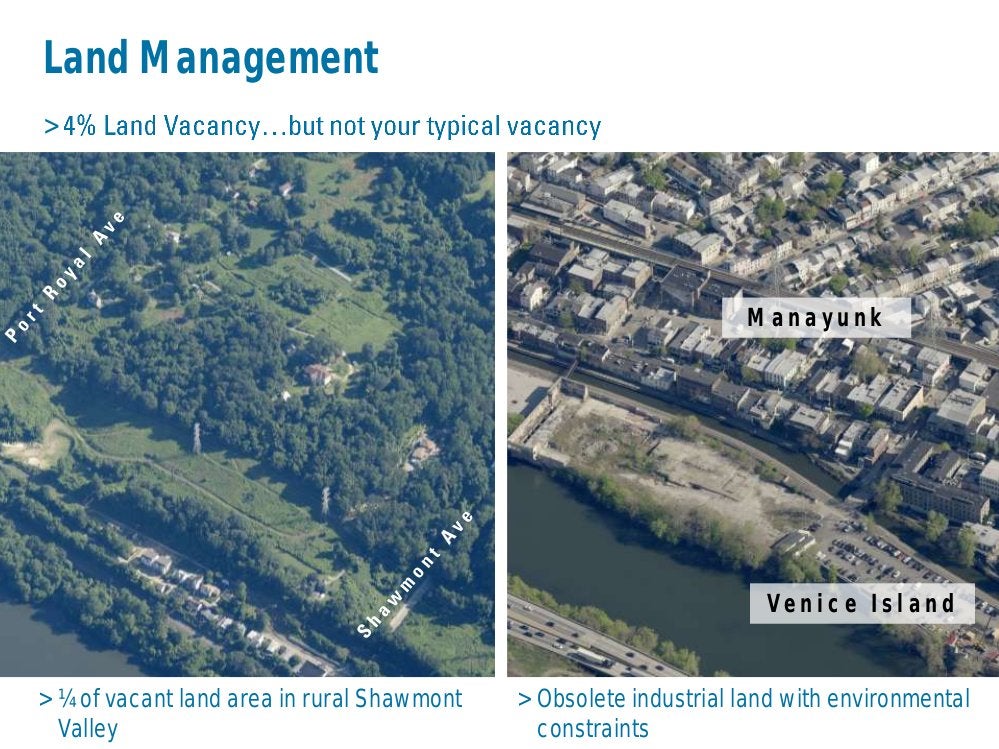

In Lower Northwest Philadelphia, a different kind of vacancy

In rural Shawmont Valley, the empty spaces aren’t abandoned houses or factories, but former agricultural land. The Lower Northwest District Plan will look at preservation. Other issues in the district that includes Manayunk and East Falls include protecting large homes on large parcels from tear-down, bolstering the East Falls riverfront commercial district and improving neighborhood connections to the Wissahickon Creek and Schuylkill River.

City and neighborhood leaders have been tackling the vacant land problem in many parts of the city, but the issue looks very different in the Lower Northwest District, City Planner Matt Wysong said.

