Grounds For Sculpture is exhibiting a 50-year retrospective of Michael Graves’ work

For Michael Graves, it all begins with lines on paper.

His otherwise serious demeanor becomes playful when his hand wields a drawing implement. And his pen can’t keep still during meetings.

Despite running busy design practices in New York and Princeton (Michael Graves & Associates and Michael Graves Design Group), he travels to China, Nebraska, Florida and Rome, parenting duties, and enduring paralysis from the waist down, the 80-year-old Princeton resident draws and paints nearly every day.

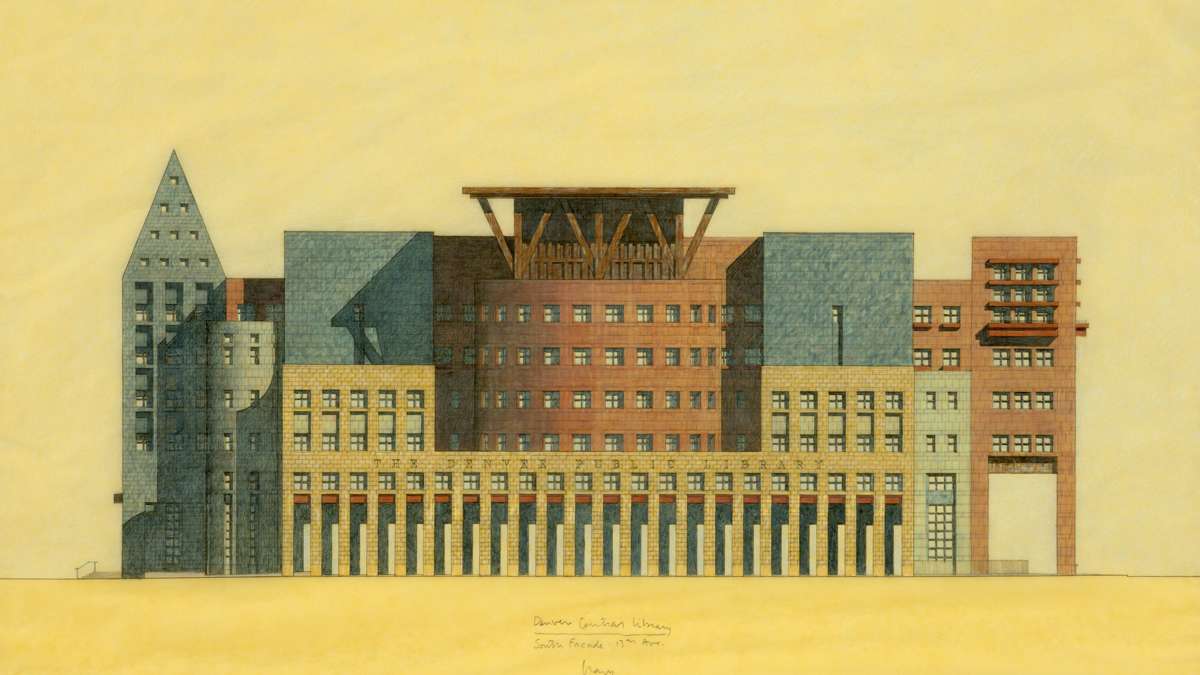

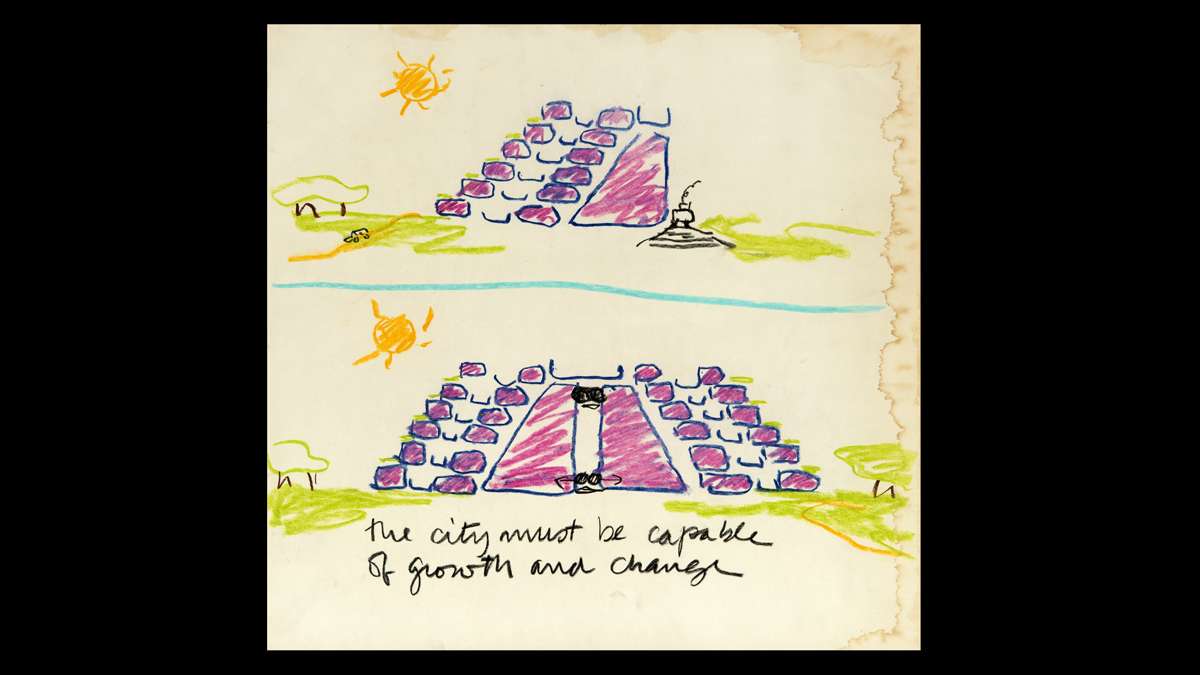

Grounds For Sculpture is exhibiting a 50-year retrospective of Graves’ architectural models, photographs of built projects, furniture, product designs, paintings, sculpture, work in progress and, yes, drawings, in Past as Prologue, on view through April 5, 2015.

Beginning in the mid 1960s, Graves emerged as a visionary. With architect Peter Eisenman, then also unknown, he designed the Linear City Project, a mile wide and 20-mile- long concept consisting of parallel strips for industry and homes, shops and services, with highways running below a natural landscape. It was envisioned to alleviate traffic jams.

At Grounds For Sculpture, a photograph of the El Gouna Golf Hotel in Red Sea, Egypt, shows what at first looks like a Michael Graves design fitting perfectly with the surrounding architecture. In fact, the surrounding architecture IS the El Gouna, all designed by Graves. The El Gouna is the only thing on the landscape.

“It was built in the desert,” Graves says of the luxury golf resort. “The only way to get there is to fly. Once you’re there you don’t need to go anywhere. You go to the beach, ride horses, play golf, eat in the dining room and relax.” Even the bricks for the hotel were made from desert sand.

Closer to home, the U.S. 1 Corridor contains a number of Graves’ buildings, including the Arts Council of Princeton’s Paul Robeson Center for the Arts, the Miele headquarters, the MarketFair interior, and several homes, including his own Mediterranean villa made from a former warehouse.

Michael Graves Design Group has planned more than 2,000 products, from lighting, hardware and bath projects to the Alessi whistling bird teakettle, for which he became a household name. “The link throughout my work is humanism, whether I’m working in product design or architecture,” says Graves. “It’s always about the human being.”

Winner of the 2001 Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects and 2012 Richard H. Driehaus Award, Graves is the first architect inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame, and the first recipient of the Michael Graves Lifetime Achievement Award from the AIA-NJ.

