How vaccine sites can be more accessible to people with intellectual disabilities

Jefferson’s Center for Autism & Neurodiversity has been working with focus groups of young adults to craft strategies.

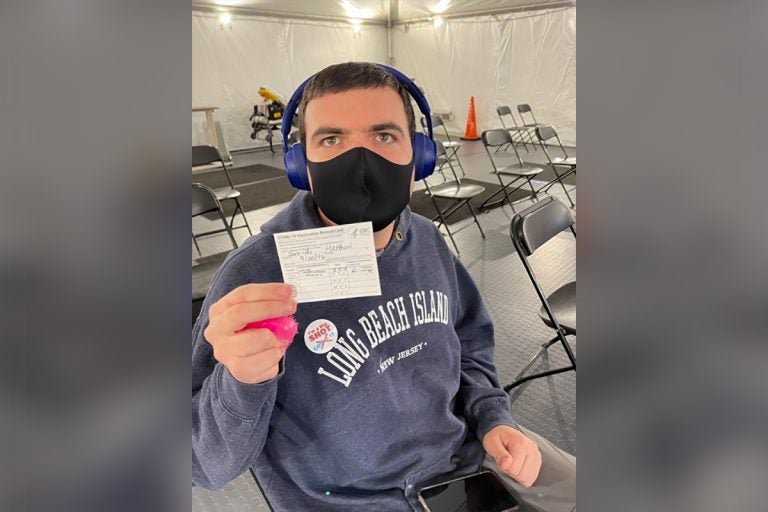

Matthew Smith getting his vaccine. (Courtesy of Eileen Smith)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

Many of us are still looking forward to that “I got vaccinated” sticker.

But tangible signs they did a good job getting the COVID-19 vaccine might be even more meaningful for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities who think or process differently, and for whom things like routine medical care can pose challenges.

People with intellectual disabilities are now eligible for the vaccine in Delaware and in Philadelphia, where city Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley announced in mid-March that they were included in Phase 1B of the vaccination effort. New Jersey announced Friday that vaccine eligibility in that state would begin April 5.

Now that the vaccine is more available, Wendy Ross, director of the Center for Autism & Neurodiversity at Thomas Jefferson University, has been working with focus groups of young adults with intellectual disabilities to craft strategies toward making it more accessible. Some of those groups have been based out of Carousel Connections, a Philadelphia-area training program for people with disabilities that tries to build independence.

“I think one of the pieces in this experience is for participants to be able to share out,” said Amy McCann, CEO and program director at Carousel Connections.

She described how during one group, the participants went back and forth on noise-canceling earphones — some people like them, some people find them uncomfortable.

“A strategy isn’t a one size fits all, but everybody has a voice,” McCann said.

Managing expectations around the vaccine has been difficult because of the “up in the air” nature of the vaccine rollout, McCann said: Knowing it’s coming, but not knowing who would get it or when. Because some of the individuals at Carousel Connections became eligible because of other health conditions, that variability and difficulties finding appointments even for those in priority vaccination phases took a toll.

All that is compounded by the danger. People with intellectual disabilities are being included in most priority vaccination phases now because they have faced higher risk during the pandemic.

“We were starting to have families learn of loss,” said McCann, “either family members or peers that have passed away, and the yearning to have the vaccine became even more dire.”

Research done at Thomas Jefferson University was cited by Philadelphia Health Commissioner Farley in the decision to include people with intellectual disabilities in the city’s Phase 1B. The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst, found that individuals with intellectual disabilities not only had a higher risk of coronavirus infection and being admitted to the hospital and ICU, but were also more likely to die.

Fostering a sense of security

For McCann, there have been three issues surrounding vaccination: having basic access, getting priority access to match with the need, and “having access to situations that feel comfortable.”

Getting the shot hurt a little bit, but now “I feel safe,” said Tierra Daniels, a Carousel Connections participant, in recounting her feelings after being vaccinated.

