New Jersey’s statewide housing woes are reflected, magnified in Trenton

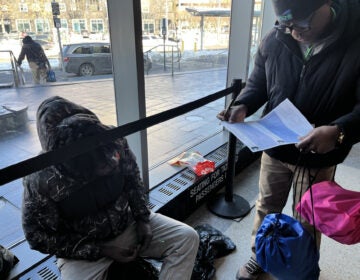

Trenton, N.J. (Alan Tu/WHYY)

If New Jersey’s political leaders want to study the state’s battered housing market, all they have to do is look out their windows in Trenton.

As most of the nation continues to recover from the Great Recession, real-estate data and analysis firms report housing sales are slowing and foreclosures increasing in the Garden State. But the situation is particularly dire in the state’s capital city.

Around the nation, foreclosures have declined to their lowest level since before the housing bubble burst in 2007, according to RealtyTrac of Irvine, CA, whose data is used by the real-estate industry and government agencies.

But in New Jersey, state court records show 31,500 new foreclosures cases have been filed as of Aug. 1, on track to be at least the third-highest annual total in state history. Sheriff’s sales have hit a four-year peak, and bank repossessions almost doubled in May.

Some towns are doing better, but only with modest recent gains, New Jersey sale prices are still down 22.2 percent from the pre-recession peak, according to CoreLogic, another Irvine, CA, analytics firm. That is worse than all but four other states, the firm found.

Trenton could be the poster child for New Jersey’s mix of economic weakness, a troubled housing market and ineffectual political responses.

The 2,473 foreclosure homes in Trenton represent 21.5 percent of the city’s homeowner properties as reported by the U.S. Census as of 2012.

Even a relatively obscure statistic reflects significant trouble. RealtyTrac’s latest numbers show more than twice as many homes in the state capital area are in foreclosure, or have already been seized by banks, than the total number the firm currently lists for sale.

Trenton is dealing with a number of issues:

Former Trenton Mayor Tony Mack was elected in 2010, as towns around the state were fighting to regain their financial footing. Three months ago, Mack was sentenced to almost five years in prison for accepting tens of thousands of dollars in bribes. That hasn’t helped the city’s image.

Like Atlantic City, drained financially as casinos close, Trenton’s economic vitality has relied on a dwindling industry — state government.

As recession-induced budget cuts hit police forces, other New Jersey municipalities have seen crime rise. But in Trenton, safety concerns have undermined the city’s image as well as its stability, according to James Hughes, dean of the Edward J. Bloustein School of Policy and Public Planning at Rutgers.

“Think of New York City and its comeback,” Hughes said. “A lot of it has to do with reduction in crime and perception of safety — Trenton is the exact opposite.

“All the Italian restaurants are gone — people told them they didn’t feel safe coming at night — and much of that community has moved to Ewing or Lawrence,” Hughes said.

Even on RealtyTrac, some raw numbers appear even more calamitous in a few other communities, such as Paterson or Newark. But housing sales are up in both those cities on a year-over-year basis, which is preferred by analysts because it avoids seasonal fluctuations. In both cities, median prices are about $150,000-$160,000 and even bank-owned homes average $107,000-$110,000, a smaller gap than the New Jersey average.

In Trenton, the data show sales are down 26 percent from a year ago. So far this year, 19 percent of homes sold in the city have been at sheriff’s sale, by banks after foreclosing, or short sales, in which borrowers are able to walk away from “underwater” mortgages that saddled them with more debt than the current value of the properties. Last year’s figure was 9.9 percent.

While Trenton’s difficulties may be hard to ignore, they vividly broadcast trends echoed in data from communities throughout the state.

In Freehold, foreclosure filings in June were up 90 percent from a year ago. Some 359 homes were declared in mortgage default, awaiting sheriff’s sale or already taken by banks and investors, compared to just 219 for sale; Compared to most of the state, Jersey City has a booming housing market, with the most recent data showing sales up 26 percent in May from a year earlier. But foreclosure filings were up 33 percent in June, and bank-owned or foreclosure-threatened homes accounted for 72 percent of RealtyTrac’s current listings;

Vineland saw foreclosures jump 125 percent, and homes in the process or already taken by banks outnumber others for sale. Those distressed properties sell for an average of $94,950, compared to $156,000 for other housing;

