In York, college prep includes grappling with racial tension

Listen

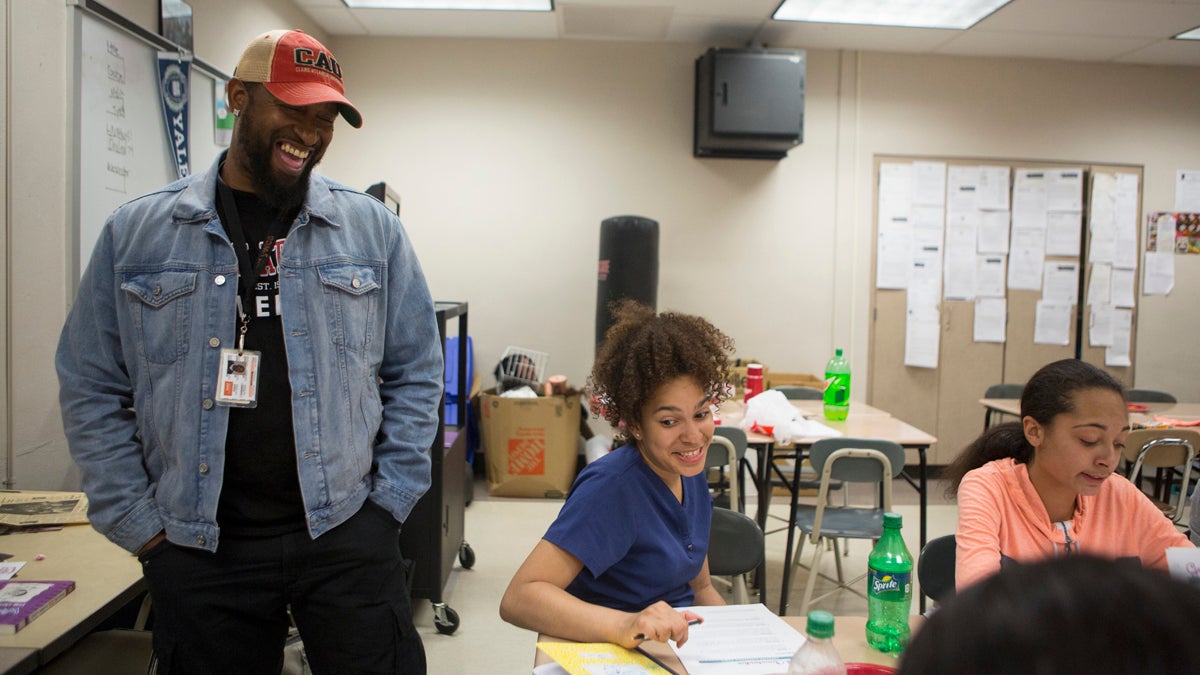

Mike Smith, left, grew up in York, and works with kids like Liz Herrera-Reynoso, 14, center, to deal with obstacles they face growing up here. As part of his job, Mike runs an after school college prep program, the York Temple Guard program and spends time counseling families on where to send their kids to high school. (Jessica Kourkounis/ For Keystone Crossroads)

