How we ended up with lead piping and why removing it will be hard

Listen

Tom Bigley

Historically, engineers and government officials pushed for the use of lead in water infrastructure. Now, removing it will take a lot of money and effort.

In Vogt True Value Hardware on the Southside of Pittsburgh the stock of plumbing pipes includes copper and plastic. The owner of the neighborhood store, Shawn Vogt, shook his head no when I asked if he carries any lead lines.

“It’s no longer legal,” he said. “That’s like an old fashioned thing.”

The store hasn’t carried any lead pipes in decades, he said.

“The [Environmental Protection Agency] monitors the city and they actually did a run through here probably within the past year checking all the hardware stores to make sure that there isn’t anything on the shelves. And we didn’t have any,” he said.

With a chuckle, he added, “I think it’s pretty common sense that you don’t want lead in your drinking water.”

That wasn’t always so.

A good investment

“From a purely engineering perspective, lead had attractive features. It was durable, and it was malleable,” said Werner Troesken, professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh and author of “The Great Lead Water Pipe Disaster.”

Lead pipes came in big rolls, which plumbers would unroll into ditches leading from the water mains in the street to individual homes and buildings. Over time, as the ground settled and shifted the soft lead pipes would move with it without cracking or breaking.

These connecting pipes, called service lines, were often owned by the homeowner — not the utility — but the city engineer or other officials dictated the materials the homeowners could install. (For the bigger mains in the streets lead was too expensive and too soft.)

“If you go back and you read the engineering journals from, say, 1900, you find lots of quotations from engineers saying, ‘Lead’s going to last a really long time. This is really the Cadillac of pipes, we want to use it,’” Troesken said.

In many cases, pipes installed 100 years ago are functioning fine.

At the same time, the health effects of lead at that time were minimized. In the 1800s and early 1900s, some doctors linked miscarriages and various health issues to lead poisoning from pipes, but their data was bad, often relying on case studies rather than quantitative evidence. Other pollutants were a bigger concern. Lead poisoning was a slower, more elusive problem. Cities were dealing with rising death rates caused by bacteria.

“Compare that to if someone says cholera is a problem or typhoid is a problem. Cholera can kill you in 48 hours,” Troesken said.

In Pennsylvania, at the turn of the 20th Century, most cities were installing lead service lines.

Prolonging lead’s reign

When officials did start to accept that lead wasn’t all good, the industry fought back.

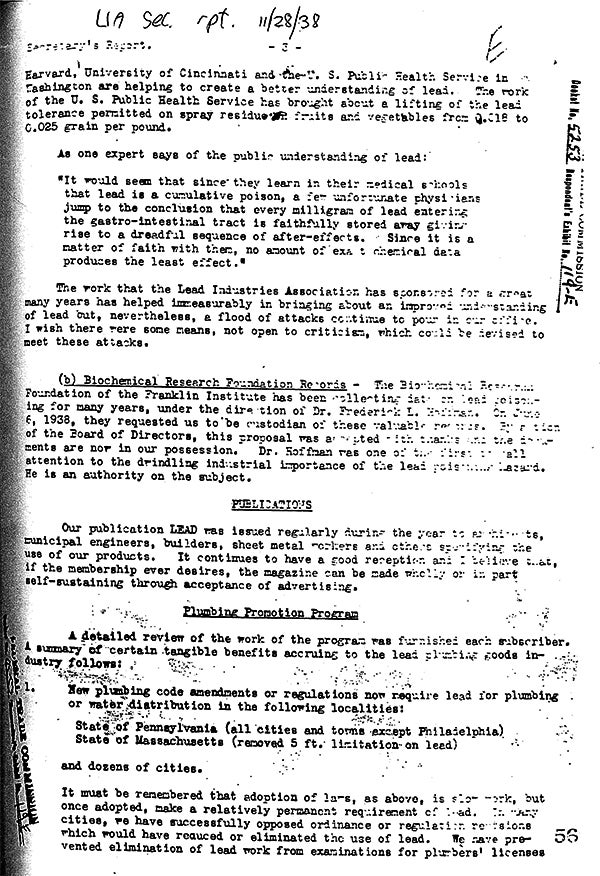

A page from the Lead Industries Association’s 1938 report, which says Pennsylvania was one of the places where they successfully lobbied for new regulations requiring the use of lead in plumbing.

Richard Rabin, a public health professional who’s written about lead, said the industry prolonged its product’s reign by lobbying. The Lead Industries Association (LIA), formed in 1928 by companies with a stake in lead sales, sent representatives to meet plumbing associations, plumbing code writers, and local, state and federal government officials.

