Designing cardboard hacks to modify wheelchairs

Temple University students create inexpensive adaptive designs for children with cerebral palsy.

-

Temple occupational therapy students work to design a new wheelchair tray for Eddie at the HMS School for Children with Cerebral Palsy. Working with cardboard, the students are able to create quick and inexpensive solutions customized to each child's needs. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Temple student Sarah Lustig takes notes while Kyle uses a keypad to describe the adornments he'd like on his soccer foot box. The customized attachment Lustig will design will allow Kyle to play wheehchair soccer. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Janice Barbour (left) tends to Carter, 7, who often gets his arms stuck behind the armrests on his wheelchair. Temple students Sarah Forsythe (right) and Ashley Bauer work to design attachments that will prevent that from happening. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Rachel Adler (left) and Nicole Maximowicz take measurments before designing a wheelchair tray that will protect Ana's communication device. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

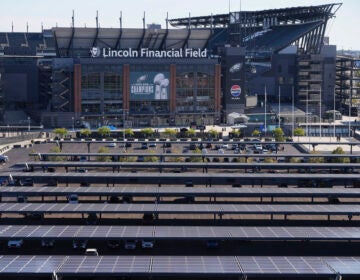

Russell Goldstein, of Adaptive Design of Greater Philadelphia, accompanies Temple students to the HMS School for Children with Cerebral Palsy. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Carter, a 7- year-old with severe cerebral palsy, has limited physical abilities. He spends most of his days at the HMS School for Children with Cerebral Palsy in West Philadelphia.

Carter often flails his arms uncontrollably, and then he has difficulty bringing them back to his sides again. When his arms get loose, he is uncomfortable and his anxiety increases. While his wheelchair is designed to give him as much range of motion as possible, his particular circumstance would benefit from a little less freedom.

Carter’s occupational therapist, Janice Barbour, hopes students from Temple University can help.

“The idea, I thought, was they could make something I could easily slide on his chair that would cocoon him in a certain position,” she said. “So he doesn’t get into that full outburst mode, and he can calm himself and stay engaged in the activity.”

Two dozen Temple students — most studying occupational therapy, with a smattering of architects — descended on the HMS school Thursday afternoon to inquire, brainstorm, and measure the students for customized adaptive tools. They are part of the Adaptive Design for Greater Philadelphia project, through the Institute on Disabilities at Temple.

A handful of students came up with a solution for Carter: a curved structure to be fitted to his wheelchair that would mimic a wingback chair — keep his shoulders and elbows a little more contained. The whole thing will be built out of sturdy cardboard planks, using tools most people have in their kitchen drawers.

The project was inspired by Alex Truesdell, an visionary educator of disabled children who, about two decades ago, came up with cheap and accessible methods of creating adaptive devices. Funded by the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, the Temple program roped together university and community partners to allow architects and occupational therapists to team up with disabled kids to identify, design, and build contraptions to make life easier.

Quickly made, economical gadgets

There are plenty of companies that can fabricate customized adaptive tools, but they are expensive and slow, said project manager Russell Goldstein. When working with kids, nimble is crucial — to be cheap and fast.

“They are growing,” said Goldstein. “By the time they put an order in, and it’s fulfilled, and it arrives, they have a month — maybe two if they are lucky — before they outgrow it. With this, if they outgrow it, we can refit it. It’s cardboard.”

One of the tricks to designing adaptive tools is figuring out exactly what’s needed, which isn’t easy if the patient can’t talk. Some children at HMS needed lightweight wheelchair trays that could be easily swapped out for different activities — one for communicating, one for playing, one for eating. A light shield for a monitor with eye gaze control would allow a partially paralyzed young woman to go outside on a sunny day and still communicate using her computer.

Another girl wanted her wheelchair outfitted with a cardboard foot. She likes to play wheelchair soccer, but does not have the leg strength to kick a ball, so she needed a cardboard foot fixed at ground level to dribble the ball.

Three other kids wanted cardboard feet on their wheelchairs, too, so they could all play together.

Rochelle Mendonca, an assistant professor of occupational therapy at Temple, urges her students to do this kind of work because it requires close listening, creative thinking, and collaborative design.

“We look at small, simple modifications that can be made that could change their lives completely, but they can’t afford it, or insurance won’t pay for it,” she said. “That one modification could be the reason they go outside the house, or go back to school, or buy their own groceries instead of sitting in the house all day.”

Mendonca admits she is all thumbs when it comes to fabricating things, but making adaptive tools from cardboard was remarkably easy — easier then assembling IKEA furniture.

“I’m not very good with IKEA furniture,” said Mendonca, who trained in these techniques before bringing them to her own students. “We were using steak knives, spoons, and paper bags from Whole Foods to use as edging. You could literally use a box from Amazon, and stuff you have in your house, and build a device for a child you are working with.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.