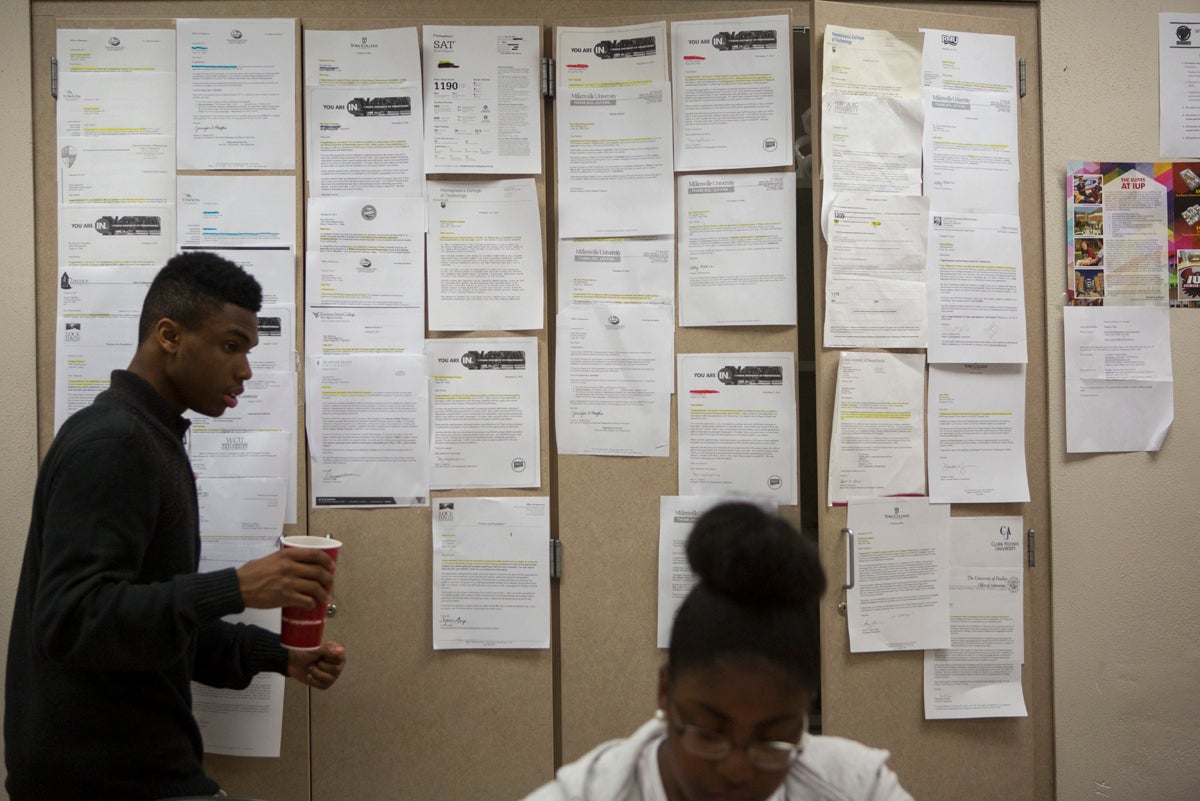

In a classroom at William Penn High school, college acceptance letters cover a bulletin board taking up almost an entire wall.

They’re for students in a guidance program aimed at overcoming obstacles kids face in a city like York.

York’s violent crime rate ranked eighth of more than 200 Pennsylvania law enforcement agencies reporting to the FBI in 2014.

Its poverty rate is 37 percent.

And at William Penn, the police department has a full substation on a heavily traveled hallway.

“These kids know more people who went to jail than college. That shouldn’t be,” says Mike Smith, who grew up in the city and now, at 49, runs the local YWCA’s Quantum Opportunities Program.

Over the past decade, all 150 teenagers who’ve completed the program have gone to college, according to Smith and YWCA director of programs Ruby Martin.

The program lets students bank up to $750 a year, held for them until they have college expenses, by getting good grades and being accountable for their time outside of school.

They also get a $50 check every time they make honor roll.

“Next year, I’m thinking about changing it to … this little thing they call A’s for J’s,” Smith says. “So A’s will get you a pair of Jordans.”

So what if everyone gets straight A’s?

“That’s a good problem,” Smith says laughing. “Maybe in a year or so, it might be a financial situation, because after a while, they’ll all gravitate to that higher standard.”

He says that’s what happened with the $50 bonus checks: program students are required to maintain a 2.0 GPA to stay in the program, but each group (up to 20 per class per year) averages 3.7 upon graduation.

The program also provides SAT prep, college tours, and other support. “All I want them to do is have options,” Smith says. “When you have options, you can figure out what you want to do.”

College acceptance letters hang on the wall in a classroom where kids from throughout York County attend an after school college prep program. (Jessica Kourkounis/For Keystone Crossroads)

College acceptance letters hang on the wall in a classroom where kids from throughout York County attend an after school college prep program. (Jessica Kourkounis/For Keystone Crossroads)

As part of his job, Smith talks with families about where to send their kids to high school.

For some, the York County School of Technology is a better academic option than their local public high school.

Others choose Tech so they can jump right into the workforce after graduating.

But Smith says parents have become more hesitant about their kids going to Tech due to something that happened there last fall.

A video was shot of York Tech students carrying a Trump sign through the hall while another shouted “white power” from the edge of the frame. The clip went viral.

“I’m trying to sell the education piece, regardless of that. Even when you go to college you’re not going to be able to control how people act,” Smith says.

Tech’s since hired a diversity coordinator and taken other steps in response to the incident.

For senior Delicia Marshall, who’s in Smith’s program, the viral video and surrounding events were the culmination of racial tension that had been building for months, something stronger than what she described as the typical undercurrent at Tech (the student body is 65 percent white versus 86 percent in the county overall).

Marshall stresses she’s glad she went to Tech.

“I learned a lot of things. Not only about myself, but about school and about how I can further my education,” she says. “It’s just a select few of the student body that if you don’t know how to deal with [them], it could break you.”

Marshall, who’s going to college this fall out of state, wasn’t among the dozens of students who left school early that day or maybe even stayed home the next because they felt unsafe.

This gets to one of the points Smith focuses on.

“I really condition them to take that on their back, and still don’t let it stop them,” Smith says. “’Cause you’re going to run into it here and there throughout life. It’s just part of it.”

For him, success goes beyond grades. He also mentors the kids on how to deal with stress, navigating the financial aid and college loan process, and other issues — including racial tension.

“At that age, I wish I woulda knew what I know now. So what I do is take what I know as a 49 year old man — coming up, being a minority, all my experiences — and I give it to them so that when they face it (some of the stuff that I give them they won’t even face it until later). But they’ll have the equipment to be able to make the right decisions.”

Editor’s note: This is the second story in the series, “Grappling with Racial Tension”, produced in conjunction with two episodes of our podcast Grapple.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.