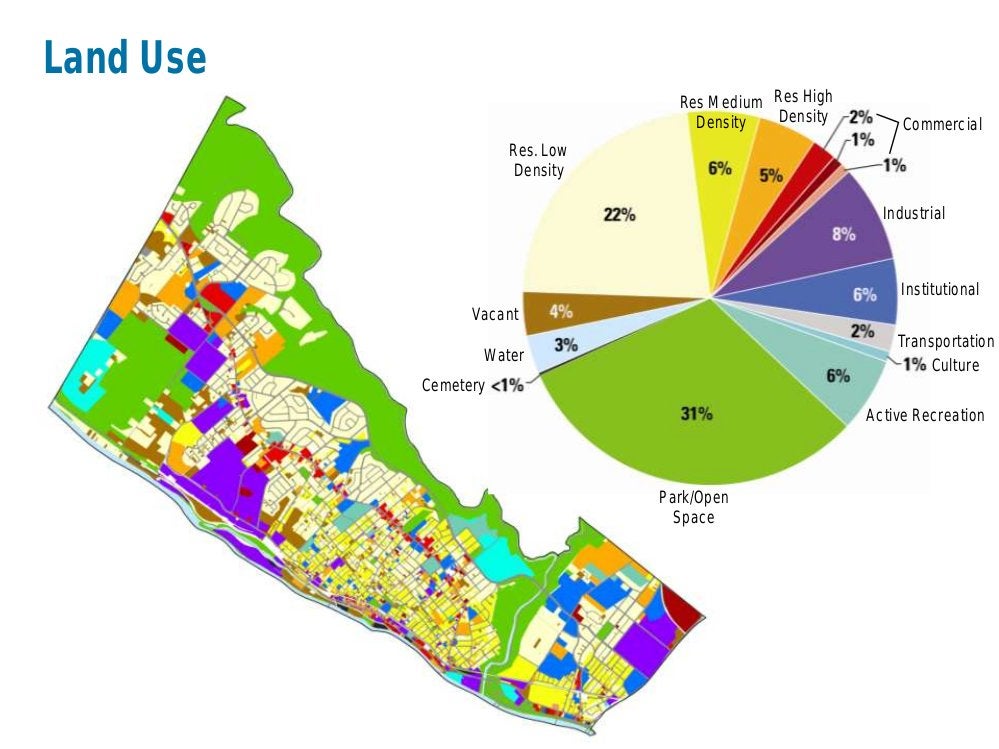

“A lot of the land we have classified as vacant – four percent of the district – is undeveloped greenfields, clustered in the Shawmont Valley area.”

The word “greenfield” is quite literal: Two large parcels – one owned by the Boyscouts of America, one in private hands – are former farms, that have now reverted to trees and grass.

They add to the rare, rural quality of life in this part of the city, and many residents are passionate about them remaining open space, Wysong said.

What’s kept development away so far isn’t any sort of preservation easement or agreement, but a lack of public utilities. Specifically, there are no sewer lines, he said. Homes can be built, but under circumstances much more common in say, Susquehanna County, than Philadelphia: With self-contained septic systems.

