Historical Delaware black school becomes state landmark

Harry Crapper stood on the grounds of his childhood school and sang the words to the gospel song “I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired.”

To the Dover resident, the religious lyrics are motivational, and encourage him to pick himself up from hard times. The song hits home to Crapper, who has been one of several individuals fighting hard to make the Richard Allen School in Georgetown a historical landmark.

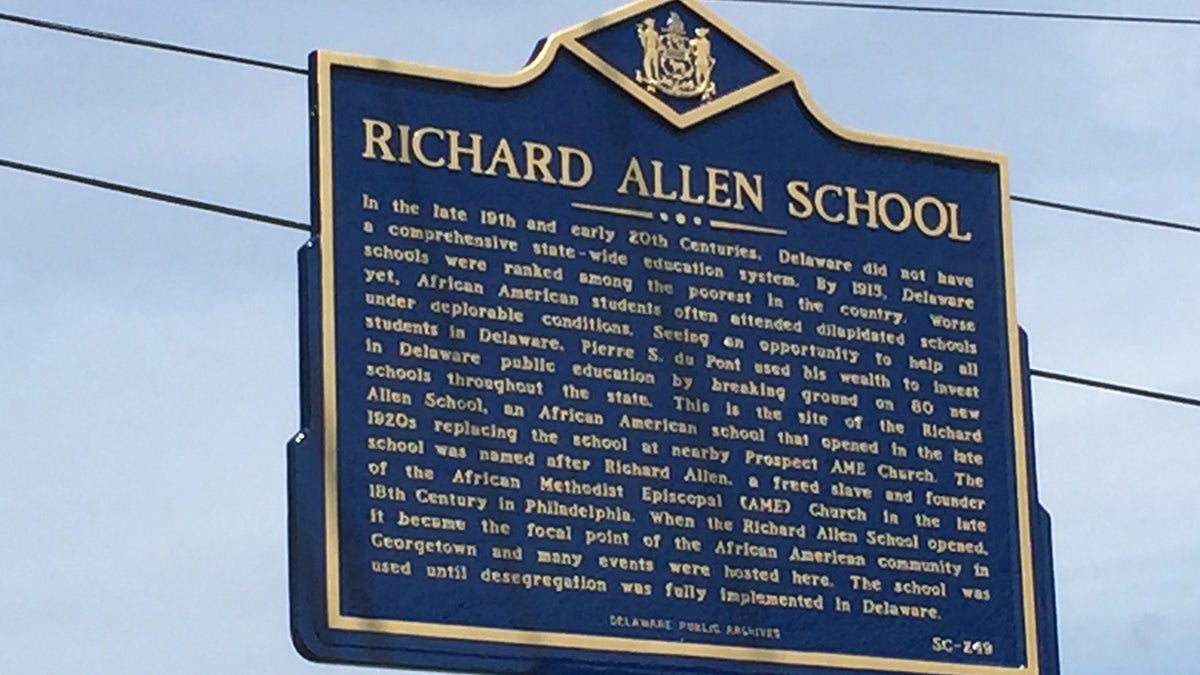

Friday, their efforts were realized when the Richard Allen Coalition celebrated the unveiling of a historical marker outside the historically black school.

“We have been working on this a long time for about two years,” said Crapper, treasurer and co-founder of the coalition. “We’ve been up, we’ve been down and we kept on going.”

Historic beginnings

The Richard Allen School, which opened in the 1920s, was funded by philanthropist and industrialist Pierre DuPont.

It was built in a modern brick structure, and was intended to serve grades one through six. Prior to its opening African American children attended an aging all-black school in the Prospect AME Church a short distance away.

When schools in the U.S. became integrated it served as a kindergarten and an elementary school. It’s last incarnation was as an alternative school until 2010. It was after its closing that the Richard Allen Coalition was formed in an effort to inquire the school as a historical landmark and museum.

A new role

Jane Hovington, president and co-founder of the coalition, never attended the school, but when she learned about its history, she set out to make it heard. With the help of Sen. Brian Pettyjohn, R-Georgetown, Rep. Ruth Briggs-King, R-Georgetown, and the Delaware Public Archives, the coalition were able to get a historical marker for the school.

“There’s so much history here, our desire is to document it and have it on display,” Hovington said. “So much of that history is in boxes and closets.”

Honoring Richard Allen

The school is named after Richard Allen, who was born into slavery in Philadelphia in 1760, and was later bought by a Delaware farmer, Stokeley Sturgis, along with his family.

At age 17, he bought his freedom and in 1816 went on to found the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first national African American church in the U.S.

Allen became a notable civil rights leader, and his church Bethel Church was one of the stops during the Underground Railroad.

“I’m quite sure Richard Allen and Pierre DuPont are smiling in heaven right now,” said Darrell Melvin of Georgetown, who attended the school between 1967 and 1971.

“It means a lot to the African American community.”

Thoughts of South Carolina

An AME church in South Carolina faced tragedy Wednesday when a white man shot and killed nine members during a meeting.

“When you look at the incident that just happened, we don’t need those incidents anymore,” Melvin said. “You can’t change anything in the past, but you can change the future. We want to make a difference in our community and see the kids change.”

Bernice Hintin of Milford said the shooting reminds the community not to stay complacent, and continue the work that Allen was passionate about.

“It tells us there’s more work to be done, and going back, being here and going through this event today is part of that cycle,” she said.

Remembering good times

During the event, former students of the school celebrated the event and remembered their experiences at the school.

Crapper has joyful memories of playing baseball on the first black baseball team in Georgetown. He said he used to play every weekend and the neighbors nearby made sure he and his friends behaved themselves.

“They used to break bad on us, ‘Don’t bust these windows!’” Crapper said

Hintin who attended the school from 1955 to 1961, said she enjoyed the quality time she had with her teachers. The school had three teachers who were divided into three grades.

“It was awesome being in the same teacher’s class for two years in row because we got a lot from those teachers,” Hinton said.

“We picked up manners, not just arithmetic and math, we picked up discipline, we learned everything we needed to better ourselves.”

One of the oldest surviving former students, Eunice Richardson of Reading, said she owes everything to the education she received at the school.

“One of the most important things I learned for myself was that anything I wanted to do in my life I had the opportunity to work hard and succeed at whatever I wanted to do,” she said.

“If it had not been for this school here many of us would not have received a good education. It carries a history of the starting point in our lives.”

Crapper said the students didn’t have the best quality books and stationary. They received hand-me-down books from a school for white children, and often the pages were torn or missing.

“Through all of that we had judges leave here, doctors, lawyers, because you had good teachers. It has done great things for us,” Crapper said. “This was my foundation of becoming a good man.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.