Morristown’s foreclosures also are up, but the aggregate number of homes being sold by regular means still tops the bank-owned properties. The town’s problem lies more in the $152,500 price gap between the two classes, with year-over-year sales down 35 percent in May;

Flemington has an equal number of market and distressed homes available, but none of the latter have sold since January, even as new foreclosure filings have more than doubled from a year ago;

Banks and investors have already taken 1,129 homes in Irvington, and the 829 currently in progress are more than the total units owned by the township’s housing authority. Yet of the 81 sales in the first half of this year, just 11 bank foreclosures back on the market, while another 27 were short sales allowing homeowners to walk away from underwater mortgages;

Cherry Hill saw foreclosures rise 40 percent in June from a year ago, while home sales fell 12 percent. Unlike some communities, though, the average price for distressed properties was just 16 percent below the median;

In Phillipsburg, home sales dropped 73 percent from a year ago, and the average sale price of a foreclosed home, $52,500, was just slightly more than one-third of the market median.

Not all the statewide news is bad. CoreLogic did find home prices here rose 4.1 percent during the past year. Still, the national increase was 7.5 percent, so New Jersey ranked 33rd among the states and District of Columbia.

Yet Trenton does not share in such tepid positive signs, even those from seemingly similar markets.

Trenton’s median home price is only a bit less than those of Newark and Paterson, but it is heavily weighed down by those 2,473 foreclosure properties. Even before the new surge in foreclosures, Trenton’s home-ownership rate for the five-year period ending then was 40.5 percent, compared to 66.2 percent for New Jersey as a whole, according to the Census.

Those foreclosed homes that are being resold in Trenton are going for an average of just $40,000, according to RealtyTrac, and their prices have remained below $50,000 for at least seven months, less than a third of market price.

“That is a very large disparity,” said RealtyTrac Vice President Daren Blomquist, and unusual for its persistence without normal monthly market fluctuations.

Many Trenton homes fit the pattern of places like Detroit, “older properties, smaller properties, close to the city center that are less desirable,” he said. But the large overhang of foreclosed and threatened properties extends into neighboring Ewing, which has 808 of those but just 364 current RealtyTrac sale listings.

Some people believe the local market has bottomed out and is beginning to rebound. Albin Garcia of Garcia Realtors in Trenton said the RealtyTrac numbers reflect a working through of past problems, not future prospects.

Despite the the continued reluctance by most banks to lend in the city, the trend “across the board” in Mercer County “has been very hopeful, it’s coming up,” Garcia said. That applies even to the Trenton neighborhoods of Villa Park and Franklin Park, he said.

The very low prices for Trenton’s foreclosure properties in recent months reflect a move by some banks to finally unload their built-up inventory of seized houses, many more suited for demolition than re-sale, he said.

“You’re seeing properties selling for $21,000, $22,000, $23,000,” Garcia said. At present, he said, there are no prospects of large-scale redevelopment.

So what the future holds for those bargain-basement homes, or their lots, is uncertain. But Garcia said he is witnessing a return to the era immediately before the housing bust. Without competition from big developers, small companies and entrepreneurs are again looking for values in the city, he said.

“That was the trend back in 2004-2008, when we had small developers buying up a few properties and doing a beautiful job” rehabilitating them, Garcia said.

He finds hope in legislation, S-1131, sponsored by state Sen. Shirley Turner (D-Mercer), that would provide no-interest second mortgages for police, firefighters, public school teachers and sanitation workers.

Robert Prunetti, president of the Mercer County Chamber of Commerce, pointed out that Area Development Site and Facility Planning magazine is bullish on the Trenton area’s prospects, rating it 13th among 379 metropolitan areas for economic and job growth.

“With companies growing and expanding their reach in this region such as ( loan servicer) Cenlar FSB in Ewing, as well as the redevelopment of the old General Motors plant into mixed-used development, this area will continue to flourish,” Prunetti, a former Mercer County executive, said in a statement.

Turner has also pushed legislation for state aid to help Trenton rebuild its police force. In July, the department announced it would use a federal grant to send 40 new recruits for training this fall, replacing some officers lost to layoffs or retirements.

But Hughes said the city faces another challenge, as New Jersey’s public sector has hemorrhaged jobs. Many state government positions vanished with the recession and have not returned, a critical loss of wages for a place like Trenton with a private sector tied to government activity and state employee customers.

“Those opportunities are gone,” Hughes said. “There are a lot of empty spaces in those (state) parking lots.”

