Homegrown Middle Class: How to design a milestone

To John Kromer the city’s persistent poverty is best tackled at the neighborhood level. In a four-part series of commentaries Kromer, an urban housing and development consultant and former city housing director, is exploring different policy interventions the next administration can deploy to reduce poverty, stabilize neighborhoods, and finance anti-blight work. In this final installment, Kromer describes how a new policy for Philadelphia neighborhoods could be organized during the coming months for implementation in 2016. Imagine this as look into the near future, if Philly seizes the opportunity.

In a ceremony held at the White House in January 2016, shortly after the inauguration of Philadelphia’s 99th Mayor and shortly before President Obama’s final State of the Union address, the President announced the signing of an agreement to launch a comprehensive anti-poverty policy for Philadelphia neighborhoods, with the initial phase of activity to be implemented during the coming four years.

Obama Administration Place-Based Initiatives:

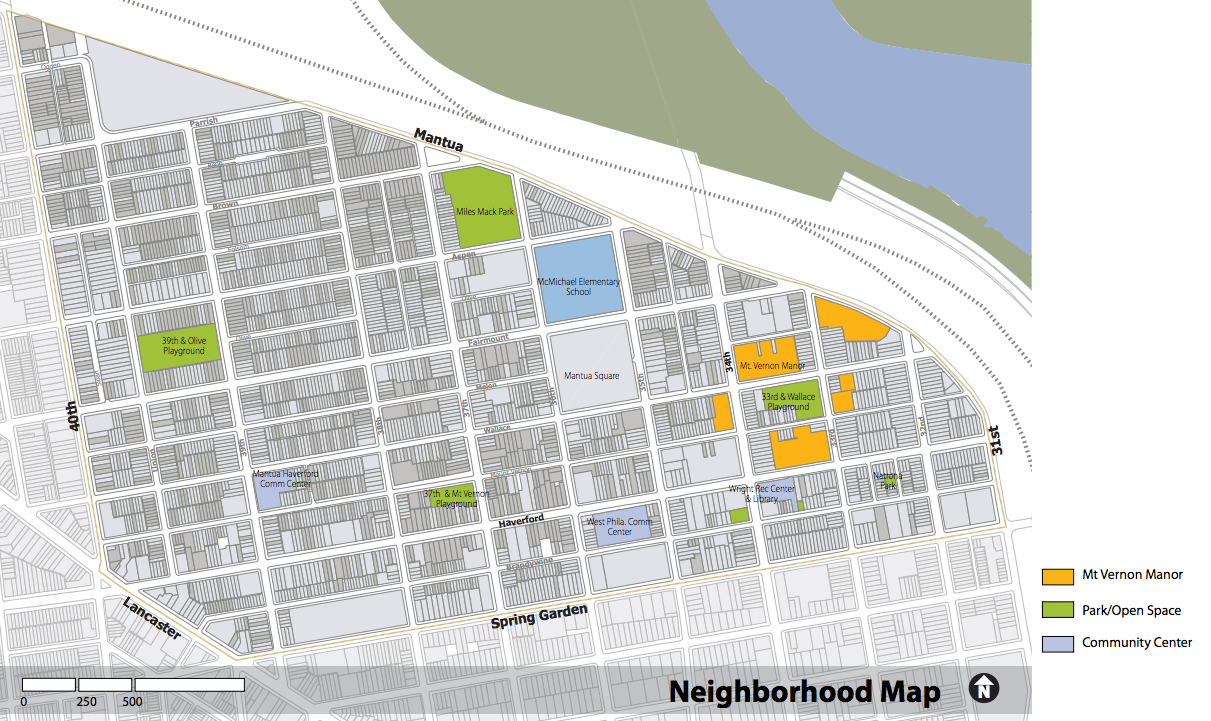

Choice Neighborhoods: Mixed-income housing development on former public housing sites is accompanied by coordinated development and supportive service activities in a surrounding target area. Philadelphia’s Choice Neighborhood “Transformation Plan” target areas are located in Mantua (map above) and in North Central Philadelphia in the vicinity of the Temple main campus.

