‘Lion and Leopard’ charts 19th century artistic clash centered at PAFA

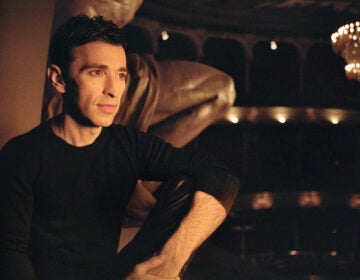

Nathaniel Popkin is the author of a new historical fiction novel "Lion and Leopard" which revolves around some of the artists who changed the course of American visual culture. (Nathaniel Hamilton for NewsWorks)

On opposite walls in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts historic building on Broad Street, two figures face off in an old, old fight.

On the right, one of the founders of PAFA, Charles Willson Peale, painted himself pulling back the curtain on the artifacts in his museum of natural science. On the left, Dr. Samuel Gross peers out of the gloom of a surgical theater, as painted by Thomas Eakins.

Each of these artists — in their own, sometimes opposing ways — changed the course of American visual culture.

“There was a great deal of friction, always,” said author Nathaniel Popkin. “It surrounded whether you could draw or paint from live nude models, which was not acceptable; how you learned — usually someone would be sent to Europe to copy master paintings and they would bring them back and learn from those. Then you’re in the process of semblance, of copying. All of a sudden you are working off of someone else’s cultural hegemony, not your own.”

Urban crowds vs. rational classical decorum

Peale and Eakins never faced off in person; they lived in different times. The fight for the soul of American art in Popkin’s first novel, “Lion and Leopard” (to be released Nov. 4) is a philosophical clash between Peale and John Lewis Krimmel, a German immigrant who quickly made a reputation as a genre painter before drowning in a Germantown mill pond at age 35.

“If you can imagine a kind of man who was known to be both direct and straightforward, and a dreamer at the same time,” said Popkin. “All of which is compressed into his scenes, which were capturing the urban world around him.”

Krimmel’s drawings and paintings often show city crowds. As his style matured, the once orderly and symmetric compositions started to get looser, more rowdy, as did his depiction of people’s behavior. The American republic he depicts is not the rational one championed by Peale.

Many of the characters in Popkin’s thoroughly researched historical fiction can be found hanging salon-style on the walls of PAFA. There is Peale (and again, as part of a portrait of George Washington, on whom Peale paints his own face); outsider artist Edward Hicks’ menagerie of animals witnessing William Penn sign a treaty with the Lenape tribe (an image created by artist Benjamin West that Hicks obsessively re-created over and over); and a scene by Krimmel, just a few feet from still-lifes by Peale’s sons, Rembrandt and Raphaelle.

Floating between these historical figures, Popkin invented a small band of hapless young men who try to pass themselves as art collectors and then, when that idea fails, as writers of an encyclopedia of American art. The guys are largely unaware of the sweep of history happening around them.

“They are completely clueless,” said Popkin. “That must be a reflection of me in some way. You really don’t know what the world is about. None of us do at any time. It only accretes in your consciousness little by little, what you’ve stepped into.”

Delving into historical mystery

The novel attempts to find out why, in 1821, Krimmel was elected to be president of the Society of American Artists and almost immediately dies.

“That Society [of American Artists] was a reaction to PAFA,” said Popkin. “There were always associations of artists who got annoyed with PAFA for the way it was not run by artists. He was voted president of one of them — a national association. A German immigrant — I’m not even sure how great his English was. And that year, he drowns.”

Popkin, who has written a nonfiction book about cities, is an editor of the popular Philadelphia urban blog, Hidden City. He is also a writer and history researcher for an ongoing documentary film project, “Philadelphia: The Great Experiment.”

Wearing these professional hats, Popkin is often asked to explain what happened in Philadelphia, then and now. In “Lion and Leopard,” he implies a line connecting age-old arguments about the stewardship of American culture and post-modern practices of reference and recontextualization.

“The notion of quoting, or relating, is wonderful. All creative people do it,” said Popkin, standing in front of fiberglass eviscerations of cartoon characters (by the contemporary artist KAWS) standing in front of an image of Old Testament hellfire by Benajmin West. “The idea that you are originally original is a great exaggeration. It’s tomfoolery. Everyone works off the conversation that’s been ongoing.”

As part of a book reading at PAFA on Wednesday, Popkin will guide a tour through the galleries, talking about the painters that appear in the novel.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.