Hundreds pack Fitler Square school auditorium to disagree over proposed protected bike lane pilot

City residents gathered Monday evening in Fitler Square to fight over what may be the neighborhood’s most precious commodity: space.

Curb-to-curb, Lombard and South Street both sit just 26-feet wide.* On those narrow strips of asphalt a competition for space rages between pedestrians, bikes, parked cars, moving cars, delivery trucks, taxis, Ubers, and buses. It never really all fits, leading to clashes both violently literal and noisily metaphysical.

Formally, the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems (OTIS) held the meeting to introduce, and solicit public feedback on, a proposal to pilot protected bike lanes on South and Lombard Streets for six months. The lanes would adorn largely faded, non-protected bike lanes on Lombard and South Streets with plastic delineator posts.

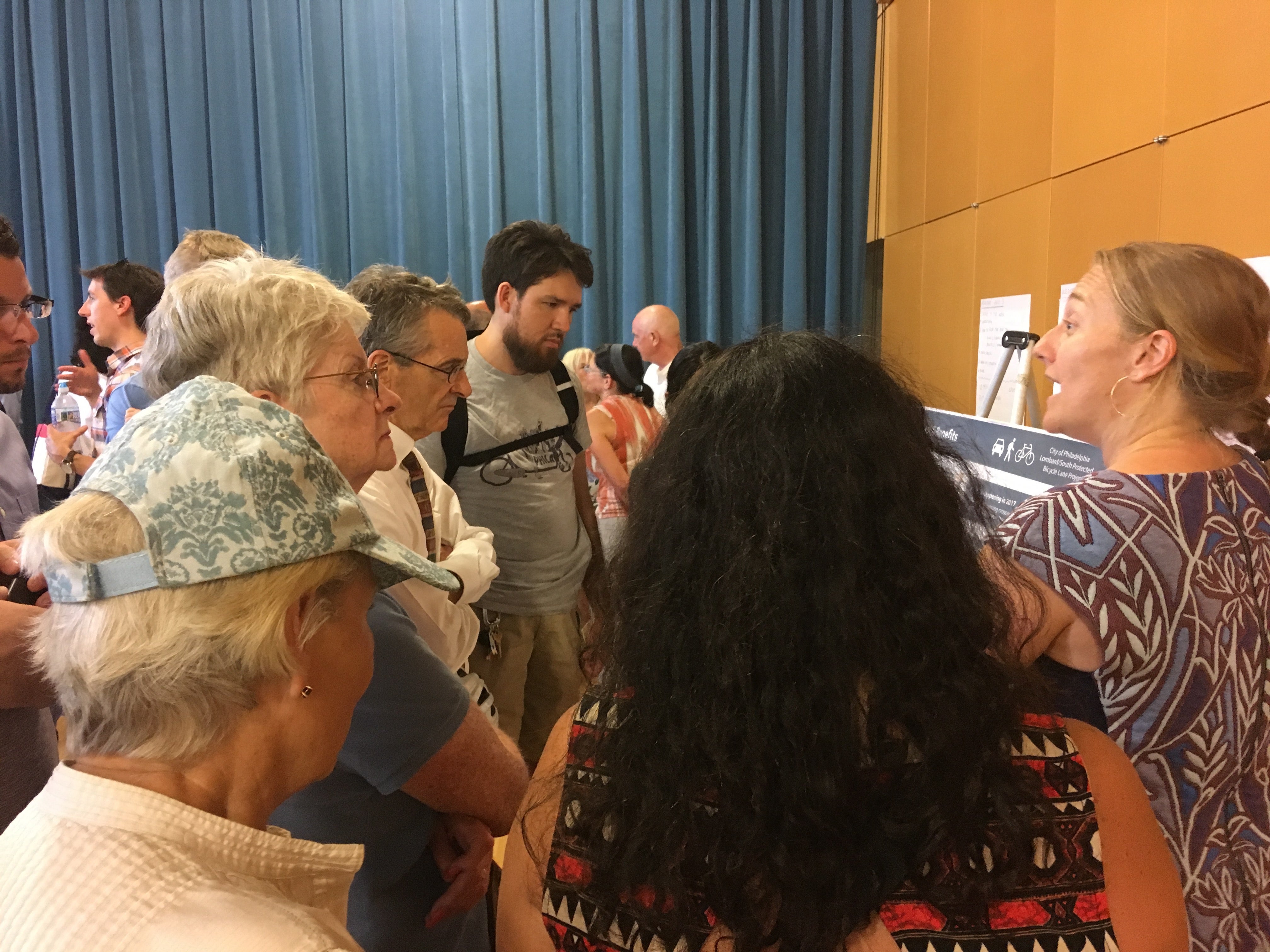

Informally, Monday’s meeting served as an opportunity for community members to meet their neighbors, who, many seemed to decide in advance, are outrageously and obviously wrong. Few in the crowd of over two hundred seemed to have come to the private school auditorium without strongly held, preconceived notions over who ultimately owns the public right-of-way.