Instead, Gov. Chris Christie’s administration has invested in private ventures like the Revel casino in Atlantic City, which only opened in 2012 but just announced its Sept. 10 closing, the fourth of the city’s casinos to go under this year. Bucking the national trend but mirroring the casino industry, housing prices are trending downward in Atlantic City, and analysts see no bottom in sight.

Although safety issues may trouble Paterson, it has “a large and vibrant immigrant community, from diverse sources, and it’s close to the New York job market,” so its hopeful outlook compared to Trenton is understandable, Hughes said.

Whether in Freehold, Trenton or Atlantic City, the common factor hampering New Jersey’s housing markets is the slow recovery in every other key sector, according to Peter Reinhart, director of the Kislak Real Estate Institute at Monmouth University.

“We’ve got a slow growth, slow jobs economy now,” said Reinhart, former president of the New Jersey Builders Association.

Rebuilding from Hurricane Sandy provided a boost in some communities, but some property owners have found the financial burdens too great and have either sold or are hanging on with minimal reconstruction, he said.

“You drive along side streets in Sea Bright and you see what I call the Jack-o’-lantern effect,” Reinhart said. “One house is up on stilts, the next house is still at street level, the next on stilts, the next down.”

Homeowners who have not received government assistance may be out of luck, In n the wake of the recession, banks have been tighter with money. Meanwhile, many potential buyers are either saddled with debt or cautious about taking it on, he said.

“Millennials, first-time buyers are very slow to come into the market, maybe because of the tight job market, maybe some with student debt,” Reinhart said. “People like me, who would think about selling for retirement, they’ve seen their household wealth decline.”

There have been shocks to the housing market before, Hughes said, but this downturn has dovetailed with a change in attitudes as well as fortunes.

In 1999, when 31,976 construction permits for new housing were issued in the state, 25,129 or 78.6 percent were for single-family homes, he said. Last year, as the market finally rebounded, the total climbed back to 24,199 — but only 10,377 were single-family units.

“Up until the Great Recession, housing was the super piggy bank, the investment that couldn’t go wrong,” Hughes said. “Now people know it can.”

Members of that millennial or “echo boom” generation born from 1977 through 1995 “recognize that home ownership can restrict their mobility.” he said. “If you have to move 300 miles for a new job, it’s difficult if you have a mortgage.”

Similarly, post-war baby boomers starting to wind down their careers are realizing “retirement may be a rental” rather than another house, he said.

But for Reinhart, the slow recovery of housing markets in New Jersey and some other regions “is not a problem with the economy, not a problem with jobs, it’s a problem with bad loans.”

Nationwide, two-thirds of the mortgages already foreclosed upon or in process were issued in 2004-2008, as the housing bubble was fully inflating and then popping, Reinhart said. In New Jersey, the figure is even higher, at 71 percent.

While urban areas are filled with horror stories of predatory loans and fraudulent mortgages issued to naïve borrowers at unsustainable terms, Reinhart noted that New Jersey had high housing costs even before the bubble.

As home mortgages became overpriced, buyers “across the spectrum” made bad deals, he said. “There were a lot of wealthy people who got into loans they can’t afford.”

In his view, the cleanup of those bad debts was delayed in December 2010 when tstate Chief Justice Stuart Rabner, acting in response to foreclosure fraud cases here and elsewhere, ordered major mortgage lenders to demonstrate that their processes are clean.

Once they reformed their practices, delayed foreclosure cases flooded the state courts, Reinhart said. But he acknowledged that the new cases mean those borrowers were unable to get mortgage modifications in the intervening years.

Federal aid programs “did some good, there would have been more foreclosures without them,” but did not match the need, Reinhart said. Those factors contributed to lagging demand, and continuing foreclosures, in apparently well-off New Jersey suburbs, he said.

Still, New Jerseyans should take heart, Reinhart said. Although housing problems have persisted here, even the hardest-hit communities have never been bad off as Las Vegas, where at one point one of every 60 housing units was somewhere in the foreclosure process, he said.

But he agreed with Hughes that the housing market is changing as home ownership drops. More than 8 million Americans have lost their homes during the past seven years, and relatively few are in position to buy again, Reinhart said.

___________________________________

NJ Spotlight, an independent online news service on issues critical to New Jersey, makes its in-depth reporting available to NewsWorks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.