High-stakes judicial seats decided with little information, dearth of voter engagement

Voters will decide local races for Municipal Court and Court of Common Pleas, as well as help fill two statewide spots on the Superior Court of Pennsylvania.

Philadelphia's Criminal Justice Center. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

We’ve all done it.

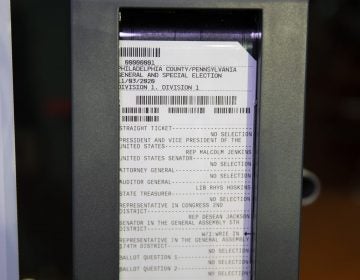

It’s Election Day, you’re in the voting booth, and you reach the section of the ballot with the list of candidates vying to become a city or state judge. Candidates you probably haven’t heard much — if anything — about until this moment.

So you pick a few names, perhaps based on party or ballot position, and walk out.

It’s understandable.

“If you come out of nowhere, and you’re not a big name that somebody recognizes, you just fall in line with the rest of them,” said longtime political consultant Michael “Ozzie” Myers.

That’s not to say judicial races aren’t important. The people voters choose preside over cases covering a range of high-stakes subjects, including violent crime, civil rights, and child custody.

During Tuesday’s general election, in addition to the mayor and City Council, Philadelphia voters will pick judges for Municipal Court and Court of Common Pleas, which handle local criminal and civil proceedings, as well as some traffic-related cases.

They’ll also help fill two statewide spots on the Superior Court of Pennsylvania, the appeals court that’s one step below the state’s highest court.

This common approach to voting for judges is largely a reflection of two things: state law and a dearth of voter engagement with these races.

Pennsylvania’s code of judicial conduct bars candidates from making “any statement that would reasonably be expected to affect the outcome or impair the fairness of a matter pending in any court.”

“Other than they’ll try to be fair,” said Myers.

That means out on the campaign trail, candidates are pretty much restricted to talking about their resume and record, which can be challenging to distill into a digestible stump speech to deliver to potential voters making their way into the supermarket or waiting for the subway.

Further complicating matters is that the people running for a judgeship are not necessarily natural-born political candidates.

“When you think about what it takes to be a great jurist, I wouldn’t necessarily have on the list loving to campaign and wanting to do a great deal of public addresses,” said Maida Milone, president of Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts.

How the Bar Association vets candidates

Every election season, the nonpartisan Philadelphia Bar Association tries to offset these obstacles by putting out a list of candidates they think are best for the job, based on their responses to a detailed questionnaire and an extensive in-person interview.

The association interviews people who had “professional dealings” with a candidate, examines candidates’ academic and professional backgrounds, and combs through their online presence, including social media accounts.

The organization also takes a long look at their trial experience, financial responsibility, and judicial temperament, among other qualifications.

The vetting process ends with a confidential vote, after which the association assigns one of three designations to the candidates they’re considering: highly recommended, recommended, and not recommended.

“The average person doesn’t know the candidates, so they’re looking to our recommendations [for help with making a decision],” said association chancellor Rochelle Fedullo.

It’s not a failsafe process. Candidates the bar association doesn’t recommend do get elected. But experts say the group’s ratings constitute the only comprehensive tool for voters looking to make informed decisions on Election Day.

Critics of judicial elections in Pennsylvania -— one of six states in the country where every judgeship is put to a partisan vote — say there’s another solution: appoint judges.

For years, Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts and other advocacy groups have pushed for a constitutional amendment that would make the state’s three appellate courts — Supreme, Superior, and Commonwealth — merit-based.

Instead of being elected, judges would be chosen by a nominating panel, made up of people with and without a legal background. The panel would send their picks to the governor, who would appoint them, subject to confirmation by the state senate.

The goal: create a more level-playing field for qualified candidates who don’t have access to big campaign bucks.

“Judicial races tend to be very low-information races and those candidates who are able to advertise themselves statewide are generally those who are able to raise a great deal of money,” said Milone.

Patrick Christmas, policy director for the non-partisan Committee of Seventy, a good government group, said some of that money — sometimes a whole lot of it — can come from PACs and super PACs looking to sway these races, which generally don’t have a lot of information that helps voters distinguish candidates from one another. Seventy has been an advocate for appointed judges.

“Every judge says that they are an experienced, credible attorney. Every judge says that they have ethics and that they have integrity,” said Christmas.

Tuesday’s election, however, is largely a foregone conclusion, aside from the Superior Court race, where four candidates are running for two slots.

They are: Democrats Amanda Green-Hawkins, and Daniel D. McCaffery; and Republicans Megan McCarthy King, and Christy Lee Peck.

In Philadelphia, there are seven open slots on the Court of Common Pleas and seven candidates running — Democrats Jennifer Schultz, James Crumlish, Josh Roberts, Anthony Kyriakakis, Carmella Jacquinto, Tiffany Palmer, and Crystal Powell.

There is one open Municipal Court seat and one candidate — Democrat David H. Conroy — running.

Incumbent jurists on the Superior Court, Commonwealth Court judges, Court of Common Pleas, and Municipal Court are also up for retention votes.

The election is Nov. 5.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.