Historic African American visions of a life of freedom and elegance

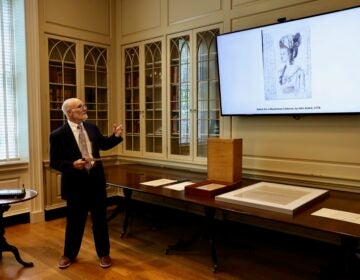

The Library Company of Philadelphia opens an exhibition of African American history told solely through African American artifacts.

A photo of an unidentified young African American woman is deeply creased as if it were folded and carried around by someone who valued it. It is part of an exhibit at the Library Company of Philadelphia called "Negro Pasts and Afro-futures." (Emma Lee/WHYY)

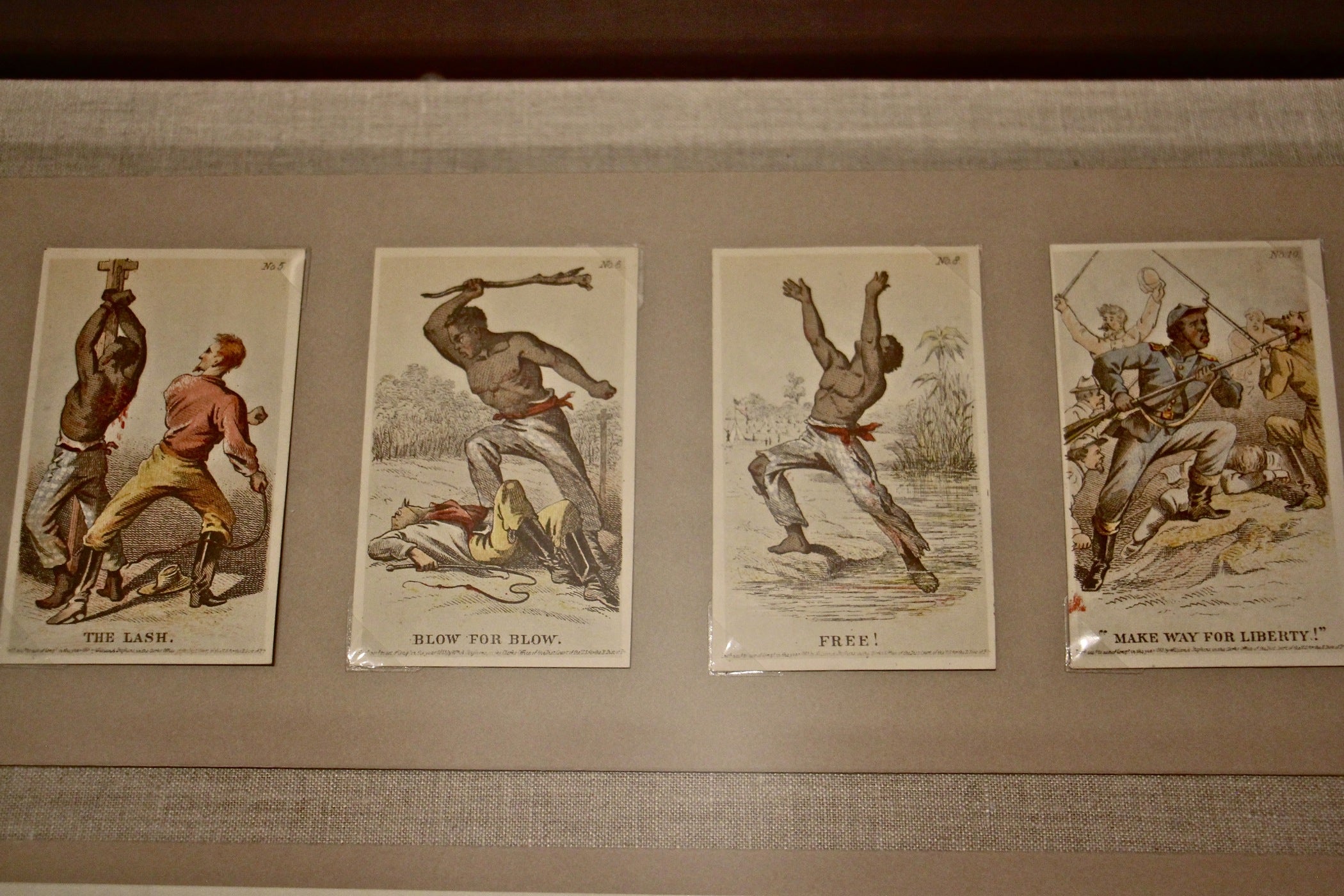

Despite a long culture rich with tradition, it can be hard to find materials that show how African-Americans viewed themselves throughout history. In the early days of the United States, black people were often described by white people — sometimes sympathetically, often not.

“From Negro Pasts to Afro-Futures,” an exhibition now on view at the Library Company of Philadelphia, is an assemblage of historical postcards, letters, sheet music, drawings, books, and prints that African Americans used to remember their own past and envision a future for black America.

“When people think of African American in the 18th and 19th centuries, they think of slavery, caricature drawings, and the harsh circumstances African Americans had to endure,” said co-curator Jasmine Smith, a specialist of African American material at the Library Company. “This exhibition showcases them in a positive light.”

Near the entrance of the exhibition is a print from 1872 depicting seven African Americans newly-elected to Congress, from mostly southern states.