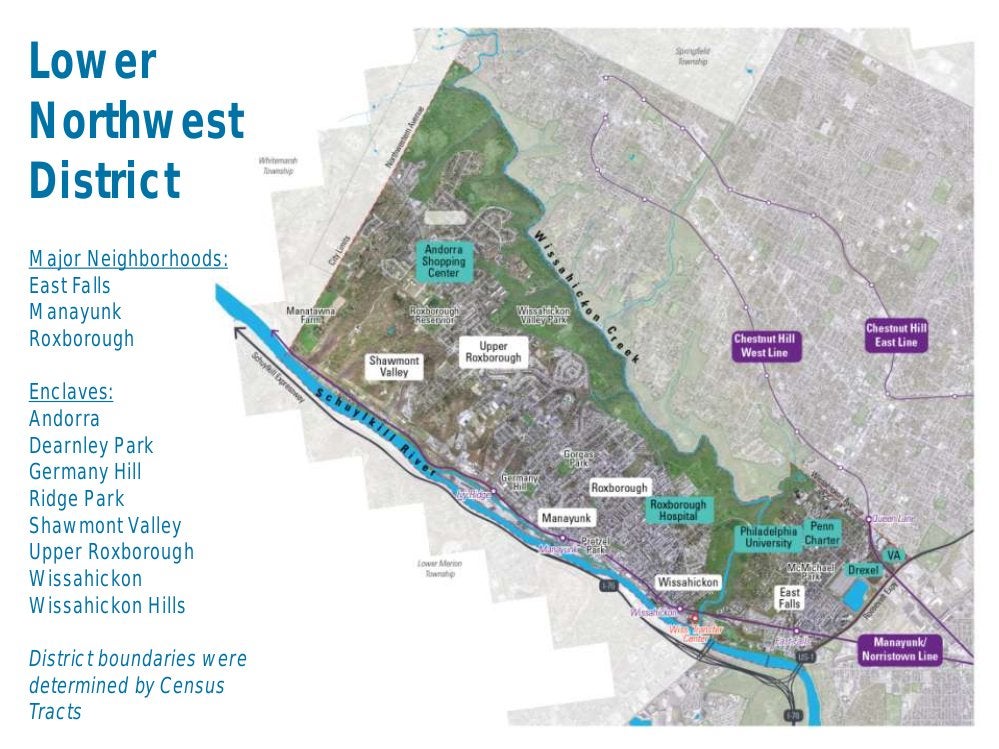

Wysong said there’s definitely development pressure elsewhere around the Lower Northwest District, which also includes Roxborough, Manayunk, East Falls and a host of enclaves: Andorra, Germany Hill, Ridge Park, Shawmont Valley, Upper Roxborough, Wissahickon and Wissahickon Hills.

Looking at L&I data shows that between 2006 and 2014, 4,984 new construction permits were issued in the city. While Lower Northwest residents comprise 3.3 percent of the total city population, 6.9 percent of the construction permits, 347 of them, were issued there, Wysong said.

The vast majority of these Lower Northwest permits were issued for residential development, with a clustering within Manayunk and Upper Roxborough.

“This data indicates an area of Philadelphia that is outpacing the citywide average of development, thus pointing to possible population growth and the emergence of “neighborhoods of choice” within the District,” Wysong explained in an email after this week’s planning commission meeting.

The Lower Northwest District Plan, like the eventual 18 other district plans, will be a comprehensive examination that applies the goals of the city-wide comprehensive plan to the Lower Northwest neighborhoods. City planning staff develop the plans through research and by talking with neighborhood residents and leaders in a series of meetings.

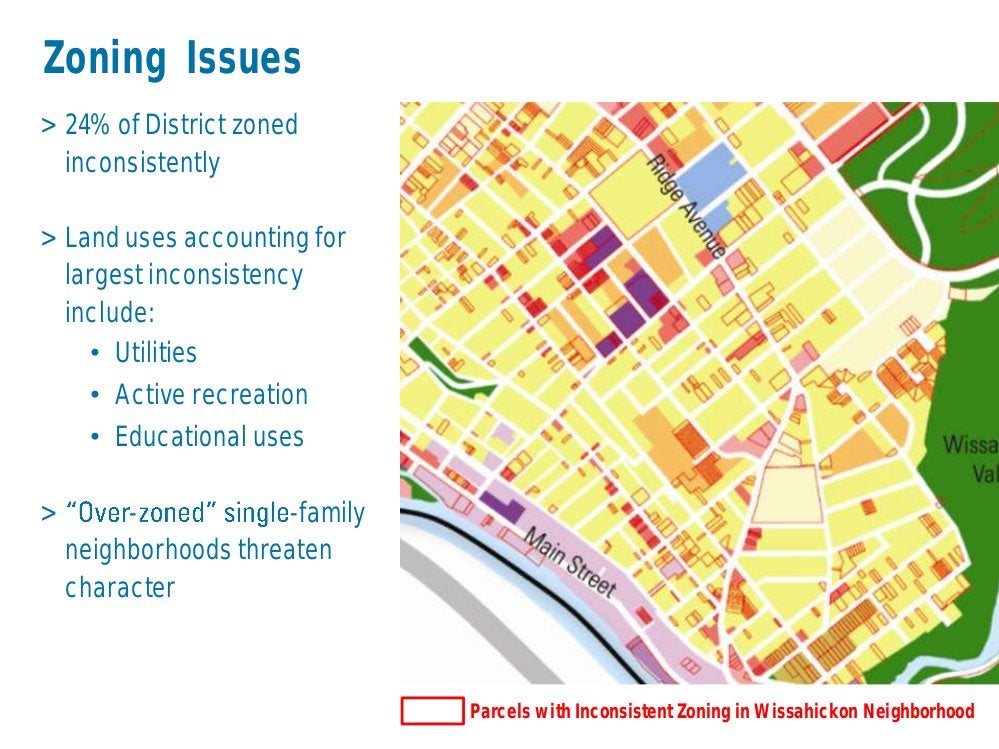

One development scenario was identified by Lower Northwest District residents at the first public input session as especially troubling: The tearing down of relatively large homes in Central Roxborough.