Natasha Black, also a participant in Carousel Connections, took the vaccine in stride. “It was exciting because when you take the COVID-19 vaccine, you’re going to have colds, headaches, or stuff like that, [but] it prevents [you] from getting coronavirus,” she said. After her first dose, she had a minor headache, Black said, but she added she is excited at the prospect of making more friends in person after COVID.

Sarah Immerman, a Carousel Connections participant who lives in Lower Gwynedd, went all the way to Harrisburg to get a vaccination. She said she felt tired after getting the shot, but added that now she knows she’s healthy.

McCann and the Carousel Connections team are keeping families up to date with any and all vaccine opportunities, but she noted that many of the families have been lucky enough to have access to them. She doesn’t think this is the case for everyone, adding, “I don’t think that is the case in the world of folks with an intellectual disability.”

Ross, director of Jefferson’s Center for Autism & Neurodiversity, said, “We’re all somewhere on a spectrum … if you have an intellectual disability, you have autism, we are all on the human spectrum.” She believes that greater vaccine accessibility will actually benefit everyone.

What does a more accessible vaccination site look like?

With Ross, the young adults at Carousel Connection put together a list of things people with intellectual disabilities might want their vaccinators to know:

- I might feel anxious, and a new environment with loud noises and bright lights might make this worse. If the room cannot be less overwhelming, consider offering me noise-reduction headphones and/or sunglasses to reduce my sensory overload.

- I sense negativity, so please try to be positive. I cannot see you smile behind your mask, so please use a friendly tone of voice. Be patient with me — sometimes, it takes me a minute to follow directions and answer questions.

- Distraction helps me. Tools like fidgets or holding someone’s hand, like my caregiver’s, can help. I may not think to start a discussion to distract myself, so please feel free to begin a discussion with me. Some things that you can ask me are my favorite song or activity. Or even ask me what helps me feel calm.

- Encouragement helps. Please tell me that I am doing a good job, or that I am being brave and strong.

- Be clear about expectations. If I am waiting and being watched for 15 minutes, please give me updates on the time. Having a checklist along my vaccination journey can also help.

- A reward or a sticker at the end always helps.

Ross envisions these guidelines being used by everyone.

“These are things that vaccinators can know, whether they are in your local pharmacy, or they are part of a vaccination center,” she said.

