How community organizers fought deportation in Philadelphia and won

After years organizing by a coalition of immigrant rights groups, Philadelphia passed a landmark policy stopping the imprisonment of people on behalf of federal immigration authorities. It is one of the most progressive immigration policies in the country, and it highlights changing perceptions of crime and the roots of violence.

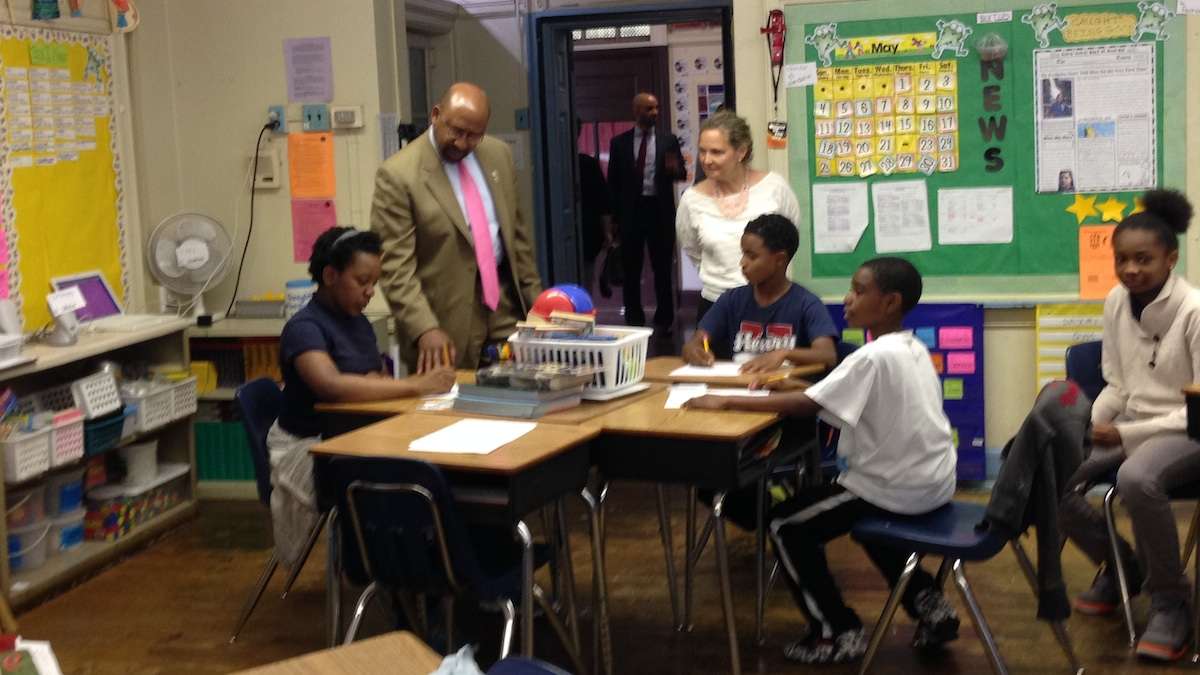

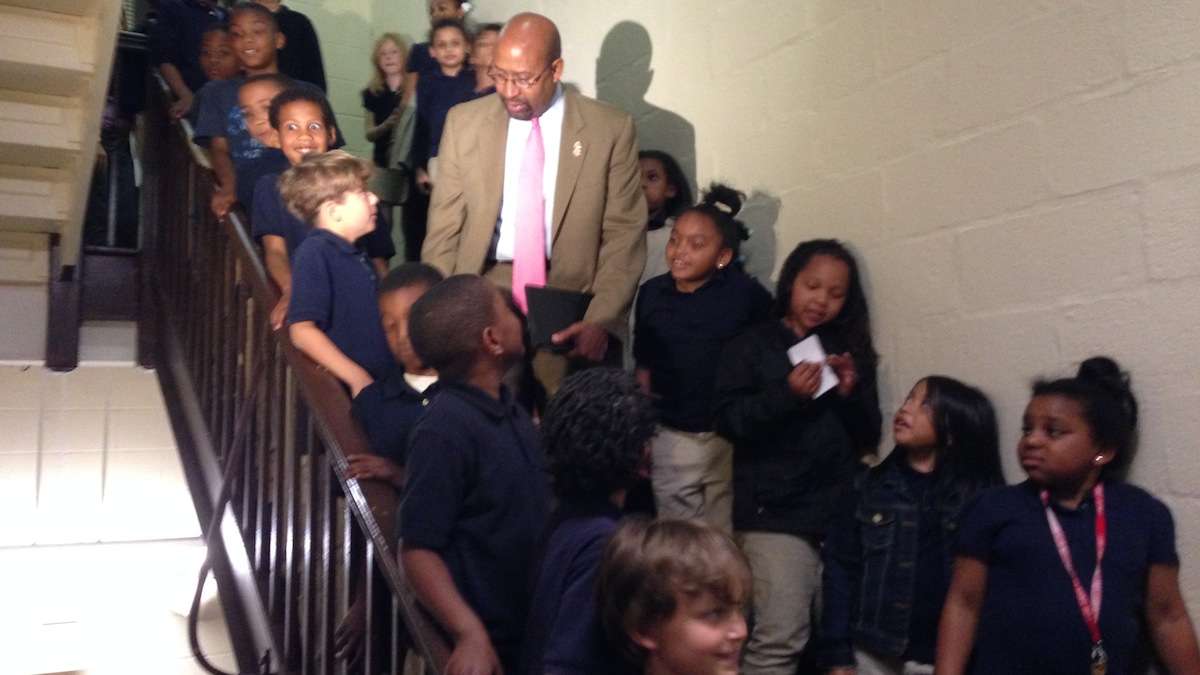

After months of back-and-forth with Philadelphia’s immigrant community, Mayor Michael Nutter signed a landmark executive order on April 16 ending the practice of “ICE holds,” the requests Immigration and Customs Enforcement sends to police to detain immigrants so they can be taken into federal custody for deportation proceedings.

The new policy comes after years of community organizing by the Philadelphia Family Unity Network (PFUN), a coalition of immigrant rights groups spearheaded by New Sanctuary Movement, Juntos, 1Love Movement, the Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizenship Coalition, and Victim/Witness Services of South Philadelphia.

While the messaging from organizers and the administration has seemed contradictory, PFUN’s community organizing not only generated one of the most progressive immigration policies in the country; it also highlights rapidly changing perceptions of crime and the roots of violence.

As the group began to form, the issue of advocating on behalf of immigrants with certain criminal backgrounds became a central point of contestation, both between organizers and the administration, and within the coalition itself. As organizers developed a campaign strategy, they decided to unite in resisting any policy that engaged in what Mia-Lia Kiernan of 1Love Movement called “harmful divisions over criminal history or levels of criminality.”