Automobile-favoring residents denounced the idea of not being able to idle their cars directly in front their homes, citing children to carry, groceries to unload, and infirm elders to walk inside. Advocates for the protected bike lanes questioned why their lives should matter less than someone else’s convenience.

There were calmer heads in the crowd, a few willing to concede that the other side had some valid points—parking in Fitler Square can be a nightmare; biking in traffic can be a nightmare—but they were outnumbered by those afraid of the proposed changes, or afraid the proposed changes would never come. On its blog, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia asked supporters to avoid treating the information session as a debate and to keep things civil, a plea met with mixed deference.

In the face of heated rhetoric, OTIS staff kept cool, mostly listening as the proposals defenders and attackers fought it out rhetorically in front of them, chiming in only to correct frequent factual inaccuracies made by members of the crowd. They, and some of the more experienced members of the Bicycle Coalition, have become old hands at calmly listening as antagonistic neighbors talk past one another.

Representatives from 2nd District Councilman Kenyatta Johnson’s office were on hand to take the temperature of the crowd and “gauge where a strong majority is,” on the issue, said Johnson’s legislative director, Joshu Harris.

When asked whether the protected lane proponents needed a strong majority to overcome inertia, Harris quickly added that an absence of consensus on protected lanes didn’t necessarily mean nothing would change. “I’m not going to say the status quo is where we’re at if we don’t have that [strong majority],” said Harris, noting it was often difficult to figure out the community’s will.

From the crowd gathered alone, no clear majority seemed to emerge. “I think it’s a lively debate on both sides as far as concerns on what it would mean to have delineators put out,” said the office’s director of complete streets, Kelly Yemen. Harris said Johnson’s office would continue to solicit more community input on the matter.

The proposal would also redirect school bus parking for the Philadelphia School from Lombard Street to 25th Street. Currently, the buses are allowed to occupy the bike lane on Lombard to pick up and drop off students.

The proposed pilot of protected lanes would run over the warmer months next year. After measuring traffic impacts for six months, OTIS would then report back to the community, said Yemen.

Even though the city has piloted bike lanes in the past only to subsequently remove them, local opponents said they feared OTIS staffers were merely paying lip service to the idea of listening to their concerns. Noticing the chummy familiarity among OTIS staff and some of the bike-infrastructure advocates, who have become familiar faces at these neighborhood meetings, they feared the flimsy posts were fait-accompli.

“Once you go down a pilot phase, it’s much more difficult to remove it, and I’m not sure there’s going to be that opportunity again,” said Aaron Goldmuntz.

Goldmuntz said he appreciated the meeting, but the lack of an organized record of the community’s comments—OTIS staff collected feedback in the form of post-it-notes stuck to presentation—gave him pause. Goldmuntz, who held his three-year old son in his arms as he spoke to PlanPhilly, said he wasn’t opposed to bike lanes, or even the idea of some sort of physical separation between bikes and cars. A cyclist himself, Goldmuntz said he takes his son to preschool by bike.

But, Goldmuntz added, erecting fixed barriers that would prevent him from unloading his car in the bike lane would make the already difficult task of raising a toddler and infant twins harder still.

Even if community opposition may derail the delineator posts, bike infrastructure advocates could have reason to cheer. While the no-crowd was steadfast in their opposition to protected bike lanes, many echoed Goldmuntz’s position: They had no problem with bike lanes painted in bright lime green.

It wasn’t too long ago that the idea of putting bright paint down to mark a bike lane was a bridge too far in Philadelphia: Initial proposals to paint the South Street Bridge’s bike lanes green were shot down. That the subset of local residents who dislike the idea of protected bike lanes are at least open to a paint-protected alternative suggests that attitudes over the right of bicycles to occupy the street has shifted.

Still, while the delineator post opponents held out non-protected bike lanes as a compromise, the pro-post crowd did not find street greening a satisfactory alternative. They stated that paint, regardless of how verdant its hue, cannot physically keep cars from occupying the bike lane. While some studies suggest that drivers avoid painted lanes more than basic, non-painted, bike lanes, those protected with delineator posts, raised planters, or car parking, clearly separate traffic more effectively.

There’s a potentially bigger problem with painted lanes than their perceived ineffectiveness among a subset of cyclists. Philadelphia remains a cash-strapped city that scrapes together revenue for bicycle infrastructure from obscure funding streams and grant programs. The long-lasting lime paint isn’t cheap, costing upwards of $9 a square foot.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.