‘This is a pox virus we know a lot about.’ Infectious disease experts in the region say monkeypox is familiar, preventable

The monkeypox outbreak may feel familiar to COVID-19, but infectious disease experts say we have the tools and knowledge to stop the spread.

Listen 3:14

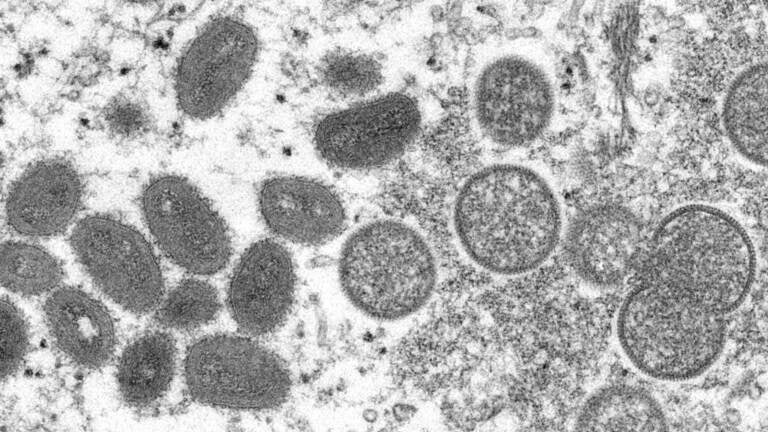

File photo: This 2003 electron microscope image made available by the CDC shows mature, oval-shaped monkeypox virus particles, left, and spherical immature particles, right. (Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Russell Regner/CDC via AP)

We’ve been living with COVID-19 for more than two years. And now, another concerning virus has reached the U.S. — 15 cases of monkeypox have been reported, with 250 confirmed cases worldwide.

On Monday, the World Health Organization’s Dr. Rosamund Lewis said health officials don’t know whether it will become a pandemic, but that it’s unlikely.

Still, public health experts want to know how the disease has spread across multiple continents over a relatively short period of time. The recent monkeypox outbreak is somewhat unusual, experts say, because the virus is not typically found outside of central and western Africa.

While infectious disease experts think it’s wise for the public to know about monkeypox, this outbreak should not necessarily trigger COVID déjà vu. Here’s why they say the U.S. is in a much better position to stop this rare disease from spreading widely.

How is monkeypox transmitted?

The virus that causes the disease — which is related to, but different from smallpox — is transmitted through close contact with broken skin, or through the eyes, nose, and mouth. Monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted disease, but it can spread through intimate contact.

One reason that cases of monkeypox in Africa may be on the rise is that many people are no longer vaccinated against smallpox, according to Dr. Stuart Isaacs, an infectious disease doctor and associate dean for animal research at University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

“There’s a growing population in Africa that’s never been vaccinated against smallpox, and therefore are not immune to monkeypox, and so there’s been more and more cases occurring in Africa, and then with world travel, over recent years, there’s been more cases of monkeypox popping up around the world,” Isaacs said.

Though recent cases of monkeypox have occurred mostly among men who have sex with men, it’s important for the public to understand that anyone can become infected with the virus, said Dr. David Cennimo, associate professor of medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

“It’s one of those things that we have to keep as potentially an interesting data point. But at this point, anybody with fever in a rash, I’d be thinking, ‘Could you have monkeypox?’”

Public health messaging must be transparent, while also avoiding discriminatory language, said Dr. Amita Gupta, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

“It’s very important to communicate, so that we can provide the information transparently, so people who may be at risk can be on the lookout,” she said. “But we also need to be very careful with how we present the information, and without stigma, without discrimination.”

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms typically arise about 12 days after exposure, but can present any time between four and 21 days. The virus can cause fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, and swollen lymph nodes. The most distinguishable symptom is a blistering rash.

Monkeypox usually causes mild illness for two to four weeks. However, some fatal cases have occurred in the past.

How is this outbreak different from others?

The experts say the new outbreak is noteworthy because of the number of cases across multiple continents at once over a relatively short time period. Health officials are still investigating the source or sources of the outbreak, and they still don’t know what the extent of it will be, the experts say.

“I wish I knew answers to where this came from, but I think that’s really the most pressing question; how this started and how it has spread to up to [23] countries at this point. That’s very perplexing, and unusual,” Isaacs said.

What interventions are there?

The smallpox vaccine offers protection against monkeypox, and can also be used post-exposure. Routine smallpox vaccinations were stopped in 1972, however, after the disease was eradicated.

“It’s the one and only disease in humans that we’ve actually managed to eradicate from the world. But we’ve kept smallpox vaccinations available in case it’s ever used as an agent of bioterrorism, or if it ever does reemerge. And of course, because of its cross-protection with monkeypox, we have access to a stockpile of it, as well for other indications,” Gupta said.

She said the monkeypox vaccine will not likely become routine again, because monkeypox isn’t expected to spread on a large scale.

“This is really an outbreak where we would only be considering vaccination for close contacts of cases,” Gupta said. “We don’t expect this to spread widely by any stretch; it’s really from close contact. So in terms of vaccination for the general public, we really don’t anticipate any need for that.”

Should the general public be concerned?

Health officials are prepared to handle monkeypox, Isaacs said.

“We should be interested, and looking for more information as scientists and epidemiologists get it. But I don’t think it needs the same alarm as the coronavirus pandemic, because we’re starting from a different point than we were with SARS-CoV-2,” he said. “This is a pox virus that we know a lot about. Scientists have been studying this virus for decades. We have vaccines, and we even have therapeutics.”

Because the nature of the spread is close contact, it’s also not nearly as contagious as COVID-19, Isaacs added.

Will these kinds of viruses emerge in the future?

While monkeypox may not be an immediate threat, the world will continue to encounter new, zoonotic viruses.

That’s, in part, due to climate change and humans encroaching on animals’ natural habitats, which also creates more opportunities for humans to interact with these new viruses, said Dr. Michael LeVasseur, assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University.

“This is just what we’ve been expecting as we encroach on other territories, as animals have to move territories, as ecosystems go up against the pressures of climate change, we’re going to see changes in the pathogens that are surrounding us,” he said.

Cennimo added that warming temperatures can reintroduce mosquitoes and other insect vectors that can present new vector-borne infections.

“Malaria was in the United States for all through the 17th and part of the 1800s. It wasn’t until the mosquitoes were really eradicated [that Malaria was eradicated],” he said. “But as warming happens, that can come back.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.