These homes, once occupied by mill owners, are not so big by mansion standards, Wysong said, “Not like the Victorian houses of West Philadelphia.”

Here, developers are after the large parcels the homes sit on – space enough for multiple smaller homes.

District plans covering portions of West Philadelphia and North Philadelphia have suggested zoning changes to protect mansions and other single family homes from being divided into multiple units.

Lower Northwest residents would prefer the homes remain as they are, Wysong said, but would consider subdivision a better alternative than the tear-downs.

While the recommendations for these homes vary by neighborhood, the goal is the same: Preserving characteristics that make the neighborhoods desirable and give them a distinct identity.

In Roxborough, some early zoning changes to address this issue have already been made, Wysong said. “The first test of them will be for 365 Green Lane, for which there’s a zoning hearing July 2.”

A developer has proposed tearing down the home, which sits on a corner, and replacing it with eight row homes with garages, he said. Learn more from Newsworks, here.

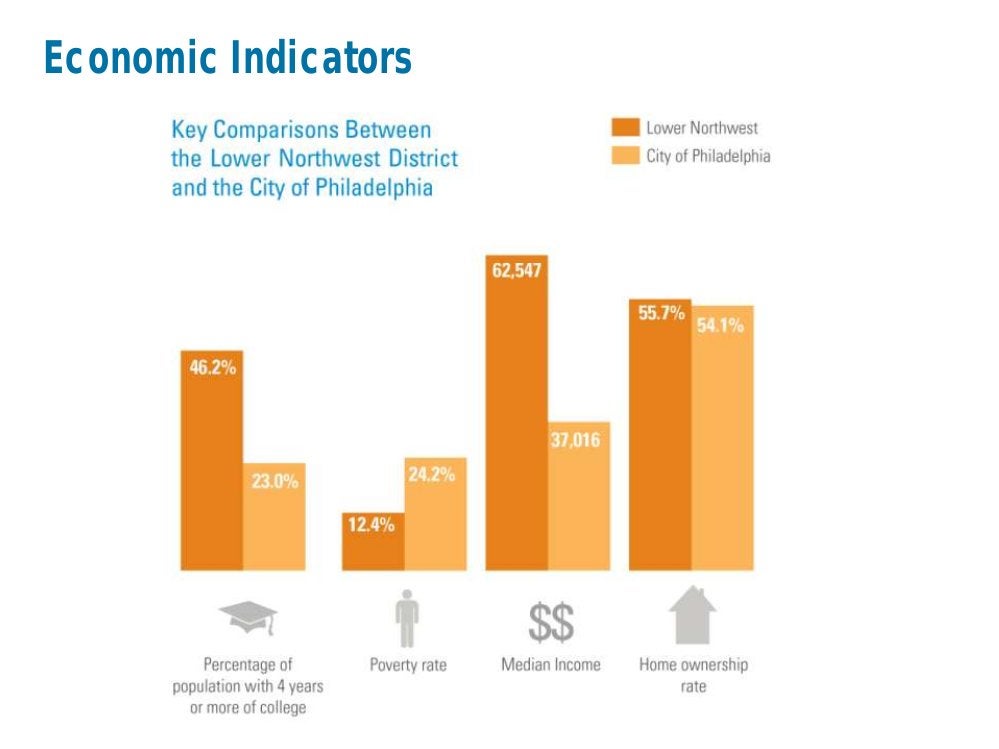

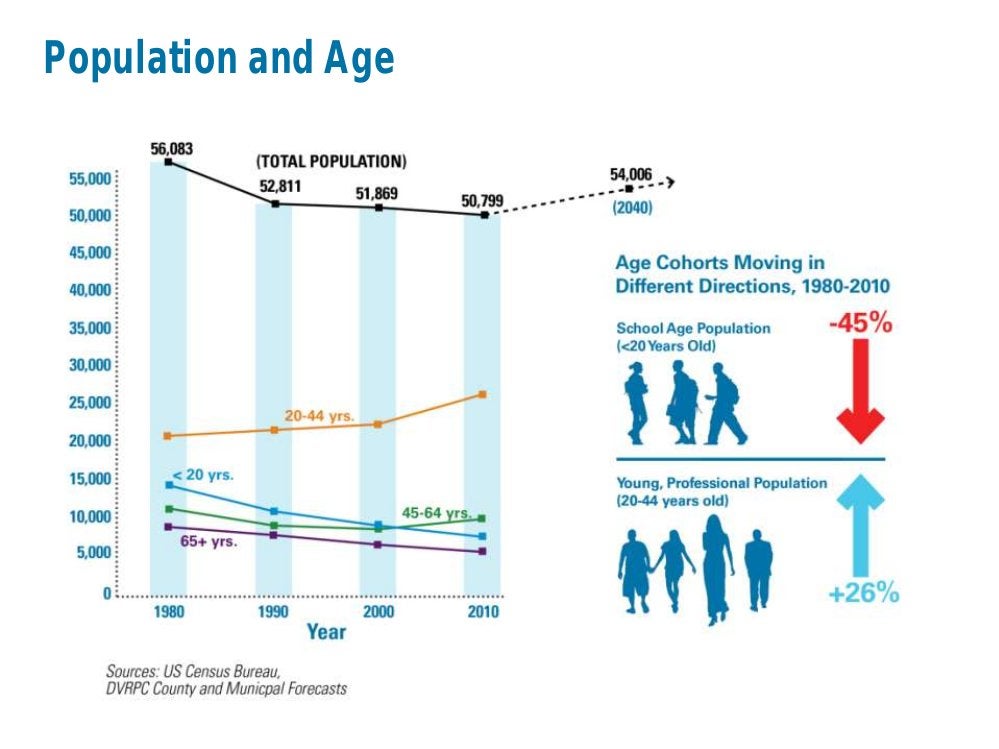

The 50,799 residents of this district are fairly well-off, with both median income and the levels of education double the city-wide averages, and the poverty rate is half that of the city average. The population has been stable for the past three decades, but is down from a high of about 56,000. The district is expected to grow by about 3,000 new residents through 2040.