Promise Neighborhoods: In this program, inspired by the Harlem Children’s Zone concept pioneered by Geoffrey Canada, neighborhood schools and service providers implement a portfolio of “cradle to career” services to help ensure that children will have the best prospects for success in completing their education and beginning productive careers. In 2010, the Universal Companies was awarded a planning grant for a Promise Neighborhood program in Grays Ferry and Point Breeze. Although not subsequently selected to receive a federal implementation grant, Universal and the School Reform Commission agreed to implement the program design specified in the plan document.

Promise Zones: The federal government works with community constituencies to support the implementation of strategies designed to increase economic activity, improve educational opportunities, reduce crime, and leverage private investment within a designated target area. Philadelphia’s Promise Zone includes some of the West Philadelphia communities expected to be most directly affected by current and anticipated institutional development.

Joining the President at this announcement were Governor Wolf, former Mayor Nutter, Philadelphia’s newly inaugurated Mayor, Philadelphia’s City Council President (spoiler alert: it’s Darrell Clarke), the presidents of Drexel, Penn, and Temple, and others.

Why did the President enthusiastically buy into this new policy? Because, in mid-2015, a group of Philadelphia leaders had asked him to support a concept that did not require new legislation or a commitment of new federal funding and that would direct available resources to the Philadelphia locations that his administration had previously approved as target areas for three signature programs: Choice Neighborhoods, Promise Neighborhoods, and the Promise Zone (see sidebar for program descriptions).

But what was even more important, from the President’s perspective, was that this initiative represented a dramatic departure from the traditional urban-aid model that had been a mainstay of federal policy for nearly a century. Under past administrations, the federal government had made a practice of awarding large grants or tax credits to city governments and urban development ventures, and these awards had been expected to fund most or all program or project costs, with little or no leveraging of other resources. Under this traditional policy model, municipal governments or public authorities agreed to administer the funding and comply with an array of associated regulations.

Philadelphia’s approach was fundamentally different from these past practices. The Philadelphia policy represented a true collaboration, in which existing federal funding would be complemented by substantial commitments of financing and other resources from a group of local partners who would collectively take responsibility for meeting performance goals and producing quantifiable positive outcomes without reliance on a high level of federal oversight.

The Philadelphia partners had the capability to work constructively with federal agencies to make this approach successful; and, if the approach did prove successful, as anticipated, this initiative could be replicated more broadly and might become the model for a 21st century policy for U.S. cities.

A Transition-Period Opportunity

During the period between the November 2015 mayoral election and the January 2016 White House announcement, the Nutter Administration had worked closely with the newly elected Mayor, mayoral transition-team members, and the Council President to finalize the agreement in preparation for the January event.

Why would a lame-duck mayor devote a substantial amount of his senior administrators’ time and attention to crafting a plan that would not be implemented until after he left office? Because his leadership role in designing an innovative, high-profile approach to address the nation’s greatest urban challenge would be widely recognized as a major “legacy” accomplishment of his administration, because this policy initiative would be publicized nationally before he left office, and because this achievement would position him well for his next career move.

Why would an incoming mayor agree to sign on to a policy initiative that, in large part, had been designed by the Nutter Administration and others prior to the November election? Because this initiative was consistent with pledges that the new Mayor had made as a candidate and because the administration would not have to find new funding to support its role in implementing the policy.

The new policy was also consistent with neighborhood program initiatives that returning City Council members had supported during the previous administration and with the views that new Council members had expressed during their campaigns. As important, the policy would not require Council legislation to reallocate existing city funding or reduce commitments to existing programs and services.

Why Philadelphia?