In the months leading up to the executive order, organizers began discussions with city officials, the media, and community members about the importance of a policy that did not distinguish between immigrants based on criminal history.

“Our faith values not only influence how we think about those who are undocumented but also those who society kicks out,” said Nicole Kligerman of New Sanctuary Movement. “We can’t deport violence and expect to have a healthier world. The way to create safer communities is by finding healthy solutions to social problems, not by expelling and disposing people or locking them in a cage.”

The administration claims that the policy reflects Mayor Nutter’s commitment to “keeping violent people off the street,” by allowing ICE to detain persons convicted of certain felony offenses. Under the new policy, however, ICE can only detain these persons when they secure their detainer with a federal judicial warrant. As there is no clear method for ICE to obtain a federal judicial warrant, organizers claim that the executive order will effectively put an end to ICE holds in Philadelphia and impede deportation.

At almost two million, Barack Obama’s presidency has seen the highest number of deportations in U.S. history. The New York Times published a graphic in 2013 showing that this figure is nearly the same as the number of deportations between 1892 and 1997.

The first battle

While organizers have been challenging various iterations of police/ICE collaboration in Greater Philadelphia since 2006, PFUN’s specific campaign to end ICE holds began last June. Caitlin Barry, an immigration lawyer and law professor, and Jasmine Rivera, an organizer with Juntos, drafted language for an executive order in Philadelphia demanding a stop to all ICE holds regardless of criminal history.