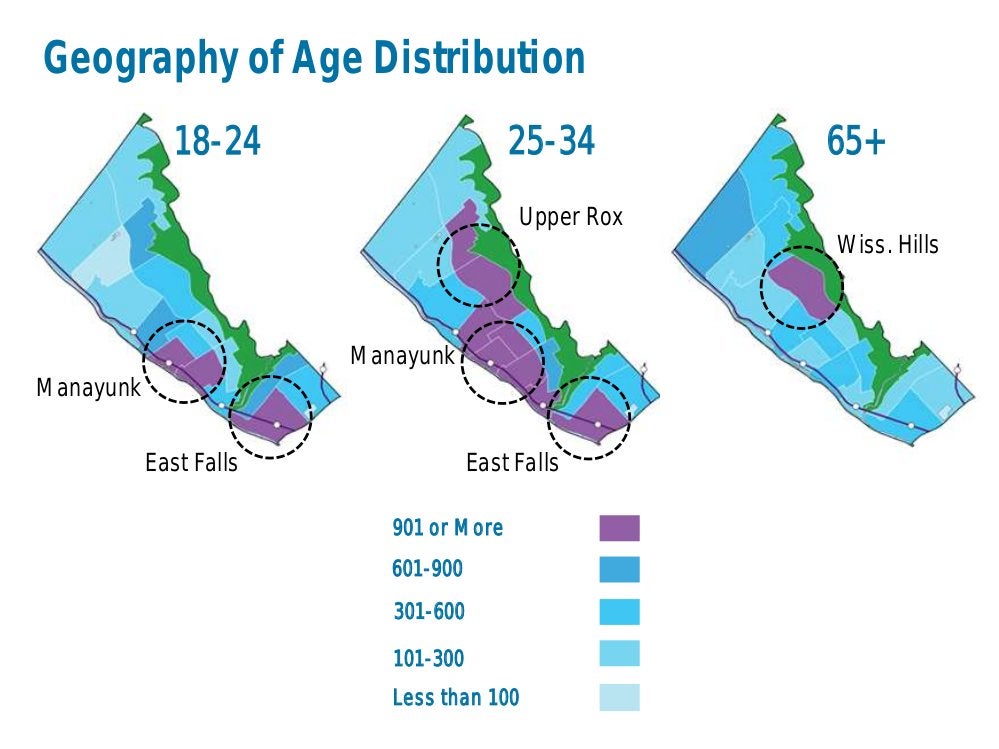

Wysong noted a trend in the numbers for commissioners: There was a 45 percent drop in the number of school-age children between 1980 and 2010, but a 26 percent increase in young professionals, ages 20 to 44.

