Love sewn across generations

“I tapped into my grandmother’s energy and never looked back,” said designer Matin Fahim.

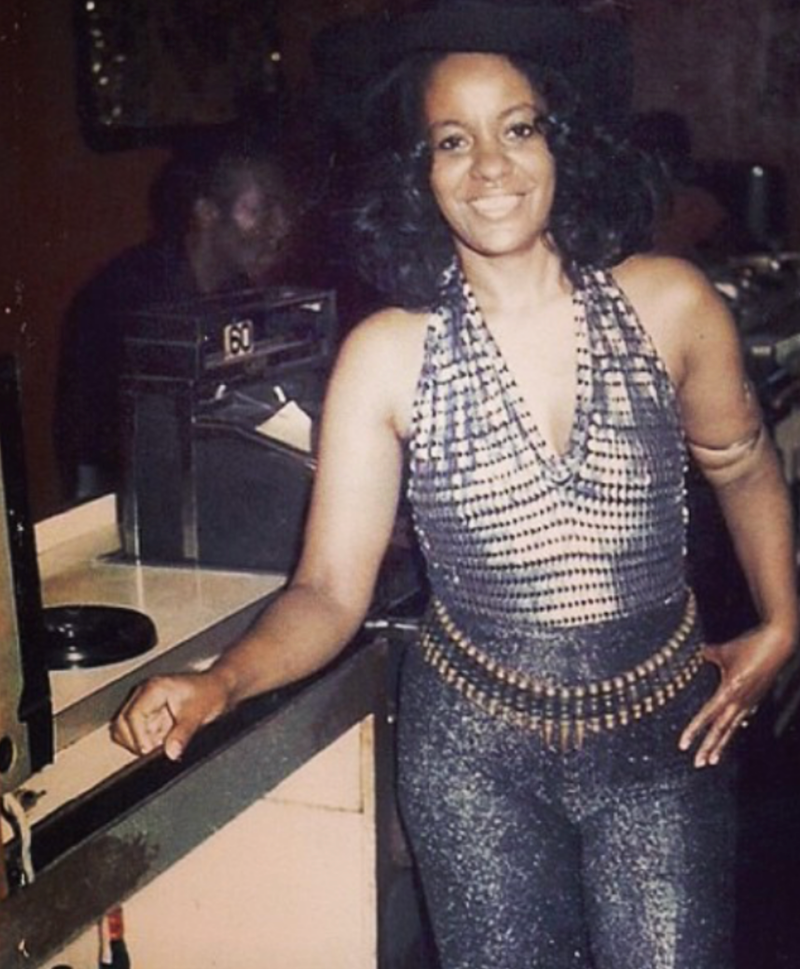

Matin Fahim, a Philadelphia-based fashion designer, at his workspace. (Love Now Media)

This story originally appeared on Love Now Media.

Lillian Smith was like many grandmothers, providing a refuge in difficult times and making even the mundane seem magical.

But Smith was more than a real-life fairy grandmother. She had a 9-to-5 and a side hustle. Smith made clothes on a rumbling industrial sewing machine: by-the-book uniforms for U.S. soldiers during the day, and glamorous outfits for neighborhood fashion shows at night. In between, she created hand puppets and cowboy outfits for her grandchildren.

Fashion designer Matin Fahim is one of her grandchildren. The married, father of three, was engulfed in memories of his grandmother on a summer day in 2013 when he was laid off from a job, and worrying about the future. By then, his grandmother had been deceased for 16 years and Fahim was staying at what had been her Southwest Philadelphia home. He walked down the creaky basement stairs and saw the black Singer sewing machine that his grandmother spent hours hunched over every night. He used to hand her the fabric she guided beneath a needle while she pumped a machine pedal on the floor.

“I tapped into my grandmother’s energy and never looked back,” said Fahim, 44, of Southwest Philadelphia. Soon after, he began teaching himself how to sew.

Fahim is a streetwear designer whose clothing line Threadcount might be described as a combination of his grandmother’s by-day utilitarian garments and nighttime street-fashion flare. He has turned his grandmother’s inspiration into a career and is hoping to inspire others, particularly those who, like him, found themselves on a path with a detour that led to incarceration.

Fahim served eight years in prison for armed robbery. He was released in 2006 and worked various jobs until he was laid off in 2012. When his unemployment was in its last weeks, Fahim walked down the basement steps, saw the sewing machine and remembered his grandmother’s entrepreneurial spirit.

“I totally got into clothes out of desperation. I couldn’t find a job and I was really trying to be self-sufficient,” Fahim said.

He started small, taking already-sewn garments and enhancing them. He added patches, changed the sleeves, and replaced the yoke in a shirt. Then, he began deconstructing garments and mixing and matching the pieces, combining them with new fabric.

Fahim sold his first garment, a shirt for $60. His most expensive sale, a coat made of a wool Aztec blanket, sold for $900. When he got jobs selling clothes at an Army Navy store or installing water meters, Fahim sewed in between his work hours. He also learned how to screenprint T-shirts. He was able to buy sewing machines and rent a warehouse space to sew and create. His clothes have been modeled by actors and musicians.

Fahim visited Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility (CFCF) and the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center (PICC) where he talked with young men and women about the fulfillment he got from creating. When several were released, Fahim taught them the basics of screen printing.

“I tell them about my experience in prison, coming home and then finding myself by making clothing,” said Fahim, “and I offered to teach them when they come home.”

For Fahim, designing and sewing is an outlet for the kind of expression and empowerment that comes from being able to transform yards of formless fabric into beautiful garments, or deconstruct already-sewn clothing and use the pieces to create something new.

“I love walking down the street and seeing someone wearing something that I made,” said Fahim, who sells his clothing at Gate 2-15, a shop on South Street, and on his Instagram feed. His fashions, a kind of outdoorsman chic, are rough-hewn and military, made from collage-like combinations of fabric.

Fahim plans to continue mentoring, a calling he describes as simply “doing what someone did for me.” As he builds his brand, he craves more time to devote to his clothing line. He believes his grandmother would be proud.

“I think she would be happy that someone is carrying the torch,” Fahim said, “and I think she would be doing this [clothing line] with me.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.