A new Holocaust mural on the Parkway tells a story of displacement in 28 languages

“Lay-lah Lay-lah,” by artist Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson, uses ancient texts to connect the historic atrocity to a range of communities and underscore a shared humanity.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza on Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway now has a mural about the Holocaust.

But it may not be obvious to the casual passerby.

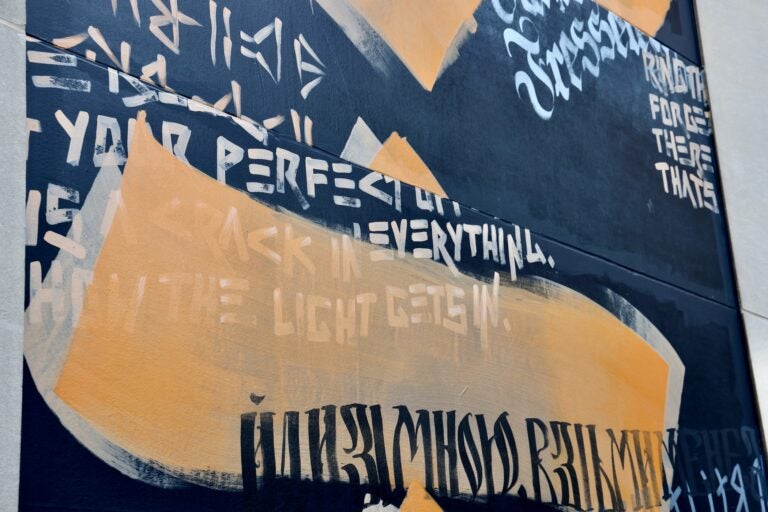

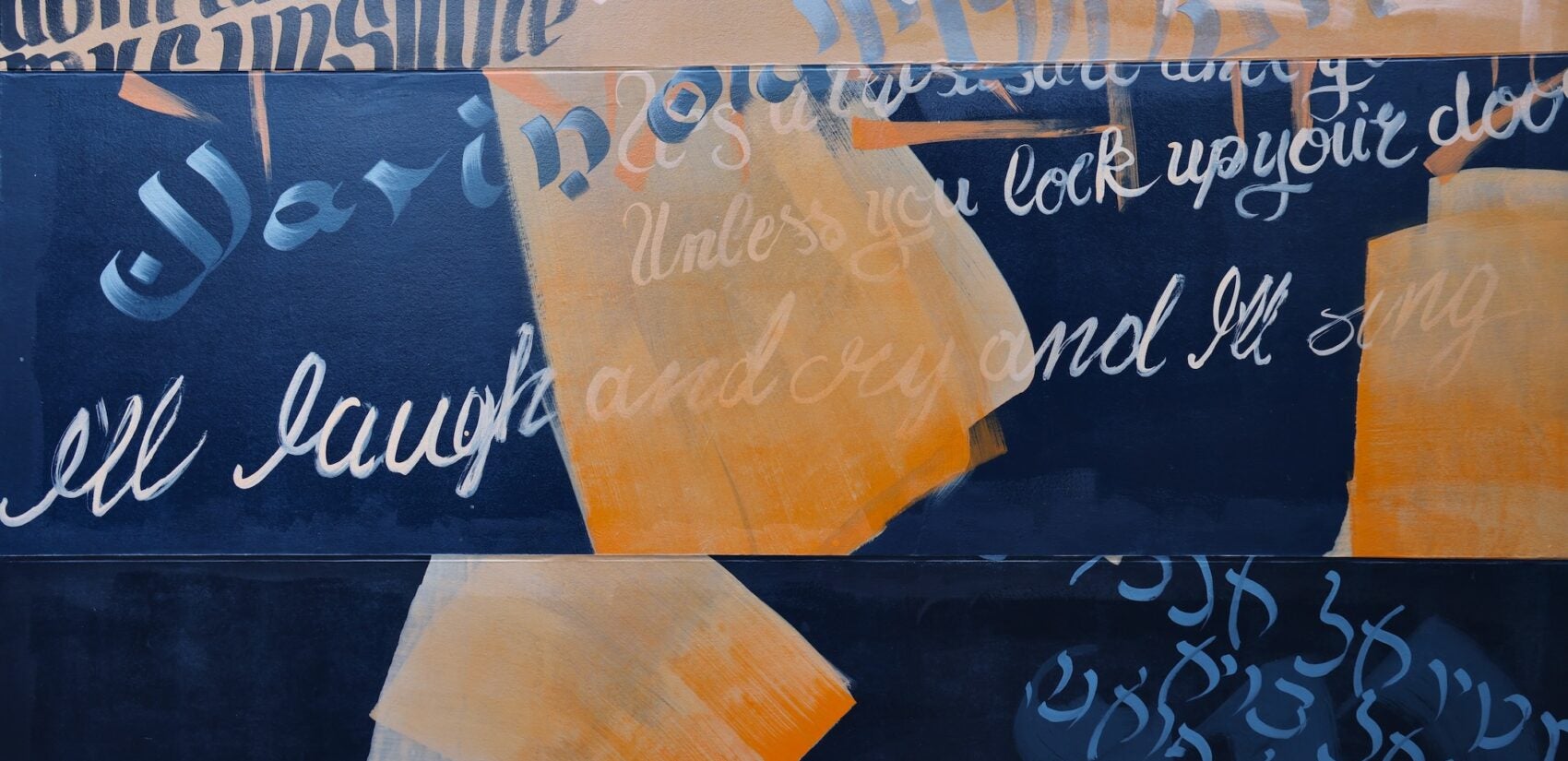

The eight panels of “Lay-lah Lay-lah” by the Berlin-based artist Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson, painted mostly in muted oranges and blacks, towers 28 feet high and stretches about 100 feet across the eastern wall of the Verizon building at 16th and the Parkway.

The content of the mural is mostly disjointed fragments of text, some of which will be illegible to most people. There are 28 languages represented, written in 17 different scripts. Several are dead languages no longer spoken or written by any population left in the world.

Ponizovsky Bergelson said “Lay-lah Lay-Lah” is about the global displacement of Jews following World War II.

“That’s why you see interruptions, and texts written over each other and ruptured,” she said. “It’s mimicking the idea of displaced identities that have to layer new languages, new texts, new cultural identities over and over again once moving to a new location.”

Each snippet of text comes from someone in Philadelphia. Working with Mural Arts Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Holocaust Remembrance Foundation, Ponizovsky Bergelson held community engagement sessions during which she asked people to recall a line from a song, a story or poem from their childhood that was handed down by family elders.

She then researched the origins of those lines to find out what original form they took, and in what script.

“There is a prayer, for example, in Hebrew and 5,000 years old. I would go and research how people were writing at that time and then I would use that typeface,” Ponizovsky Bergelson said. “We have here Aramaic, ancient Babylonian, all kinds of languages which are no longer spoken today.”

“There are also contemporary alphabets there,” she said. “For example, American songs from the ‘70s were adapted to the style that was popular at the time here in the U.S.”

