Hurricane season may be off to a slow start, but experts say major storms are ahead in the region

One year after remnants of Ida brought devastating floods to the region, no major tropical storms have hit the Delaware Valley. But experts still expect a busy season.

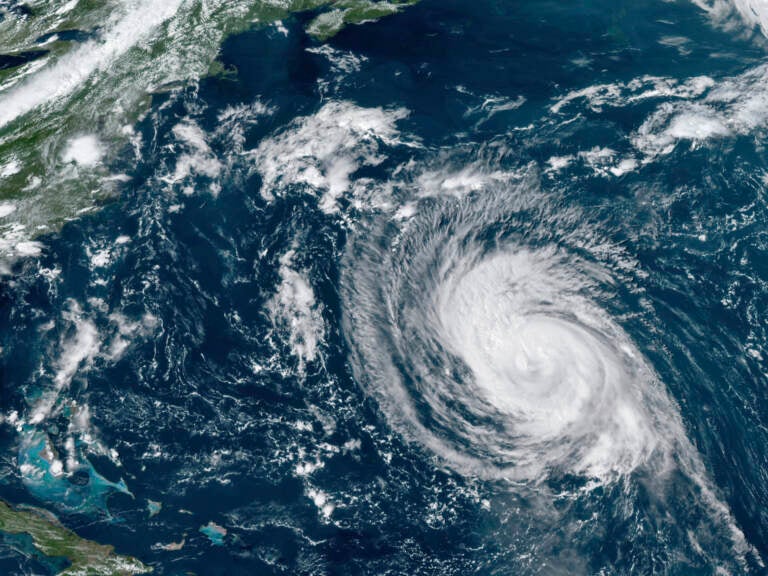

File photo: This satellite image taken on Sept. 8, 2021, shows Hurricane Larry in the Atlantic Ocean. (NOAA via AP)

One year after remnants of Hurricane Ida brought drenching downpours, devastating floods and tornadoes to the region, the Atlantic Coast has yet to see any significant tropical storm activity. This despite dire warnings by both NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center and Colorado State University that 2022 would be an above average Atlantic Hurricane season.

But experts say the worst may be yet to come.

“We’ve really been quite lucky,” said Dan Leathers, Delaware’s state climatologist and a professor at the University of Delaware. “But there are still pretty good reasons to think that as we get into the peak of the hurricane season, things could become a bit more active.”

NOAA has forecasted 14 to 21 named storms between June 1 and November 30, with 6 to 10 major hurricanes. Both forecasters adjusted their predictions in early August, but still say this year will be busy. So far, only three named tropical storms have formed in the Atlantic, none of which were major hurricanes.

Leathers says La Niña conditions in the Pacific Ocean typically create a busier Atlantic Hurricane season. Additionally, he said high sea surface temperatures, weak trade winds, and an active storm system in the western part of Africa contributed to the higher-than-average prediction.

So why haven’t we seen anything along the lines of Hurricane Ida? Other conditions are inhibiting storm formation, said Daniel Gilford, a climate scientist at Climate Central.

“There is air blowing over the Sahara Desert that is fairly dry,” Gilford said. “That dry air tends to suppress the growth of storms.”

Gilford says warm oceans fuel hurricanes. That’s why climate change, which is warming the oceans, has increased the likelihood of more intense storm systems. While all of that excess heat drives the creation of high winds characteristic of tropical storms, hurricane creation itself requires low winds.

“We’re not actually seeing the winds calm down in the Atlantic Ocean,” said Gilford. “We’re seeing really strong winds, especially at higher altitudes. And what that does is it creates something called the wind shear.”

He says the wind shear acts to suppress storm formation by toppling any developing hurricane systems. Think of it as if you were blowing on a spinning top. “That’s exactly what’s happening with the wind shear. It’s literally tilting over the storm.”

Gilford said that despite these opposing atmospheric forces canceling each other out, chances are pretty good a major storm will develop within the next three months.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.