They presented their draft order to Fernando Trevino, deputy director of the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant and Multicultural Affairs (MOIMA), who told them that the administration would agree to a policy ending ICE holds except for people charged with Level 1 offenses, a broad category which includes homicide, sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, resisting arrest, and drug offenses involving a prison term of over a year. This proposed policy would allow ICE to continue to detain and deport immigrants charged with such offenses. Trevino told community organizers that Mayor Nutter wanted to pass this executive order by the end of August.

While only 12 percent of detained immigrants have been convicted of a Level 1 offense, PFUN continued to reject any policy that allowed ICE the ability to detain and deport immigrants with certain criminal histories.

“The city’s first draft of this executive order would have excluded a section of the community and was contrary to our principles against systems that criminalize communities of color,” said Rivera.

Trevino, however, maintains that organizers deserve a lot of credit for the final policy and received full support from City Council and the Mayor.

“As a former community organizer and advocate,” said Trevino, who said that the initial policy was only a conservative draft, “I understand that you always ask for everything you can get and then later compromise. We’d tell the advocates that they needed to keep pushing and keep doing their job. But we were going to keep doing our job to have a policy that benefits every single individual in Philadelphia.

“It’s not a good policy to have people convicted of violent crimes to be on our streets.”

1Love Movement’s Kiernan said that the administration’s reluctance to support the organizers’ demands reflected larger divisions within the immigrant rights community.

“It’s hard for people to connect the movement to health care, labor, education,” Kiernan said. “When we’re talking about immigrant rights in relation to mass incarceration, it takes a lot of education to make that link.”

Building a united coalition

Over the next few months, organizers turned inward to discuss campaign strategy. Disagreement quickly surfaced within the group over the pragmatism of advocating for immigrants with criminal backgrounds.

1Love Movement, a Cambodian-American organization, pushed the coalition to unite over a policy that would end all ICE holds and took steps to educate the coalition about their community’s experiences and the relationship between structural violence and the proposed language of the city’s new policy.

1Love Movement came together in 2010 after four Cambodian-American refugees were detained by ICE for crimes they had committed in their youth. One of the four men, Chally Dang, was arrested after firing an illegal handgun into the air when he was 15. Dang was charged with aggravated assault, criminal conspiracy, and possession of criminal instruments, and he was sentenced to five and a half years in prison. He was taken into ICE custody after being paroled at the age of 21 and given a final deportation order to Cambodia, a country he had left as a child.

“Because of the violence [in the community],” said Naroen Chhin of 1Love Movement during his testimony to City Council, “many of my friends ended up being charged with adult crimes even though they were teenagers. Because they were not citizens, they were given a double punishment when they left prison and then had to face deportation.”

“Spiritually and politically, New Sanctuary Movement is driven by creating just and welcoming communities regardless of immigration or criminal status,” said Nicole Kligerman, a community organizer with New Sanctuary Movement. “But I give a lot of credit to 1Love in terms of showing us that it was possible to hold that as not just a spiritual value, but as a real campaign value that we could win.”

After a series of town halls, organizers had united their communities on key principles and defined a victory as the ending of all ICE holds regardless of criminal history. PFUN began discussions with key members of City Council who were publicly supportive of such a policy.

Refusing to compromise

A few days before the public hearing, MOIMA and the director of public safety, Mike Resnick, invited PFUN to City Hall. For the first time since August, the administration presented organizers the language of Mayor Nutter’s proposed executive order. The administration was now proposing a policy that allowed ICE to detain and deport an immigrant convicted of a Level 1 or Level 2 felony (offenses resulting in over seven years of incarceration), if ICE secured a federal judicial warrant.

Having spent the weeks leading up to the hearing organizing community members to testify, PFUN told the administration that they would proceed with the hearings.

“Our members deserved their time to testify,” said Kligerman. “Not just as victims of deportation, but as community leaders who’ve worked since 2007 for this and have had their family members deported due to unjust ICE holds. This was their opportunity to share their strength and leadership in a public forum that has systematically left them behind. The power that people felt upon testifying was overwhelming. The leadership that was built through the campaign was tremendous.”

Organizers also felt that the administration’s resistance to a policy that ignored criminal history didn’t reflect local and national efforts to divert people from prison and provide second chances for people returning from prison.