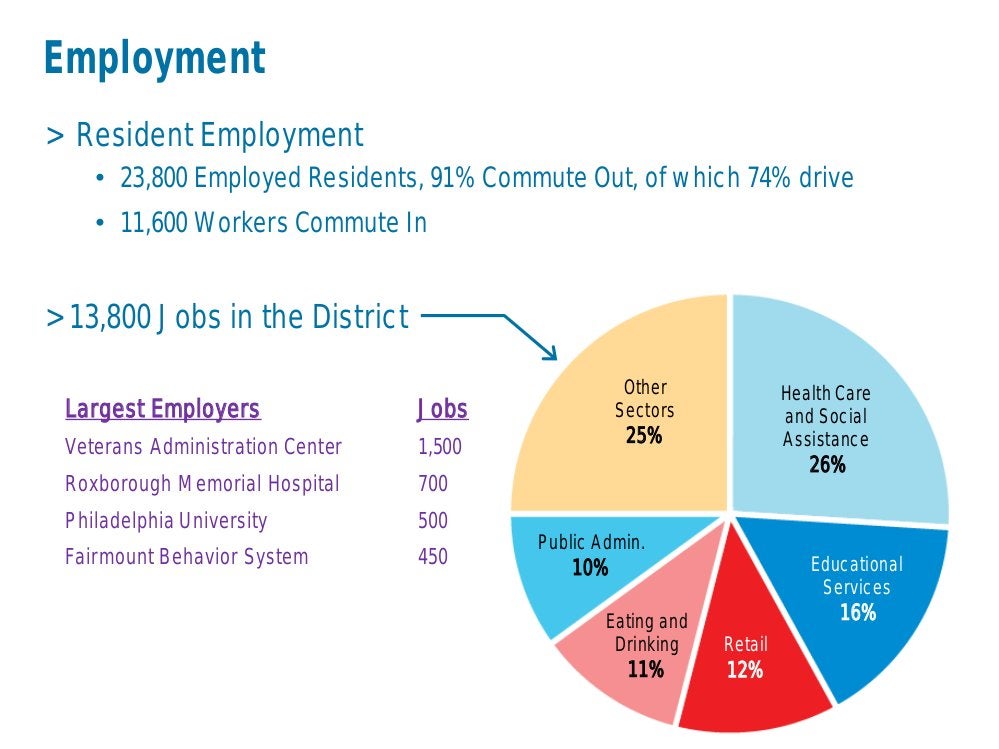

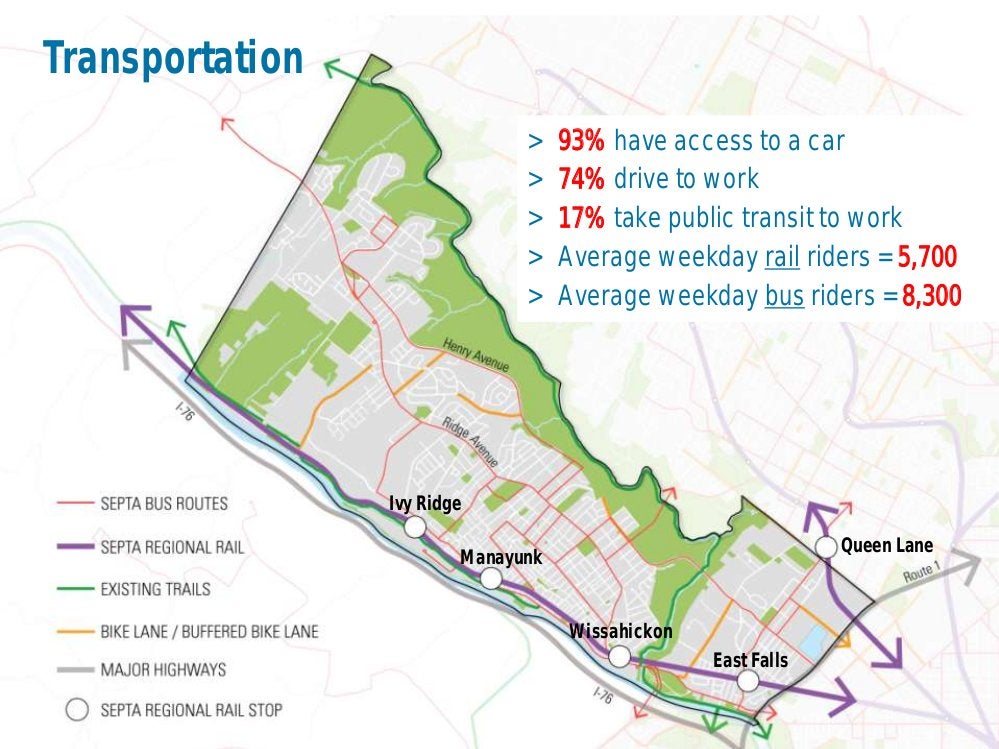

The district boasts several major employers, including the Veteran’s Administration and Roxborough Memorial Hospital. But the majority of the district’s 23,800 working residents – 91 percent – commute outside the district for work. With