Ideas Worth Stealing: Move Pennsylvania’s Capital out of Harrisburg and back to Philadelphia (or to Pittsburgh!)

Would Pennsylvania’s state government be less corrupt if the capital was relocated from Harrisburg to Philadelphia or Pittsburgh? Researchers Dr. Filipe Campante and Dr. Quoc-Anh Do found that state capitals that are isolated from main population centers are far more likely to be corrupt. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Harrisburg has a corruption problem.

Harrisburg has a corruption problem. The current trial against former mayor Stephen Reed, who is fighting 449 counts of theft, bribery and racketeering that he accumulated during his nearly three decades of public service, is only the latest example of a public official misbehaving in our state’s capital.

Over the past four decades, 40 state legislators or aides — including three former House speakers and a former Senate president pro tempore — have been convicted of corruption charges. In 2015, former Treasurer Rob McCord pleaded guilty to two counts of extortion; more recently, Attorney General Kathleen Kane lost her law license and is currently fighting perjury charges for her alleged leaking of secret grand jury documents. Corruption in Harrisburg is so bad that bronze plaques noting corruption charges now hang from four portraits in the state capitol building.

No surprise, then that Pennsylvania has the dubious distinction of being tied as the sixth most corrupt state in the country, having received an “F” grade from the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit news organization.

Given the endemic corruption in Harrisburg, it’s worth asking: Is it time to move the state capital to Philadelphia or Pittsburgh? Could we cut out the rotten core of our state government simply by relocating it?

Isolation Breeds Corruption

It’s an idea with research behind it. In 2014, Dr. Filipe Campante and Dr. Quoc-Anh Do, of Harvard’s Kennedy School and the Paris Institute of Political Studies, respectively, published a paper in the American Economic Review with a startling conclusion: state capitals that are isolated from main population centers are far more likely to be corrupt.

