What is Hezbollah, the militia fighting Israel in Lebanon?

After trading fire across the Israel-Lebanon border for almost a year, this week Israel and Hezbollah have intensified the fighting.

A masked demonstrator waves a flag of Hezbollah during a demonstration supporting the Palestinians in Beirut on Oct. 20, 2023. (Joseph Eid/AFP via Getty Images)

Israeli airstrikes, artillery and tank fire into southern Lebanon this week led to the deadliest day for civilians and fighters of the militant group Hezbollah in up to four decades.

And on Wednesday, Hezbollah launched a ballistic missile at central Israel toward Tel Aviv, after days of ramping up rockets fired at northern Israel. The Israeli military says it intercepted the ballistic missile, calling it the first time a projectile weapon launched from Lebanon had reached central Israel.

Israel has shot down many of the rockets, and besides damage to several buildings, they have caused comparatively few serious casualties.

The two sides have been trading fire for almost a year now, most of it concentrated in Israel’s north and Lebanon’s south. But the Israeli air force has carried out an increasing number of sorties deep into Lebanese territory. The Israeli assault Monday killed nearly 500 people, according to Lebanon’s Health Ministry. Lebanese historian Charles Al-Hayek says that marked the country’s highest death toll from fighting in a single day since the 1982 Lebanon war.

And last week, Hezbollah accused Israel of blowing up thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies belonging to the militia, killing dozens and injuring thousands of people across Lebanon and in parts of Syria.

Here’s a brief history of Hezbollah, its origins and goals, and some background on its often elusive leader.

A militia born in civil war

To understand the rise and growth of Hezbollah, it’s important to appreciate the patchwork nature of the country in which it arose as a potent social and political force. Lebanon’s complex and fragile democracy distributes power along religious sectarian lines. The number of seats given to any particular group is proportional to its percentage of the population — the country’s largest populations being Christians, Sunni Muslims and Shia Muslims.

In 1975, increasingly fraught tensions among the groups, along with an influx of predominantly Sunni Palestinian refugees, plunged the country into a 15-year-long civil war. Amid the fighting, Israeli forces twice invaded and occupied the south of Lebanon in order to combat Palestinian guerrilla groups that had been launching attacks against Israel.

With the support of Iran (the region’s preeminent Shia power), Hezbollah, which began as a small Shia militia group during the war, emerged as the dominant force fighting against the Israeli occupation. In their efforts to expel the Israelis, the group became known for its use of extreme tactics, such as the infamous 1983 suicide bombing attack targeting barracks housing U.S. and French troops in Beirut, which killed 305. The group is sometimes credited with launching the modern suicide bombing era.

In 1985, Hezbollah — which means the “Party of God” in Arabic — released a manifesto, in which it pledged allegiance to the supreme leader of Iran, among the most senior Shia religious figures, and called for the destruction of Israel.

The United States designated Hezbollah a foreign terrorist organization in 1997 and several countries and organizations have followed suit. Some though, including the European Union, have employed that label specifically for the group’s military wing.

Hezbollah has tempered its Islamist political rhetoric somewhat in recent years, and in 2009 the group updated its manifesto to call for a “true democracy.” In the years since Lebanon’s civil war, Hezbollah has only grown as a regional power, and developed into a sophisticated political and military force — today its military wing and political wings constitute the bulk of its power.

Its political and military strength today

For more than 30 years, the political wing of Hezbollah has been an influential force in Lebanese politics. The group has maintained a steady presence of elected representatives in parliament, and has at times operated as the dominant party inside the country’s legislature. Members of Hezbollah have continually held executive cabinet positions.

Though Hezbollah is a Shia Islamist group, the party has forged alliances with individuals and groups affiliated with other sects. It also operates a wide range of social services in Lebanon, often carrying out particular civic functions that the Lebanese government does not in certain parts of the country — including at times the management of schools, hospitals and agricultural services.

“For Hezbollah, their priority has always been to preserve its military role as a substate actor within the state of Lebanon,” says Randa Slim, senior fellow at the Middle East Institute. “Politics has always been used as a means to maintain its independent military status.”

During the three decades since the end of the civil war, Hezbollah has greatly strengthened its military capabilities. Prior to the current conflict with Israel, it was widely considered to be the most well-armed and powerful non-state actor in the Levant region, with a stockpile of hundreds of thousands of missiles as well as 100,000 fighters. Though those figures have been the subject of debate among observers and analysts, Israeli officials have said publicly in recent days that much of its stockpile has been exhausted.

As a military power, Hezbollah was established in great part by Iran, and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in particular has for decades supplied the group with weapons and funding.

How Iran fits into the equation

Experts often describe Hezbollah as an extension or proxy of Iran, given the consistent supply of financial and military support the group has received over decades, and its stated allegiance to the Iranian supreme leader.