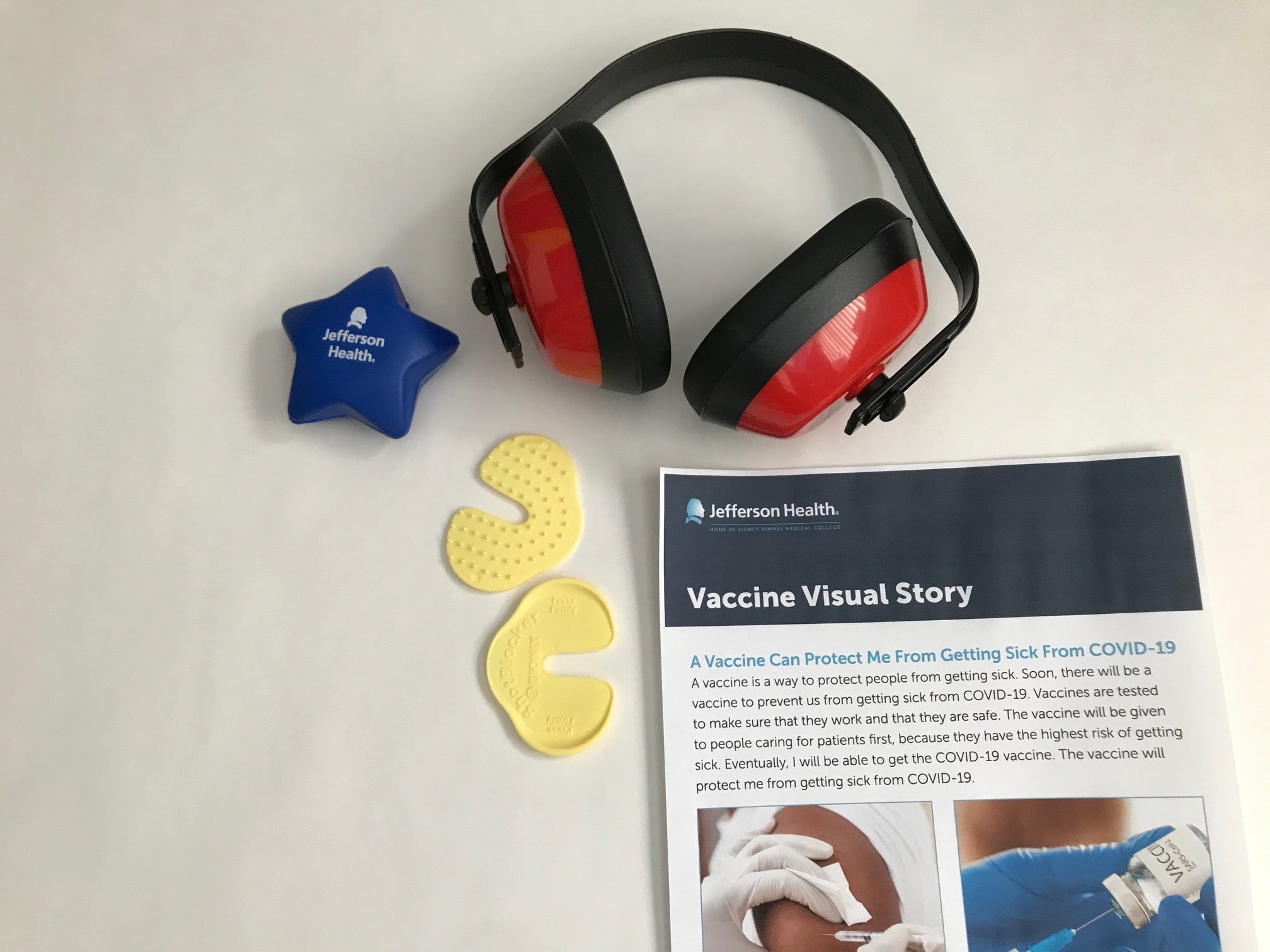

In addition, Ross has put together a toolkit that includes visual stories, shot blockers to reduce pain, fidgets, noise-reduction headphones, and sunglasses.

The visual story, available online, can be used by people who are getting the vaccine and could benefit from seeing all the steps laid out. The shot blockers reduce the feeling of getting an injection, “they’re prickly on one side, so they help disperse the sense of the needle,” Ross said.

None of these things are specialized, she said, “we have things that even local pharmacies can buy,” she said. Anything handed out would, of course, need to be single-use, to prevent possible spread of the virus, but Ross also hopes families may have some of these things already.

Some of the guidelines are universal — most people like to be told they’ve done a good job.

“I think that there is a lot of conscious and unconscious bias about those with intellectual and developmental disorders,” said Ross, “and I think the only way to overcome that bias is … for everybody to kind of jump in and just get to know each other.” She hopes the vaccination effort might even be a way to bring people from different communities together.

The guidelines and the toolkit can be implemented on an individual scale, but there are bigger steps that can be taken, Ross said. She suggests offering these individuals the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, which, unlike the others, is a single shot. Also, the physical design of the vaccine location — some sites have chairs that rock, or sensory spaces people can use for their 15-minute wait. These can all be great resources, assuming they can be sanitized and kept COVID-safe.

There are hundreds of vaccination sites run by different agencies, groups, and organizations. But Jefferson is working to implement some of Ross’ strategies at its sites. And Philadelphia Department of Public Health spokesperson James Garrow said caregivers are allowed at city sites and the FEMA-run Convention Center site has a special program for people who might want assistance.

Ross hopes her ideas will be used broadly. She is still working to implement some of them in Philadelphia, but she thinks that any vaccination site can adopt them.

“I don’t want to hoard the information. I want people to get vaccinated. That’s the goal,” she said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)