There was a particularly good reason why the Philadelphians who approached President Obama in mid-2015 had been able to make a strong case for the selection of this city as the site for a major anti-poverty initiative. In Philadelphia, three prominent academic institutions—Drexel, Penn, and Temple—had already made major commitments to promote human capital development in off-campus communities that had also been designated as Choice/Promise target areas by the Obama Administration. The institutions’ level of involvement in these communities was, in some respects, unprecedented in scope and was consistent with three principles that had contributed to the success of Penn’s West Philadelphia Initiatives during the 1990s: provide leadership at the university president’s level; don’t organize programs that are dependent on federal or state government support; and invest funding and staff resources in activities that are responsive to the self-interest of both the institution and the community.

Although the potential for so-called “anchor institutions”—city-based academic and health care institutions—to serve as catalysts for urban neighborhood revitalization had been studied and discussed for years, there was no other U.S. city in which multiple anchor institutions had made and were acting upon such broad commitments to advance equitable development and human capital development in geographic areas as large as the Philadelphia communities in which Drexel, Penn, and Temple were engaged. These institutional commitments were consistent with the goals of the Obama Administration’s Choice/Promise programs, as well as with the mission of the Mayor’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity, created by Mayor Nutter in 2013.

Well before 2015, a substantial amount of planning to guide public and private investment in the Choice/Promise communities had already been completed or was under way. In addition, two respected community development intermediaries, the Philadelphia Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and The Reinvestment Fund (TRF), had already been providing financing and technical support for housing, retail, and community facilities development in the Choice/Promise target areas, as well as for neighborhood schools, and community-based supportive service activities, and they were well positioned to expand their roles in these communities.

Based on these considerations, the Obama Administration recognized that the selection of Philadelphia as the location for a major anti-poverty initiative would amount to much more than a new collaboration; it would demonstrate, for the first time, a way in which institutional engagement in urban communities, coordinated with public and private investment that was facilitated by–but not dependent on–the federal government could be elevated to a new level and produce positive results on a large scale.

Serendipitously, the first results of this policy could be showcased to people visiting Philadelphia for the Democratic convention that would open in July, six months after the policy-launch announcement.

Self-Interest and Public Interest

During the months leading up to the November elections, the Mayor’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity had hosted a series of meetings to complete a draft of the policy. The approach proposed as the basis for this policy appealed to representatives of the three universities and other participants because it didn’t require them to share any of their funding with the city (or any other party) or to relinquish control over the management of current and proposed activities. They had simply agreed that they would work together to advance a common mission: pursue the most effective ways to reduce poverty within the Choice/Promise target areas by providing community members with substantially improved access to education, training, and supportive services that would increase the prospects for success in the 21st century workforce. In support of this mission, the participants agreed to work together to secure White House buy-in and related support for the policy, leverage new funding to broaden the impact of their activities, and establish performance measures that would become part of an annual independent performance monitoring of the policy.

These organizations participated because the collaborative approach had the potential to leverage more resources that would enable them to accomplish more of their goals and produce results on a larger scale. For example, the Philadelphia School Partnership and the School Reform Commission agreed to give first priority consideration to supporting school transformation opportunities associated with schools located within the Choice/Promise target areas. Representatives of the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA) agreed to give priority ranking to proposals for Low Income Housing Tax Credit financing and tax-exempt bond financing for development ventures located in the Choice/Promise areas. With PHFA, the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development agreed to subsidize financing and provide rental assistance funding to support small (one- to four-unit) moderate rental housing rehabilitation ventures located in the Choice/Promise areas. These commitments were relatively easy to make because, while supportive of the new policy initiative, they didn’t require fundamental changes in existing policies and programming.

By aggregating their current activities, associating them with an overall anti-poverty policy “brand,” and agreeing to collaborate on program planning and performance evaluations, the participants improved their prospects for attracting additional funding resources.

For example, some of the academic institutions’ existing program activities in the Choice/Promise target areas were already being supported by grants from national foundations that had a particular interest in advancing anchor-institution initiatives in urban neighborhoods. Even in a worst-case scenario, these and other foundations would be likely to sustain current funding which, combined with the institutions’ own funding for these activities, was already substantial. But it wasn’t unreasonable to imagine that national foundations might be even more interested in being recognized as major supporters of the decade’s most ambitious anchor-institution initiative—one that started in the Oval Office.