“We’re taking a lot from Attorney General [Eric] Holder and his initiatives to address the mass incarceration crisisand how it disproportionately affects poor people of color,” said Kiernan. “One in five people in Philadelphia are formerly incarcerated. Those values of rehabilitation, redemption, and transformation we have started to give them should be applied to the immigrant community.”

A final change in policy

Organizers obtained Resnick’s proposed executive order a few days before the public hearing.

“We as a coalition had to research how this policy would impact our community,” said Andrade. “We wanted to make sure the addition of the judicial warrant would end the use of ICE Holds in Philadelphia, and it does.”

According to Jonah Eaton, an immigration lawyer in Philadelphia, the existing legal infrastructure does not currently exist for ICE to easily get such warrants.

“ICE and the federal judiciary may figure this out,” said Eaton, “but for the time being, the administration has effectively shut down ICE holds regardless of what they say about first or second degree felonies.”

The administration maintains that their policy continues Mayor Nutter’s efforts to keep “violent people off the streets.”

“The policy is not [a contradiction] because we are following the law,” said Trevino. “There’s a recent opinion by the Third Circuit requiring a judicial warrant. If the mechanism doesn’t exist, to be honest, it’s up to ICE to figure it out, not us.”

1Love Movement issued a statement saying that they will continue to push for a “culture shift” regarding how policymakers and the public address the roots of violence.

“We remain cautious in the policy’s framing that continues to draw lines of who is deserving and who is not based on criminal background,” read the statement. “While we have moved mountains in policy and legal language that will now protect more people than ever before, we continue to be faced with a destructive societal and political culture of judgment, exclusiveness, and scapegoating. It urges us, as a movement for dignity, justice and fairness, to focus on the pieces of movement work that promote shifts in our culture as a society — the community organizing.”

The signing ceremony

A day before the signing ceremony, MOIMA told organizers that there would not be enough time for members of PFUN to speak. Organizers held their own press conference in the hallway to not only translate the complexity of the executive order for the media, but also claim the final policy’s relationship to the criminal issue as a victory.

“History has a tendency to forget the role of communities in creating change and usually offers a version that only applauds elected officials and those in power,” said Andrade. “We must never forget the amount of work and dedication community members and leaders have given to make policies like this possible.”

Jim Engler, legislative director for Councilman Kenney, believes that community organizers were chiefly responsible for the executive order.

“This was PFUN’s victory,” said Engler. “They organized and organized and organized to the point that the administration’s resistance to what they wanted was going to be impossible. If they didn’t keep pushing, I don’t think the administration would have gotten there.”

Organizers have hailed the executive order as a victory for immigrants in Philadelphia, calling it one of the most progressive policies in the country.

“There were disagreements during the campaign with some government entities but we ultimately ended up with a terrific ICE hold policy,” said Blanca Pacheco, a community organizer at New Sanctuary Movement. “As with any big progress, there is tension about both the substance of the policy and the method of working. Through that tension, we’ve raised the standard of what meaningful community engagement looks like in Philly.”

Proper implementation and looking forward

All eyes are now set on implementation of the executive order. “If someone violates the new policy,” said Andrade, “police captains ought to understand that violators shouldn’t just get a slap on the wrist because it makes the work of police that much more difficult.”

There is already fear among organizers that ICE might consider conducting more raids in Philadelphia or collaborating much more aggressively with police in smaller Pennsylvania cities like Allentown and Reading. The former has happened in cities like New Orleans, where, after the sheriff’s office announced it would decline most ICE holds, federal officers began conducting home and neighborhood raids.

“We have already brought up the issue of implementation with the city,” said Rivera. “We as a coalition are prepared to do the work necessary to properly implement and oversee this policy.”

The White House recently announced a review of the administration’s deportation programs in an effort to make them “more humane.” While immigrant rights groups are divided over national strategy, PFUN’s organizing efforts in Philadelphia demonstrate that, even as Washington may continue to stall, local venues can play a vital role in stopping record numbers of deportations.

PFUN has already been contacted by community organizers in other cities working against ICE holds and deportation.

“In order to create effective change on a national level, you need to have local victories,” said Rivera. “You have to show the direction the country is moving in. Whenever we do local campaigns, it’s always connected to larger issues. Our fight is connected to the national fight.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.