Earlier in his career, Graves painted murals in private homes and in lobbies, conference rooms, and doctors’ offices. His architecture, with its signature use of color, has always been described as painterly. Drawing is central to his way of thinking about architecture.

During his 39-year tenure as Robert Schirmer Professor of Architecture at Princeton University, Graves encouraged students to see drawing as an essential part of conceptualizing building design. “Architecture cannot divorce itself from drawing, no matter how impressive the technology gets,” Graves wrote in an Op-Ed piece in The New York Times two years ago. “Drawings are not just end products: they are part of the thought process of architectural design.”

When living in Rome, he developed a compulsive desire to record what he saw throughout the cities and countryside, experimenting with various drawing methods to best express the subject matter.

Italy in still in his psyche, and those early drawings and recollections inform the paintings of Tuscan landscapes he works on in his home studio.

When Graves was growing up in Indianapolis, he would draw all the time. To spare him the life of a starving artist, his mother suggested he pursue a career in either engineering or architecture. First, she told him what an engineer does.

“I’ll be an architect,” was his reply.

“But I haven’t yet told you what an architect does,” his mother said.

“It doesn’t matter,” he told her. “I know I don’t want to be an engineer.” His high school ran out of courses for him and had to create a few more so he could continue to draw.

Most architects have a low ratio of buildings built to buildings designed, but Graves estimates that roughly half his designs have been actualized. And although one burned to the ground, at least none has been torn down, like the American Folk Art Museum building, the highly regarded design by starchitects Billie Tsien and Tod Williams, slated to be razed by its neighbor and new owner, the Museum of Modern Art.

“Don’t get me started,” says Graves.

His own Portland Building, built in 1983 and considered one of Oregon’s most important buildings, is facing a $95 million renovation, and some are calling for its demolition.

At the time it was built, it was seen as a significant work of postmodernism. It won an AIA award in 1983 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

Because of his knowledge of being confined to a wheelchair, Graves has designed a line of products for the patient room designed from the patient’s perspective. The University Medical Center at Princeton in Plainsboro incorporates his designs. He has been designing wheelchairs since 2013.

The octogenarian has no plans to retire. “I don’t run as fast as I used to,” he jokes. With 12 honorary doctorates, 10 major publications, and awards too numerous to list, Graves adds, “I can’t afford to retire. Architects don’t make that much money.”

________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.