Although Drexel, Penn, and Temple didn’t change their position regarding payments in lieu of taxes, or PILOTs (they continued oppose them) their representatives suggested that the funding they would be spending on university-administered activities in the Choice/Promise neighborhoods–whether supported with foundation grants or internally financed–should be regarded as equivalent to PILOT payments, in that these expenditures supported community access to education, health care, and human services that, in a wealthier municipality or in some other states, would have been funded by taxpayers.

What the White House Brought

The Philadelphia participants were successful in convincing the President to agree to three major executive actions in support of the new policy.

- Administer Philadelphia’s Choice Neighborhood funding as a block grant. The current process for administering federal Choice Neighborhoods funds requires a lot of interaction between Philadelphia development agencies and managers at HUD headquarters in Washington. As a result, everything takes longer. By contrast, HUD Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funding, awarded annually to the city’s Office of Housing and Community Development (OHCD) following review and approval of a funding application, does not include any requirement for HUD to review and approve program activities as they are implemented (although the programs are routinely monitored for compliance with federal regulations). If the Choice Neighborhoods funds were to be block-granted like CDBG funds, the city could achieve results could more quickly and efficiently while continuing to honor commitments to HUD, the Housing Authority, and public housing tenant councils.

-

Draft and execute a four-year partnership agreement between HUD headquarters, the City of Philadelphia, and the Philadelphia Housing Authority. Although the relationship between city agencies and PHA is, in some important respects, much stronger than it has been in years, the drafting and approval of a multi-year work plan authorized by HUD could become the basis for a more structured and more productive city/PHA collaboration.

With the participation of HUD’s Deputy Secretary, the city and PHA could design and formalize a four-year work plan that would be the basis for coordinated actions to support activities in the Choice/Promise target areas. -

Change the CDBG calendar. The federal fiscal year begins in October, but the City of Philadelphia waits until the following spring to apply for its share of the Community Development Block Grant funds and other housing funds that are included in the federal budget. In this way, the CDBG program year schedule is made to coincide with Philadelphia’s July-to-June fiscal year. But it’s not really essential for the HUD funding to be synchronized with the city’s fiscal year; the city has always had the capability to administer grants involving program schedules that differ from the municipal fiscal year.

If, with federal approval, the City were to move the start of the CDBG program year six months earlier, from July to January, HUD funding would become available sooner and could be used more efficiently to address urgent priorities. This schedule shift wouldn’t be a radical change; many other municipalities and counties currently operate on a January-to-December CDBG program calendar.

But this schedule change could also provide a substantial amount of public-sector funding for the neighborhood policy initiative. During the first year in which the change would take effect, the last six months of the old program calendar (i.e., January to June) would overlap with the first six months of the new program calendar, and Philadelphia would get a one-time bump in HUD funding. How big a bump? It would amount to half the CDBG award and half of the other federal housing funds made available to OHCD—it might provide $25 million or more of new funding, most of which could be committed to supporting activities in the Choice/Promise target areas and could serve as a local match to leverage other funding.

Time to Get Ambitious

Some Philadelphians have a tendency to think small—if you said “President” to them, they’d be thinking “Darrell Clarke.” But this year, we have an opportunity to think and act a lot more ambitiously. I’ve spoken about the sequence of events summarized above with some people who have the ability to communicate directly with President Obama or senior members of his administration. They’ve told me that, under certain circumstances, getting a meeting at the White House next January and convincing the appropriate parties to actively support a neighborhoods policy similar to the one I’ve described would be doable—not a guaranteed slam dunk, but doable.

For the sake of enriching the current campaign-season dialogue, let’s just assume that this expectation is realistic and that the successful candidate for Philadelphia Mayor could get a meeting at the White House in January. In anticipation of this event, what’s the best policy proposal that could be organized this year and presented in January as the solution to Philadelphia’s biggest challenge? Is it the one described above—or is it something even better?

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.