Harnessing the immune system: Can plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients help the severely ill?

Antibodies that fought off coronavirus once might do so again. The treatment has been used for a century-plus, including in 1918’s influenza pandemic.

Listen 2:03

A donor laying on a transfusion chair while wearing a protective mask during blood donation in Bangkok. Thai Red Cross has requested blood plasma donations from patients recovering from COVID-19. (Photo by Amphol Thongmueangluang / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images)

Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

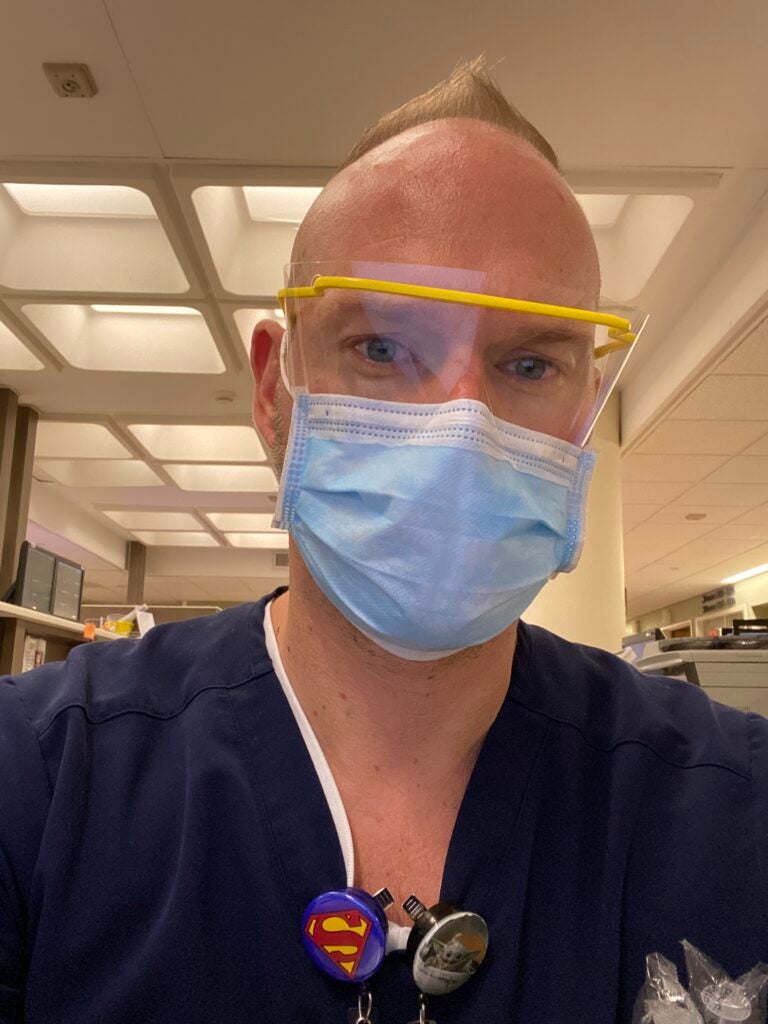

The night after he returned to Philadelphia in mid-March from a trip to Florida, Jim Gormley started to alternately feel warm and have chills. He received a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 about a week later — as a general surgery nurse at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, he was able to get priority testing.

Overall, his symptoms were mild: The warmth and chills lasted only one day; he also had a viral rash and lost his sense of taste and smell. After seven days without symptoms — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines at the time — Gormley headed back to work on March 31.

He felt lucky, and, as a health care worker, was looking for as many ways as possible to help during the pandemic. Gormley had heard about Penn Medicine’s call for blood plasma donations as part of a study researching convalescent plasma treatment for people with severe COVID-19 symptoms.

Plasma therapy involves extracting blood plasma from an individual who has recovered from an illness and transfusing it into a patient who is sick. Gormley saw Penn Medicine’s study as an opportunity to help those who had experienced similar, but more difficult health problems as a result of the coronavirus.

“I just feel like it’s my duty as a fellow human to join in the fight for this,” he said.

Used to treat viruses for more than a century, including during the 1918 influenza pandemic, the thinking behind plasma therapy is this: that antibodies in the plasma that fought off the virus in the previously infected patient may be strong and persistent enough to help the currently infected patient battling the sickness.

Hospitals and health systems across the country are working around the clock to collect convalescent plasma and get approval from the Food and Drug Administration to begin transfusing it into patients. There seemed to have been a few local breakthroughs last week.

In Pennsylvania, a Downingtown resident became the first person in the country to donate plasma through the Red Cross to two COVID-19 patients (including a family member). The person is now recovering. And at Virtua Voorhees Hospital in New Jersey, two COVID-19 patients who were in critical condition are recuperating after receiving plasma transfusions in early April. The 61-year-old man and 63-year-old woman are expected to return home from the hospital in May.

Convalescent plasma has not shown great success in randomized control trials, but in small pilot studies it has been effective in fighting many infectious diseases.

In mid-April, researchers in Wuhan published an article in the Journal of Medical Virology on results with six patients in the city that has become known as the epicenter of COVID-19 in China. According to the article abstract, the virus was eliminated in two of the patients after they received convalescent plasma therapy. In addition, an analysis of their blood determined an immediate increase in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody concentration in two other patients.

“This study indicates that convalescent plasma therapy is effective and specific for COVID‐19,” the abstract says. “This intervention has a special significance for eliminating SARS‐CoV‐2 and is believed to be a promising state‐of‐art therapy during COVID‐19 pandemic crisis.”

But there is still a lot to learn about plasma treatment because much of the research has been limited thus far — and because the pandemic may be the perfect storm of opportunity for discovering more about how the virus works.