Senior Israeli officials, including former Defense Minister Benny Gantz, have often described the group as forming part of an Iranian “axis of evil.” Iran has taken to calling affiliated groups like Hezbollah, along with militias in Iraq and Syria, the Houthis in Yemen and Hamas in the Gaza Strip, its “axis of resistance.” Some of the groups are predominantly Shia, but some are Sunni.

“[Iran] trained the first cadre of Hezbollah fighters. They were the ones who helped put its organization and infrastructure together. They were the ones who provided it with weapons and financial support for a long time and still provide some,” said Slim, explaining that when it comes to issues of regional politics, Hezbollah’s actions are largely carried out in consultation with Iran, especially on matters relating to Israel, the U.S., or other Western powers.

But when it comes to domestic issues within Lebanon, Hezbollah is generally able to act autonomously, Slim says. “Over the years, the trust level between Hezbollah and Iran has become so high that when it comes to Lebanese domestic politics, Iran really lets Hezbollah play the leading role and does not get involved in their decision-making about intra-Lebanese politics.”

Hezbollah’s long-standing (and elusive) leader

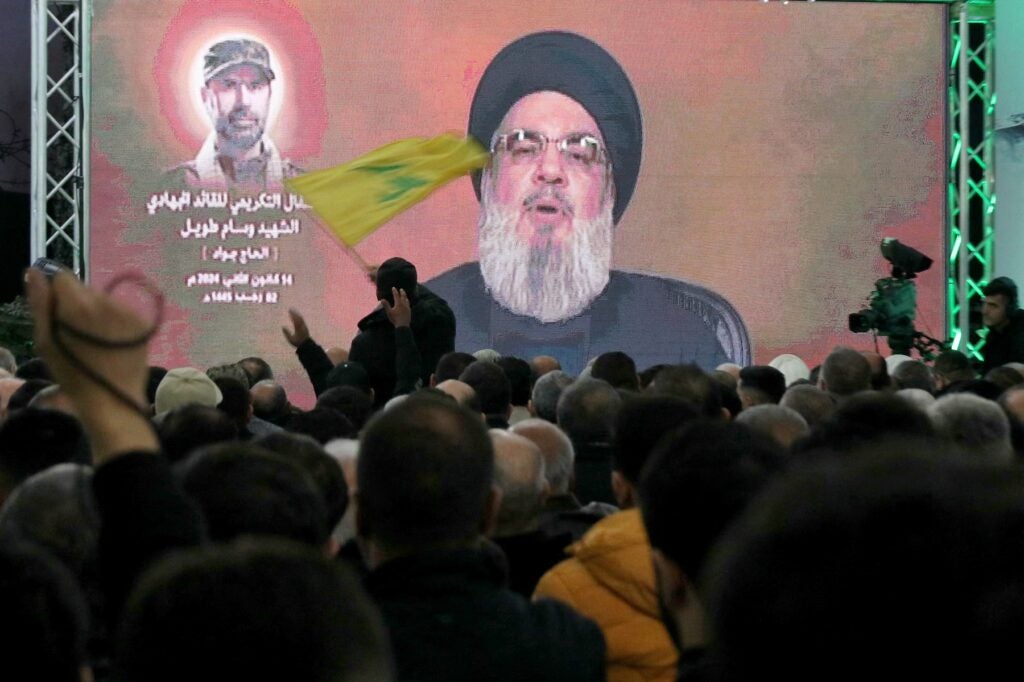

Hezbollah’s most senior leader is the group’s secretary general, 64-year-old Hassan Nasrallah. The Lebanese-born Shia Muslim cleric ascended to the top leadership position in 1992, when he was just 32.

During the 1990s, Nasrallah successfully led the group’s campaign against Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon, resulting in the eventual withdrawal in 2000. Today, many continue to view him as a dominant figure in resistance to Israel and Western influence in the region.

Though Nasrallah has never held a formal office in Lebanon, he is still one of the most powerful figures in Lebanese politics. He is credited with facilitating Hezbollah’s evolution from militia group to an influential and effective political force in Lebanon.

Today, Nasrallah is rarely seen in public for fear of being assassinated. Indeed, several of his senior deputies have been targeted by Israeli strikes in recent months. Still, he makes regular public speeches by video and is considered a compelling speaker.

With Lebanese hospitals still treating patients maimed by exploding pagers and walkie-talkies last week, the hundreds of others injured in strikes on Monday have prompted widespread fear and also anger among many Lebanese.

Nasrallah vowed retaliation for the pager and walkie-talkie explosions in a speech last week, while also admitting that the sophisticated assault represented a major blow to the group.

Almost 5,000 devices were detonated over several minutes last Tuesday and Wednesday, he said, and while many were in the possession of Hezbollah operatives or allies, they exploded without regard for who precisely was hurt — “with no problem with where or how they were killed,” as Nasrallah described it.

Nasrallah warned revenge was coming, but he was not prepared in his speech to offer details about when or how — but that if Israel wanted to return its citizens to northern communities close to the border, then last week’s explosions would make that much harder to achieve.

Jawad Rizkallah contributed reporting from Beirut.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.