It’s the only known image of that first group of black senators and representatives elected at the tail end of Reconstruction. Even more interesting: it was produced by Currier and Ives, the publisher of popular cards and prints. It was meant for a mass audience.

“It was to be sold, geared toward middle-class, African Americans to display and show there is representation fighting for what they believe in,” said Smith.

“Negro Pasts to Afro-Futures” comes exactly 50 years after a 1969 Library Company exhibition displaying works describing African-American history. That exhibition was partly in response to academic cries for more historic materials portraying black America. However, it featured many writings and illustrations created by white people.

The Library Company — the oldest library in the country, founded in 1731 by Ben Franklin — has been collecting items related to African Americans since 1773, when it acquired a book by the enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley.

In the mid-20th century the institution began to more aggressively and proactively acquire African American artifacts. This exhibition of black history, shown through products created and consumed by African Americans, is a corrective to the Library’s prior exhibition.

The oldest object in the room is an Ethiopian Coptic Christian book from 1682, written in the native Ge’ez, an ancient and largely dead language that was kept solely for religious applications. The illustrated text, “The Homilies of Michael,” is an account of Archangel Michael, the heavenly protector of mankind from Satan.

At more than 300 years old, it is a direct connection to native African Christianity, a religion distinct and unique from its Western counterparts. It is also an impressive piece of material culture, with stunningly vibrant color illustrations.

