In praise of double negatives

Congress has no business telling American businesses — or Americans, period — whom they should or shouldn’t boycott, which violates their First Amendment rights.

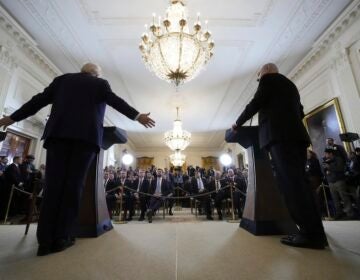

The debate over the boycott, diversity, and sanctions movement against Israel recently reached the floor of Congress. As a partial government shutdown over spending bills loomed, lawmakers added a proposed measure that would prevent American companies from participating in anti-Israel boycotts. (AP Photo/Amr Nabil, File)

In 1984, the eminent anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote a clever essay in defense of double negatives. I won’t explain why your high school English teacher told you not to use them (although I just used one myself). But in political dialogue, Geertz noted, double negatives are indispensable.

Geertz pointed to the anti-anti-Communists of the Cold War era, who denounced Joseph McCarthy’s hunt for “Reds” but weren’t Communists themselves. Or, to move closer to the present, many Americans are anti-anti-abortion: They oppose the campaign to restrict the procedure, but that doesn’t mean they want more people to have it.

The double negative “enables one to reject something without thereby committing oneself to what it rejects,” Geertz explained.

But in our rabidly polarized political era, double negatives have gone out of fashion. So when I write against campus restrictions on right-wing speakers, readers inevitably imagine that I’m right-wing myself. (For the record, I’m a liberal Democrat.)

If I question some university efforts to stop sexual violence, people think I’m diminishing or denying it.

And if I oppose the destruction of Confederate monuments, well, I must be a Confederate sympathizer.

So it’s kill or be killed, my way or the highway, heads I win and tails you lose. But we all lose, really, when we forsake the part of our humanity that lets us hold two different ideas at the same time. To borrow yet another double negative, you shouldn’t have to like everything that’s done against the things you don’t like. And I don’t want to live in a country where you can’t.

Consider the debate over the boycott, diversity, and sanctions movement against Israel, which recently reached the floor of Congress. As a partial government shutdown over spending bills loomed, lawmakers added a proposed measure that would prevent American companies from participating in anti-Israel boycotts.

Meanwhile, the Department of Education has reopened a previously dismissed case at Rutgers University, where Jewish students said that BDS supporters had created a “hostile environment” that placed the university in violation of federal anti-discrimination laws. In its other statements, the department has warned against vague campus speech restrictions aiming to protect racial and ethnic minorities. But BDS, apparently, is different: It’s clearly anti-Semitic, and Jews need protection from it.

Let me come clean: I loathe BDS. I acknowledge Israel’s violations of Palestinian human rights, but I’m appalled at the way the BDS movement singles out Israel — of all the nations in the world — for special condemnation. Supporters often reply that the United States gives a huge amount of aid to Israel, so it makes sense for Americans to target it. But we give huge sums to Egypt, too, and I haven’t seen campaigns to boycott that country for its persecution of Coptic Christians.

Nor are we asked to boycott Saudi Arabia for its woeful treatment of women, or Turkey for tyrannizing the Kurds. Among American allies, it’s Israel — and only Israel — that comes in for this treatment. That’s a double standard, for sure, and I’m sure that some of it is motivated by anti-Semitism.

But I’m also disgusted by the recent campaigns against BDS. Congress has no business telling American businesses — or Americans, period — whom they should or shouldn’t boycott, which violates their First Amendment rights. Already, more than 20 laws have been passed in states to restrict participation in BDS. The last thing we need is a federal anti-BDS measure, which will place even more limits on free speech.

Nor do I want the Department of Education sticking its nose into this matter. Although I do see strains of anti-Semitism in the BDS movement, the answer to bad speech is always better speech. And neither our universities nor the federal government should be determining which is which.

So I’m what Clifford Geertz would have called anti-anti-BDS: I’m against the movement, but I’m also against efforts to restrict it. Yet once this piece goes to press, I can already tell you how it will be received.

Supporters of BDS will assume that I wrote the piece simply to discredit them, even though I want their voices heard. And the anti-BDS crowd will interpret my criticism of their tactics as an endorsement of the boycott movement, although I explicitly denounced it.

You can’t have a healthy democracy on those terms. We’ve lost the ability to oppose something while also opposing campaigns against it. And most of us won’t say anything on behalf of things we don’t like. That might be the saddest double negative of all.

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches education and history at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author (with Emily Robertson) of “The Case for Contention: Teaching Controversial Issues in American Schools” (University of Chicago Press).

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.