Learning plasma’s effectiveness, on a large scale

Much more recently than 1918, convalescent plasma therapy was tried for treatment of H1N1, Ebola and the Zika virus. Emma Meagher, vice dean and chief clinical officer at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, said that in those outbreaks, the data on plasma’s effectiveness as a treatment is not very extensive. For example, there was a lack of potential donors researchers could draw from with Zika, which was mostly contained to South America, largely Brazil.

At Penn now, a two-part study is underway looking into the effectiveness of the treatment with COVID-19.

The first aspect of the study is a donor protocol, in which researchers are identifying people who previously had COVID-19 infections and are now at least 28 days’ symptom-free. Once someone is identified, the team invites that individual to Penn’s apheresis, or transfusion medicine suite so it can obtain one unit of plasma. The level of antibodies in that unit of plasma is then measured.

The second part of the study is the clinical trial protocol, in which patients currently in the hospital for COVID-19 treatment receive plasma. Meagher said that for this part researchers are interested in two patient populations: those who are critically ill in the intensive care unit and need mechanical ventilation, and patients who are less sick and not in the ICU but are still hospitalized.

This part of the study is based on enrolling 50 patients. Those who are critically ill will receive a unit of plasma on top of their regular COVID treatment. The results would be compared to a plasma study being conducted at the National Institutes of Health that has a placebo component.

Patients who are less severely ill will be part of a randomized placebo control trial. Half the patients will receive the regular standard of care and the other half will receive the plasma along with their normal treatment.

“The end points we are looking for in the clinical trial is to see if the antibody titers in the recipients — the patients who receive the infusion — rise and remain elevated,” said Meagher, who is helping to lead the study. “And we are also interested in seeing if those increases in antibodies correlate with an improved clinical outcome. Do they get off the ventilator earlier? Do they have a shorter hospital stay? Is their pulmonary function improved over a shorter period of time in comparison to a control group?”

By mid- to late May, Meagher said, researchers will have a good sense of the plasma treatment response and will be able to confidentially share their results so far with other centers.

The clinical trial component was recently greenlighted by the FDA through the request of an emergency investigational new drug application. She said her team planned to start treating patients this week.

One unique feature of the clinical trial also will include antibody testing.

Scott Hensley, a viral immunologist and microbiology professor at Penn, has helped develop a test to determine whether someone has ever been infected by the coronavirus. Hundreds of health care workers at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania have given blood so far, with the hope of determining if they have some level of immunity to the virus.

“We want to test patients serially so we can actually determine what the time course of antibody development is, which is really important to us in predicting the time course of recovery and allowing us to estimate how quickly people can return to health,” Meagher said. “We’re going for precision here. We want to try to see if the antibody levels themselves correlate with improved outcome.”

The aim is to roll the treatment out first at HUP and Penn Presbyterian, Meagher said, since they are two of the Penn health system’s most affected hospitals in the region right now.

Three hundred donors will be sought over the next four weeks — a high goal, she said, though finding eager and eligible donors is the least of their problems.

“We get people are in a spirit of giving right now and everyone wants to help in some way, and so we have lots of us fielding calls every day of patients who have recovered, friends of friends, college kids reaching out to say that they would like to do something,” Meagher said.

People who think they might be eligible can reach out through the Penn Medicine website.

In speaking with other health systems that have started the treatment, such as Mount Sinai and NYU Langone Medical Center, Meagher said, they are hearing anecdotally from physicians who have given plasma to COVID-19 patients that there have been no adverse effects and no toxicities so far.

“But they are very cautious to say it’s working, and I think that’s partly because it’s not being done in a sort of rigid experimental model where there isn’t a controlled experiment,” Meagher said.

What can we learn from antibodies?

Katie Bar is an infectious-disease professor at Penn and the lead investigator for this study. Her background is in HIV/AIDS research, in which she observed the ways the virus and human antibodies interact.

Bar said there are a lot of big differences between HIV and COVID-19, including how quickly people recover. Because of the quick turnaround, she said, there’s potential to boost the human immune responses to make it easier to treat.

“You mount antibodies through your natural infection, and if you give those antibodies to someone else they could neutralize, meaning bind and sort of kill or clear the virus,” Bar said. “There’s also this concept that these antibodies could help the rest of the immune system if you have a functioning antibody. It could help your cellular responses, your ability to identify infected cells and kill or clear those, your ability to sort of tamp down inappropriate immune response.”

Bar said they may also be able to figure out when is the most effective time in someone’s illness to receive convalescent plasma.

Despite the lack of strong data so far on convalescent plasma’s efficacy, Bar said researchers in the infectious-disease and transfusion medicine communities hold out hope.

“The point is we don’t have any proven therapies [for COVID-19 yet],” Bar said. “We have some promising antivirals, they have relatively limited availability right now, and those trials are still ongoing, so we are kind of living in this world where we don’t have any other therapy that is proven.

“For this, and other infections where there is no good treatment, this sort of harnessing of the best that the immune system has to offer is a really good place to start.”

Gormley, the HUP nurse who donated plasma after his COVID recovery, was hesitant to donate at first.

“I am a gay man, and I know even though it’s 2020, there’s still a ban on gay men donating blood,” he said. “You always come into something like this … in the back of my mind, feeling like you’re still considered second class. I was like, if I can help someone who’s dying, like we can deal with all of that other stuff later.”

Under previous FDA guidance, the Red Cross only accepted donations from gay men who had abstained from sex for 12 months. With the pandemic, the FDA has revised the guidance to three months.

Gormley was also inspired to donate after a mutual friend’s mother was severely sick with the coronavirus and was on a ventilator. He was asked to donate his plasma to her, but it never worked out logistically.

“It’s destroying people’s families,” he said. “I was just thinking to myself, if it were my mother, in that situation … I’d be in hysterics, but I’d wish somebody would donate my plasma and do anything they could to help her get out of it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)