the exception of those who live near one of the public transit stops, most drive.

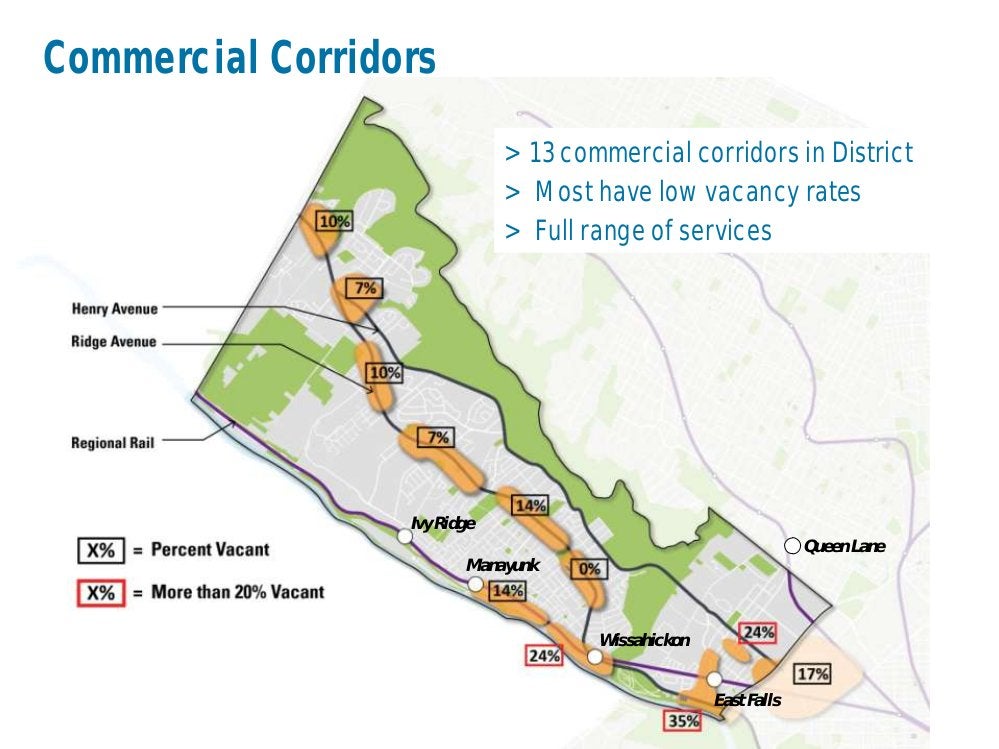

Just as there aren’t many vacant houses in the district, the commercial real estate vacancy rate in the district’s 13 commercial areas are also healthy, with most ranging between 5 and 15 percent.