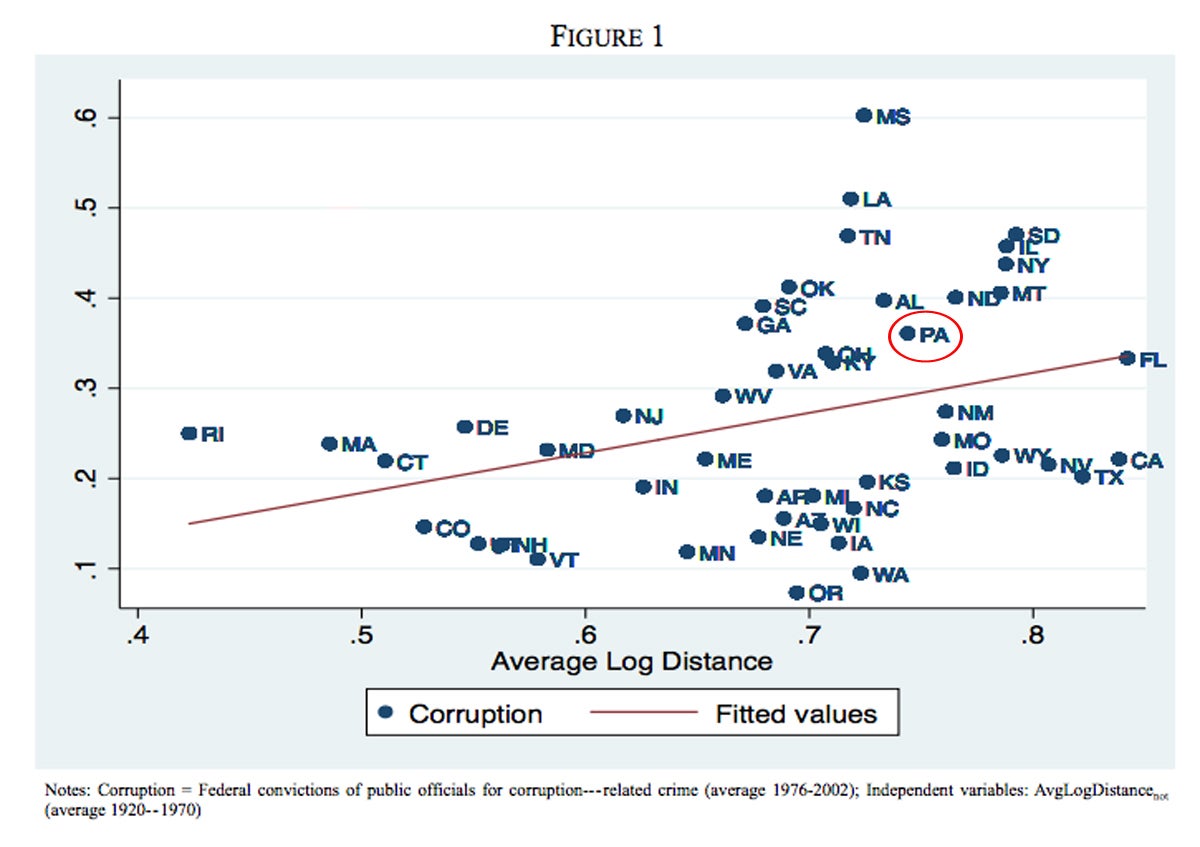

Campante and Do’s research combined average number of federal corruption convictions from 1976 to 2002 with the average distance state residents lived from the state capital to show that there was “substantial evidence of a link between isolated capital cities and greater levels of corruption across US states.”

Here’s a chart from their paper — corruption is charted on the vertical scale, while the average resident’s distance to the capital is the horizontal. Pennsylvania is toward the top right, just above the red line.

(Source: “Isolated Capital Cities, Accountability and Corruption: Evidence from U.S. States,” American Economic Review, 2014)

The reason that far-flung capitals are so filthy, the co-authors write, is reduced accountability. Media outlets, which tend to be based in major cities, generally focus on their own backyards, while citizens pay less attention to what’s happening in a remote capital city. Voter turnout in state elections is actually lower when the capital is in an isolated location. (According to a study by the University of Florida’s United States Elections Project, only 36.5 percent of eligible Pennsylvanians voted in the 2014 midterm, placing us 32nd in the country). The result: bribery, corruption, and extortion are far more likely to occur when nobody is watching.

In addition to Harrisburg, the paper highlights other legendarily corrupt state capitals, like Albany in New York and Springfield in Illinois, which you can see in the chart (they’re above and to the right of Pennsylvania). The authors note that the results sit oddly next to the original reason some states moved their capitals away from major cities: to avoid corruption. (According to the Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee, our state capital, which was originally located in Philadelphia, moved to Lancaster in 1799 for “reasons ranging from disease to population growth;” it was moved again, to Harrisburg, for free land in 1812.)

Campante and Do ultimately conclude that “isolated capital cities require extra vigilance, to counteract their tendency towards reduced accountability. Put simply, watchdogs need to bark louder when there is a higher chance that people are not paying much attention.”

If You Can’t Beat Them, Leave

Trying to get people to pay more attention to what’s happening in Harrisburg is certainly one solution, but despite constant media coverage of the state’s recent budget crisis, Pennsylvania citizens never moved to express any type of collective outrage toward the inaction. So, if the media can’t motivate citizens to act against a remote capital, why not move it to one of the state’s major cities, Philadelphia or Pittsburgh?

Both cities, after all, have two daily newspapers, as well as a variety of magazines, alt-weeklies, radio stations, and TV outlets, so there are plenty of watchdogs. There are also a lot more local people who would be paying attention — metro Philadelphia has more than 6 million residents and metro Pittsburgh has 2.4 million. Harrisburg has only 560,000.

Granted: some Philadelphia politicians make the floor of a SEPTA bus after the Mummers Parade look pristine. U.S. Congressman Chaka Fattah is currently facing federal charges of racketeering, while city residents voted in April to abolish the Philadelphia Traffic Court in the wake of a ticket-fixing scandal. Pittsburgh is a bit better, but let’s not forget that the city’s former police chief, Nate Harper, recently served more than a year in prison for creating and drawing on an unauthorized slush fund.

Even so, given that Pennsylvania has spent two centuries failing to quite make this whole “Harrisburg capital experiment” work, maybe it’s time to try something new. Good luck, though, convincing a new city to take on the responsibility of being the capital.

“I don’t want it!” said Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto, laughing, when presented with the idea. “I like having a buffer between state politics and our own local government called the Allegheny Mountains. It’s a different world there from Pittsburgh — Harrisburg politics may be more akin to the eastern part of the state, around Philadelphia.”

“Pittsburgh politics may be rough and tumble, and in different cycles there sometimes may be some corruption that occurs, but we’re able to quickly put it out,” he added. “I think the [Harrisburg] culture would actually hurt [us].”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.