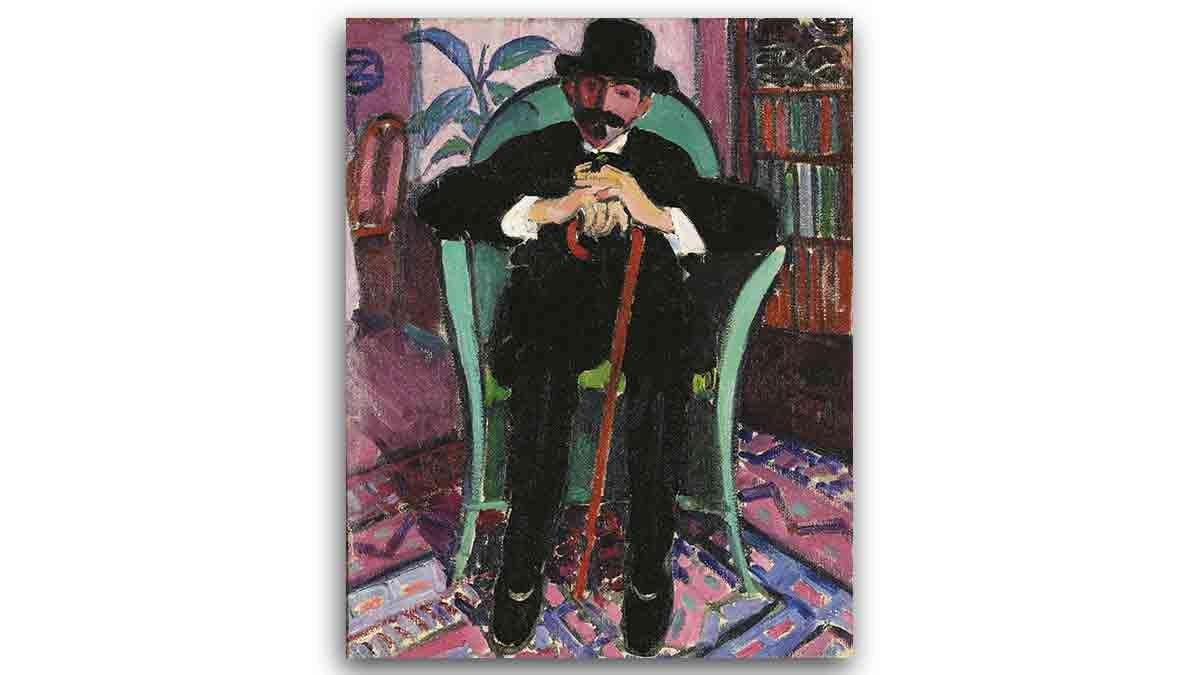

Matisse began developing an international following in 1908 as a result of the success of his public exhibitions. He developed close ties with American collectors: the Stein family, the Cone sisters and Dr. Albert Barnes, among them. His son, Pierre, immigrated to the U.S., establishing a gallery in New York, and soon painters adapted his color, line, composition and subject matter, whether in still lifes, landscapes, portraits or studio interiors. Milton Avery, Helen Frankenthaler, Sherrie Levine, Miriam Shapiro, Max Weber, William Zorach, Maurice Prendergast and Arthur Dove are just a few; Matisse’s postwar cutouts influenced Romare Bearden, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Motherwell and Judy Pfaff, among others.

Not only did Matisse impact American artists, they held sway over him, wrote independent scholar John Cauman in the exhibition catalog, when such American painters as Max Weber, Edward Steichen and Maurice Prendergast, among others, gravitated to Paris.

Matisse’s first patrons were the Steins—the expatriate Americans Leo, his sister Gertrude, and their brother Michael and his wife Sarah, an artist and student of Matisse. Soon, two sisters from Baltimore—Etta and Claribel Cone—joined them, also becoming smitten with the artist.

The Cones, like the Steins, were of a German-Jewish background, though the sisters did not move in the same bohemian, literary or artistic circles, and they preferred the more traditional of Matisse’s work: domestic subjects of modest size and scale. The Cone Collection would eventually assemble the largest private collection of Matisse sculpture in America.

For many, Matisse was an acquired taste. Some critiqued the lack of finish, non-traditional poses, spots of paint daubed on here and there. The work was likened to religious fanaticism, and some considered Matisse a poseur. Matisse was at the forefront of the Fauvists (wild beasts). When William Zorach went to visit Matisse he remarked on the drawings: “They had no meaning to me as Art as I then knew Art, but the feeling I got from them still clung to me and always will. It was the feeling of a bigger, deeper more simple and archaic world.”

Matisse and American Art includes some of his finest and well-known works, from his dancers and odalisques to “Interior at Nice” and “Pianist and Checker Players.”

Among Milton Avery’s affinities with Matisse were an emphasis on luminous color and surface pattern. Both artists averted dark subject matter (although Avery’s wife, Sally, claimed Matisse “was a hedonist and Milton was an ascetic.”) One had his subjects opening balcony doors onto Nice, the other opened windows onto the coast of Maine.

Robert De Niro Sr. (father of the American actor), a well-regarded painter in postwar New York City, referred to Matisse, along with Bonnard and Picasso, as one of his most admired painters. A photo of De Niro’s studio shows a bulletin board filled with reproduction Matisses. De Niro, too, painted seated women in brilliant color with bold brushstroke. He, too, was called an American Matisse, and an American Fauve.

Abstract Expressionist Helen Frankenthaler collected Matisse as well as a library of books about him. She was most influenced by his use of color. Among the titles of her works are “Celebrate H.M.,” “Homage to H.M.,” “Matisse Table” and “Madame Matisse,” in which she mimics his palette from an eponymous portrait, albeit in her signature abstract way. “One looks at Matisse for color, but I think I was affected by his line!” she wrote in 1985. “And the line melting with space and color.”

Sophie Matisse, the artist’s great granddaughter born in 1965, had long struggled with her legacy and name. Here we see the artwork that plays off her ancestor’s: her own version of a section of the “Dance” mural; her version of “Goldfish” but without the goldfish; a version of his “Conversation” without the two characters having the conversation. Her adaption of “The Piano Lesson” takes out the teenaged Pierre Matisse, who “did not like the music lessons that were forced upon him.” Removing these characters was “like clearing the decks of all the art world chatter about Matisse… one of many attempts to clear my artistic mind.”

The exhibition concludes with paintings by John Baldessari, Faith Ringgold, Tom Wesselman and Andy Warhol, who appropriated and adapted Matisse’s classic themes of the dance, the studio, the nude and the goldfish bowl. “Matisse… remains a guiding spirit for American artists of the 20th and 21st centuries,” said Stavitsky.

______________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.