In a 1933 report, LIA reported: “We have rekindled an interest on the part of master and journeyman plumbers in the use of lead. We have pointed out to municipalities the risks that they run in advocating substitutes for lead and have received the endorsement of [those] with whom the subject has been discussed.”

They urged localities “to keep using lead pipes. And in fact even where lead pipes were banned they were able to get those bans overturned,” Rabin said.

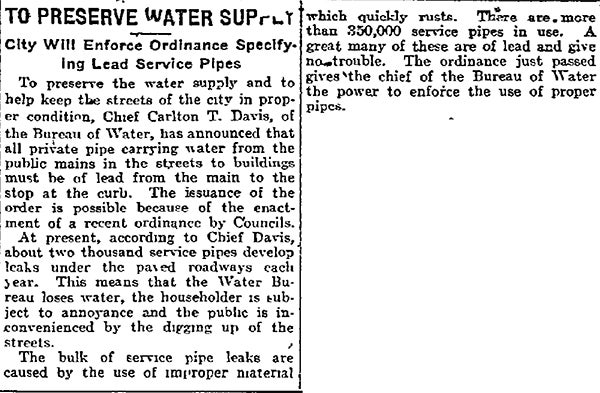

A 1916 article from the Philadelphia Inquirer announcing ordinances requiring the use of lead for pipes.

Philadelphia already required lead lines in the early 1900s. According to LIA’s meeting minutes from 1938, the organization successfully pushed codes requiring lead for plumbing in the rest of Pennsylvania that year. In addition, LIA reported that they helped “establish classes teaching lead work to plumbing apprentices and journeymen in order to insure an adequate future supply of mechanics who can install lead” in places like Pittsburgh and Wilkes-Barre.

LIA acknowledged the increasingly accepted understanding of lead as dangerous to the body without agreeing with the scientists who promoted that view. “I wish there were some means, not open to criticism, which could be devised to meet these attacks,” LIA’s Secretary wrote in 1938.

Lead’s legacy

At a training center for plumbers outside Pittsburgh, Tom Bigley, Director of Plumbing for the United Association of Plumbers and Pipefitters, walked past a wall lined with toilets and clear pipes, past a two-by-four skeleton of a house where students practice various plumbing skills, and stopped in front of a simulated water main with several service line connections. He picked up a sawed off chunk of lead line with a bulge where it connects to a valve. The bulge, called a lead wipe, is a type of joint, one that required considerable skill to make.

A piece of lead service line instructors at the Pittsburgh Plumbers Local No. 27 training school use to teach students about working with older plumbing.

“They don’t do that anymore, but that was part of the trade,” Bigley said. “That’s where [plumbers] got their name from. That’s a Latin word for lead wiper.”

Bigley started plumbing in 1980, but he never learned how to make those joints. By then lead was a little passé. Copper became the material of choice, then plastic. Plus, officials had finally accepted as fact the negative health effects of lead exposure. Little by little, some municipalities had moved to ban the use of lead in plumbing and the federal Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1986 limited lead’s use nationwide.

But many old lead lines remain.

While corrosion control programs help keep water safe, the only guaranteed way to control lead exposure in drinking water is to remove all lead from the system.

The call to replace all lead lines is complicated and expensive.

For one, in many cities homeowners still maintain ownership of the service line, in part or, sometimes, in its entirety. Mandating their replacement means imposing significant costs on homeowners — replacing it can cost thousands of dollars — or finding ways to reimburse them for the expense. While some municipalities, like Madison, Wis., provide reimbursements for lead removal, Keystone Crossroads found no such programs in Pennsylvania.

Two, it’s not always clear what it means to remove lead. Old homes can have lead service lines, indoor plumbing with lead content, lead solder, leaded copper pipes, and even lead fixtures. The 1986 rule banning lead defined “lead free” as 0.2 percent lead in solder and 8 percent lead in pipes. That definition was amended in the 2011 Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act, which brought down the level of allowable lead content in pipes to .25 percent. That definition has only been in effect since 2014.

John Inks, Training Director at the Pittsburgh Plumbers Local No.27, where the training school is located, seemed overwhelmed by the thought of wholesale removal. “Where’s it going to stop? I don’t know, you’re talking a lot of infrastructure,” Inks said.

Perhaps the hardest part of all is lead’s slippery pervasiveness: it’s everywhere, but no one knows where exactly. It’s not mapped, not documented. The Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority has no idea which houses have lead service lines, but recognizes the old age of homes in the city means many of them do. The Philadelphia Water Department estimates 60,000 properties have lead lines, but doesn’t know which ones.

Flint, Michigan’s lead disaster has brought all this into stark light. Pittsburgh’s water authority, for one, is planning to try and identify where the lead lines are. And both the Pittsburgh and Philadelphia utilities are starting to think about what it would take to replace them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.