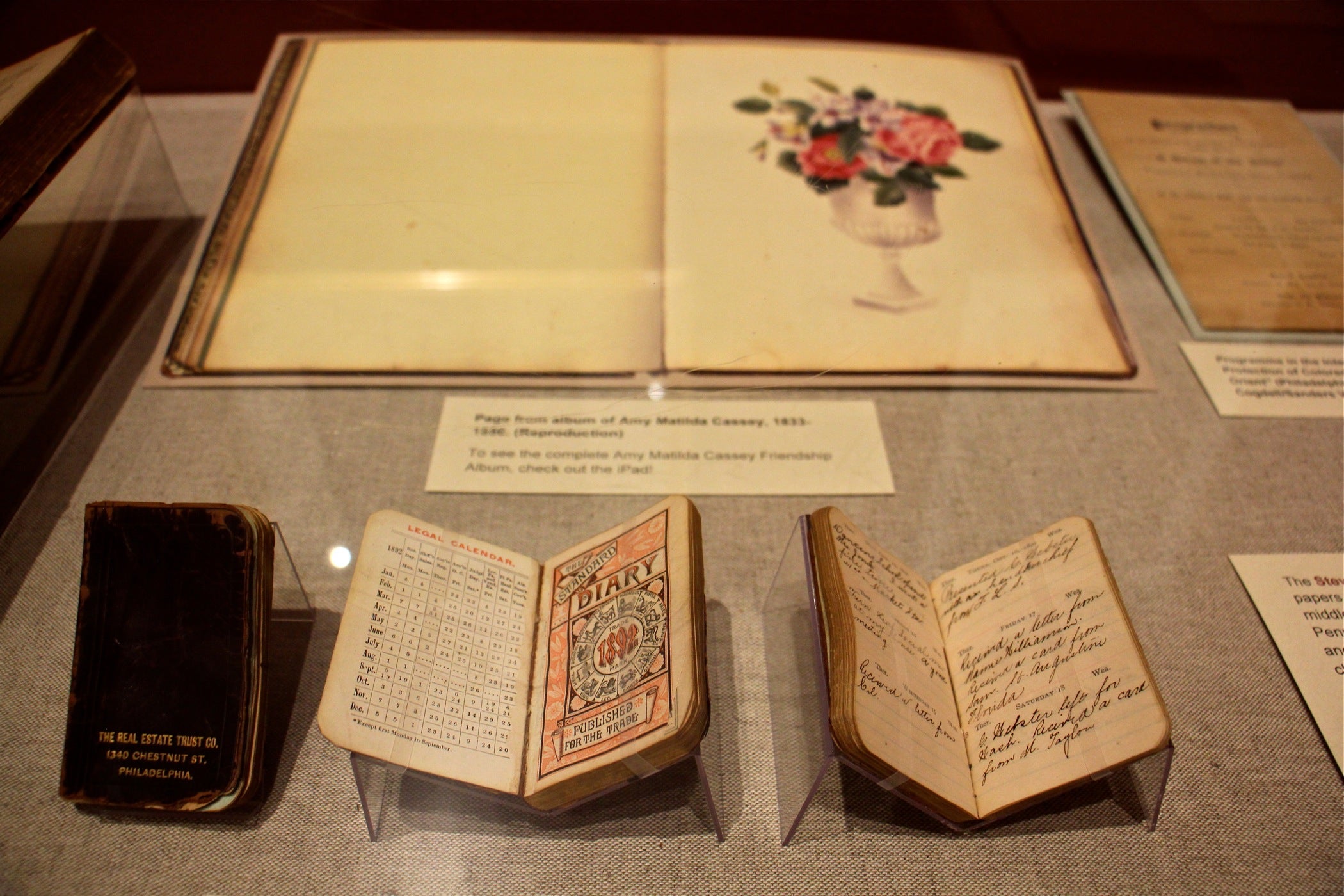

The exhibition is divided into five sections: politics, religion, arts, race, and ephemera. The last contains materials mostly from the archive of the Steven-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning family, a mixed-race legacy in Philadelphia that extends back to 1760.

In that collection are friendship albums, a social tradition unique to the African-American community. A friendship album is a blank book usually given to young women who would loan it out to friends and family with the invitation that they write or draw something in it.

Entries were often personal, sometimes philosophical about ideas on love, art, or country. They are notable for their visual beauty and literary sensibility. The penmanship showcased is exquisite, especially to today’s viewers living in a modern world of electronic texts.

Smith says only five friendship albums from the 19th century are known to exist; the Library Company has three of them.

“It shows the everyday life of middle-class African-Americans,” she said. “Friendship albums show what they talked about, what they were drawing, what they were thinking.”

The album Smith put on display for this exhibition was compiled between 1833 and 1856 by a prominent African-American activist named Amy Matilda Cassey, who hailed from a solidly middle-class family. She founded Philadelphia’s first co-ed literary society, the Gilbert Lyceum.

One of her album entries was written by Frederick Douglass. The abolitionist apologized for not having the elegance of mind appropriate for a friendship album.

“I never feel more entirely out of my sphere, than when presuming to write in an album,” wrote Douglass in 1850. “It is mine to grapple with huge wrongs with gigantic tyranny — to launch the fiery denunciations of outraged and indignant men at the hoary headed oppressor! — This my dear friend is my apology for not writing something becoming the pages of your precious Album.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.