Learning from ‘Zoned American’

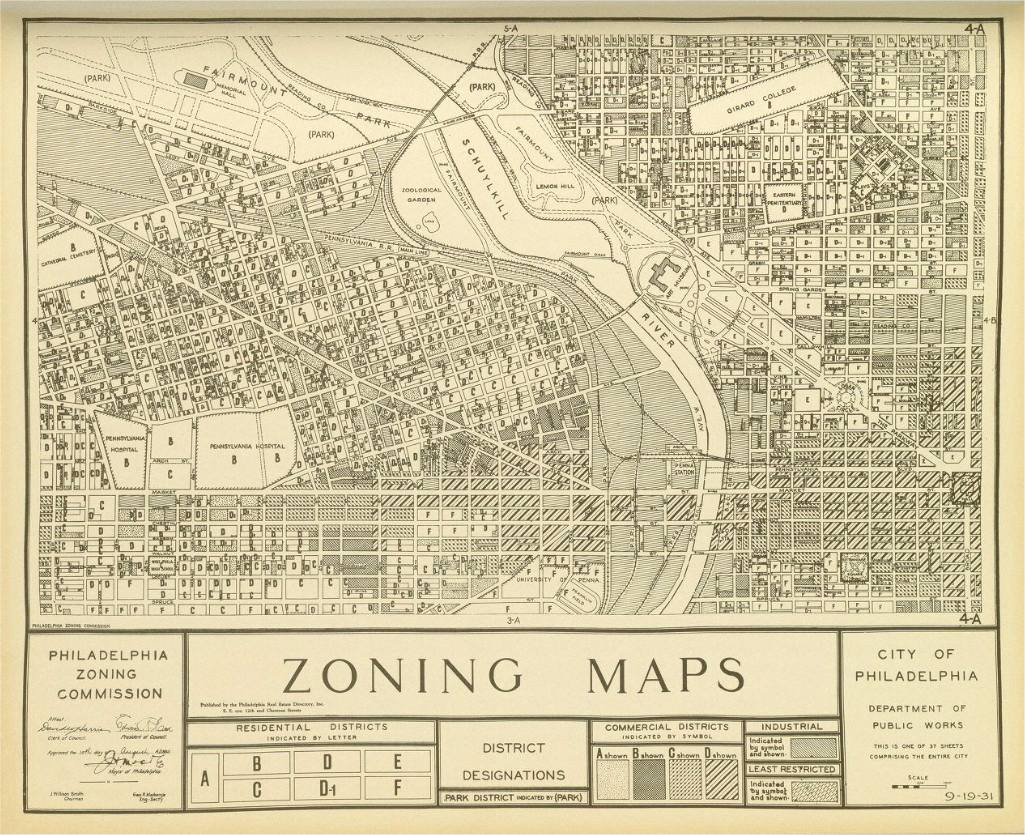

2016 marks the 100th anniversary of New York City’s zoning code, the first time such a comprehensive policy was implemented in America. Over the course of the 1920s, the trend swept the nation. By the end of that decade, fifty-six of the sixty-eight U.S. cities with populations over 100,000 were zoned.

But zoning remained a topic little studied outside professional circles for decades thereafter until, for a brief period starting in the late 1960s, there was a surge of attention in mass media and the popular press. For a short period, zoning received the attention it deserved as a monumental force shaping the character of many American communities—in large part due to civil rights protests over its exclusionary effects in newer suburbs.

Philadelphia lawyer Seymour Toll’s 1969 “Zoned American” was an influential part of the era’s reckoning with the subject. This West Philadelphia native, and current resident of Bryn Mawr, was inspired by his experiences in Philadelphia during the waning days of the Republican machine. As an intern with Edmund Bacon’s Citizens’ Council on City Planning he grew deeply interested in how cities worked and the hidden regulations and machinations that quietly crafted our built environment. The book is an in-depth history of the 1916 New York code, the progenitor of zoning regulations nationwide. The received history of zoning often frames it as a creation of Progressive-era good government planners. But “Zoned American” shows that the code was actually created as a weapon to defend the narrow self-interest of a small group of prestigious merchants.

Instead of civic-minded reformers, wealthy retailers based along Fifth Avenue were the advance guard of zoning in New York. Dubbed the Fifth Avenue Association, they believed their investments would be compromised by the northward advance of the garment industry and the hordes of foreign born workers that accompanied it. Their views are neatly summarized in a full page New York Times advertisement from March of 1916, which featured headlines like “The Factory Invasion of the Shopping District” and warned that “The evil is constantly increasing: it is growing more serious and difficult to handle. It needs instant action.”

The answer was a zoning code that sought to constrain height and density, to preserve the northern stretch of Fifth Avenue—and Manhattan more generally—for businesses that catered to the wealthy.