“Lay-lah Lay-lah” is now a prominent part of the Parkway landscape, occupying an enormous wall on the procession from LOVE Park toward Swann Fountain. It acts as a backdrop to elements of the Holocaust Memorial that have been in the plaza, including Nathan Rapoport’s “Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs” statue and six panels explaining historic topics like “Nuremberg Laws,” “The Master Race” and “Totalitarianism.”

Eszter Kutas, the executive director of the Holocaust Memorial Foundation, was not looking for Ponizovsky Bergelson to reiterate those concepts, but rather design a mural that would expand the conversation around the Holocaust.

“I’m humbled and overjoyed at the same time. It came out better than any of us expected,” she said. “The topic of displacement and the aftermath of the Holocaust is not something that is already present with other content here. She tackled a topic that is really so relevant for our times today.”

After World War II, approximately 11 million people were displaced in Europe, many scattering around the globe, including America.

Kutas says evoking displacement and migration can connect the legacy of the Holocaust to other communities in Philadelphia, even ones that might not have been directly impacted by the historic atrocity.

“There’s a lot of text in Hebrew and Yiddish and English, but there’s also over 20 other languages present here,” she said. “Those stories hail primarily from Europe but also from the Americas, from Asia, from Africa. It shows the true fabric of our city, how many minorities went through displacement and resettled here in Philadelphia.”

Kutas was also struck by how soft the mural is, using gentle phrases typically told to children.

“There’s a sweet element to having songs, prayers, and lullabies,” she said. “It’s a nod to what has survived, despite all odds, having been passed down generation to generation.”

The way “Lay-lah Lay-lah” uses text that is both evocative and abstracted is unlike any other mural in Philadelphia, said Mural Arts Philadelphia director Jane Golden. She and Kutas knew they had to tread carefully in selecting Ponizovsky Bergelson to make a public mural about such a weighty historic event.

“There’s a great thread that connects us all as being human,” Golden said. “In our world now there’s something lost that deals with our common humanity. Through her art she’s holding out her arms and asking people to come in.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.