But some commercial areas struggle a bit, including the East Falls Riverfront District, where vacancies range between 25 and 30 percent, Wysong said.

In a discussion after the meeting, Wysong explained the issue by comparing this area with main street Manayunk. In Manayunk, there are many residences near the business district, and access is also relatively easy for those who live on the hills away from the district. But the great majority of East Falls residents are separated from that commercial area by train tracks. They largely shop elsewhere, and the businesses are more dependent on people coming from elsewhere.

The district plan will look for a solution, a large part of which will likely be encouraging residential development on the same side of the tracks as where the business sit, he said.

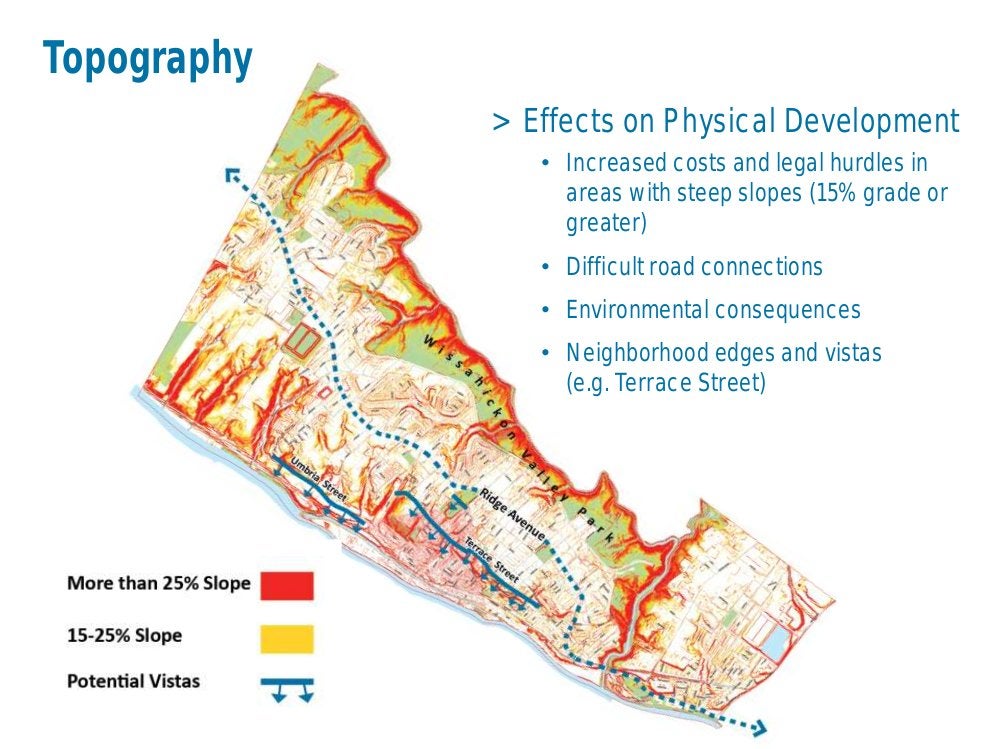

Speaking of the district’s hilly terrain, the topography has “lots of effects on physical development,” Wysong said. Steep slopes impact walkability, add to building costs, and can contribute to erosion and flooding. “On a positive note, there are great vistas,” he said.

The district boasts a lot of parkland, much of it along two bodies of water: The Wissahickon Creek and The Schuylkill River. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to get from every neighborhood to the river. Improving those connections, and filling in some trail gaps, will also be a chief goal of the district plan, Wysong said.

To learn more, click through the slides from Wysong’s planning commission presentation or watch a video of it below, or learn about the Lower Northwest and other district plans at the Philadelphia2035 website.

Want to contribute? The second public input session for Lower Northwest will be held 7 p.m. Thursday, June 26 at the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education, 8480 Hagys Mill Road. Doors open at 6:30, and there’s free parking available.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.