“Toll really clarified the origins of zoning,” says Benjamin Ross, author of this year’s “Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism” (which includes a dissection of the role zoning plays in incentivizing urban sprawl). “He’s really the person who sussed out that both the planning movement and the wealthy homeowners were junior partners and at the lead was the real estate industry and other elite business interests. There are a bunch of more recent books about how zoning was approved in New York, but I think it’s all based on what he dug up.”

Born in 1925, Toll was raised in West Philadelphia near the city line, close to 60th and Market. After serving in the infantry during World War 2 (he was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge) he went to Yale for his undergraduate degree. Toll dates his interest in urban planning to a summer internship with the Citizens’ Council on City Planning, a watchdog group created by Bacon and his reformer allies to keep the nascent City Planning Commission accountable.

Toll then attended Yale Law School, where he sought out zoning experts, and also spent a lot of time at the Architecture School. By the time he moved to New York City to clerk for a judge, his Philadelphia-bred interest in planning had already lead him to become a burgeoning expert on the esoteric subject.

“From 1951 to 1961 I was still living in New York and I got to know the physical setting and the early childhood of zoning,” says Toll, 91, from his home in Bala Cynwyd. “There was no extensive study of the origins of zoning and it interested me to find out where it came and how we got it, which is very much a Manhattan story. It’s not a book they’re going to make a movie out of, but it got the interest of a lot of lawyers and city planners.”

“Zoned American” was released by Grossman Publishers, the activist house that put out Ralph Nader’s “Unsafe At Any Speed” (after most publishers refused to touch the incendiary investigation). Despite the politics of his publisher, Toll says his interest was focused on the physical effects of zoning, not its social or political ramifications. That concern is clear from the photos of the built environment in the Lower and Midtown sections of Manhattan that stud Zoned American. Toll seems to be in the mold of the high-minded reformers who are often thought of as the progenitors of zoning, and the authorial voice in his book often seems to wince at the less than civic reasoning of the men who gave us zoning.

Regardless of Toll’s predilections his book expertly reveals the machinations of an influential segment of the business elite who were chiefly concerned with protecting their investments. The Fifth Avenue Association’s crusade against factories, height, immigrants and density, was the animating force behind the 1916 code, not careful urban planning. “What was natural was defined by a scheme of values promoted by a tiny interest group in the city to which a much larger community acquiesced,” Toll writes.

“There wasn’t some grand plan, zoning was taking whatever was there and freezing it,” says Stephen Smith, a former journalist who tweets under @MarketUrbanism and now works at Quantierra, a real estate brokerage and investment firm. (With Sandip Trivedi he recently mapped the buildings in Manhattan that could not be built under today’s zoning code for the New York Times.)

“People always told me zoning wasn’t planning, which I thought was ridiculous, its lines on a map, it looks like planning to me,” says Smith. “But Toll convinced me it wasn’t really planning, It was just reacting to whatever was already built. Rather than having planners go in and say this is what should be here and this is what should be there, they just [set parameters based on] whoever lived there or whatever was already built. It was just reacting to what these prominent property owners wanted.”

The year Toll moved back to Philadelphia, a massively more restrictive zoning code was being drafted in New York City. The zoning regulations of 1961 were draconian in the extreme, causing building permits to drop precipitously throughout the decade as Toll wrote his book. Meanwhile the exclusionary effect of zoning in the suburbs, where often only single family housing was allowed, was widely acknowledged too.

By the time Reagan took office, zoning ceased to be a live political issue in most places. Toll too had already ceased to pay attention to the issue.

“The book was published in 1969 and since that time I’ve had no involvement or interest in zoning or planning,” says Toll. “My attention has been drawn to other things. I was consumed by an interest in Americans in Paris in the 1920s. I was consumed by that and put aside everything else so I could get myself self-educated on the subject.”

His only other book is A Judge Uncommon: A Life of John Biggs, Jr, a biography of one of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s closest friends. Toll spent the rest of his career as a trial lawyer (he didn’t practice land use law) and a partner in a series of small firms. Long retired, he still writes occasionally for the Philadelphia Inquirer on his memories of World War 2 and the changing dress codes at Philadelphia law firms. “Zoned American” itself is hard to find, although most academic libraries have a copy and used editions can be had on Amazon.

“Reading it, I was like, wow, this is a classic. But I hadn’t heard of it before then,” says Smith, who had “Zoned American” recommended by a friend on New York City’s Planning Commission. “At the time zoning wasn’t a huge thing that people paid a ton of attention to. Then in the 1970s, there was a lot in the news about zoning at that time, exclusionary zoning, but people stopped talking about it in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Now it’s back in vogue again.”

With the importance of zoning again in the news, and its effects on the shape of our cities and suburbs poured over in a thousand think pieces, 2016 seems a good time to return to a book that reveals a different origin story of this fraught urban policy.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.