‘Frustrated and disappointed’: Child care providers in Pennsylvania call on governor for help

Child care providers and advocates are urging Gov. Wolf and other policymakers in Harrisburg to quickly allocate money in a way that avoids closures of child care centers.

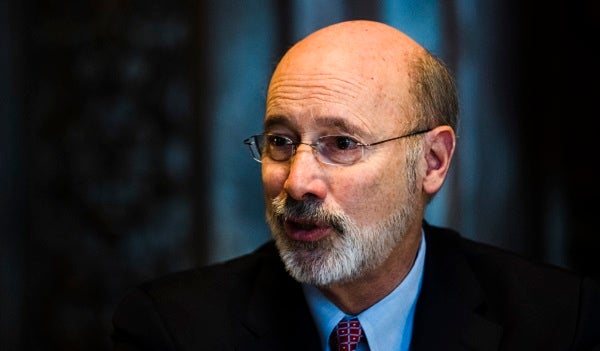

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at his office in Harrisburg, Pa. (Matt Rourke/AP Photo)

This article originally appeared on Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

—

Pennsylvania child care providers, advocates, and key legislators renewed pleas to Gov. Tom Wolf’s administration last week to release $302 million in federal aid — but change how it is distributed to child care centers.

Every week, child care centers are being forced to lay off workers or face closure due to soaring costs and a state subsidy system that abruptly changed in September, decimating their finances.

Despite months of advocacy on the issue, nothing has changed.

“I know Gov. Wolf cares” about saving the child care sector, on which so much of the state’s economy depends, said Nancy Thompson, executive director of Jolly Toddlers in Bucks County, a sentiment echoed by others involved in a Zoom press conference last week. “That is why I am so frustrated and disappointed.”

Public Citizens for Children and Youth organized the press conference, which featured legislators from the Women’s Health Caucus. They and the providers said the collapse of the industry disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color, many of whom either work in child care or rely on it. Widespread closure of child care centers would hurt working families across the state, they said.

Providers and advocates began drawing attention to the issue last summer, when the state said it would change its subsidy reimbursement policy in September. The change based subsidies on currently enrolled students, rather than pre-pandemic enrollment numbers, leading to a sharp drop in reimbursements at the same time that providers were spending more on health measures to mitigate the spread of the virus.

Of the $900 billion federal relief package already passed by Congress in December, $10 billion was earmarked for the child care industry. About $302 million of that is expected to go to Pennsylvania through the Child Care Development Block Grant, which supports state-subsidized child care for low-income families.

But the state Department of Human Services said it still does not have all the official details from Washington.

“The Department of Human Services is reviewing the recently signed Consolidated Appropriations Act and guidance on allowable uses and determining its impact on Pennsylvania and the programs and services we administer,” wrote Erin James, press secretary for the DHS. “We are grateful for the additional support and will continue to work with the incoming Biden administration and Congress to ensure Pennsylvania and other states have the funding needed to navigate the pandemic and economic uncertainty.”

They have until Feb. 25 to submit their plan to the federal government, but have not outlined how the funding might be distributed or what the priorities might be.

Providers and advocates are urging policymakers to quickly allocate the money in a way that avoids further closures of child care centers. They would like to see the subsidy policy changed to account for enrollment declines since the start of the pandemic.

As of late December, about 480 child care centers have permanently closed, according to a letter sent to Tracey Campanini, deputy secretary of the Office of Child Development and Early Learning, or OCDEL, from a coalition of 10 child care advocacy organizations, which make up Start Strong PA. Some providers believe that number is higher because smaller centers that accept only private pay can be harder to track than those that accept public funding.

In the letter, providers and advocates proposed a number of recommendations for how federal money could be used to help both working families and child care centers. The letter was in response to a call for policy recommendations from OCDEL.

The first priority was consistent with the message of Thursday’s press conference in pressing for reestablishing subsidized funding based on pre-pandemic enrollment. Child care centers often rely on both government subsidies and direct payments from more affluent families — but a spike in unemployment during the pandemic also has made private payers scarce.

Some providers across the state and the country have taken out personal loans or have taken on other forms of debt in order to cover costs. Others have had to layoff staff or cut workers’ pay.

“In regular times, our system is based on enrollment, and I can pretty much get behind that,” said Leslie Spina, director of Kinder Academy. “You shouldn’t get paid if children aren’t there. But this is not the normal time.”

Spina has seen a 50% drop in enrollment since March, when the pandemic forced schools and centers to close. Since then, she has had to close one of her five Philadelphia locations, shift a second to a virtual program, and put on hold construction on a sixth center that was near completion. Spina estimates that her costs have doubled since the pandemic started.

Providers and advocates are confident that enrollment will increase as vaccination rates go up and things start to return to normal. Before the pandemic, childcare centers across the state consistently had waiting lists.

With enrollment from every possible direction decreasing, the fixed costs for providers have increased during COVID-19 as child care centers partition staff into strict “pods” that limit staffing flexibility, escalate cleaning protocols, purchase individualized supplies, and incur other pandemic-related expenses.

Advocates and providers also have asked the state to provide financial relief directly to child care staff, who are not represented by unions and don’t receive hazard pay.

The child care industry has said nationally it needs about $50 billion to survive the pandemic. They would reach that number with the $10 billion approved by Congress in December and the $40 billion included in President Joe Biden’s proposed $1.9 trillion stimulus package.

Even before the pandemic, gaps in affordable child care made it difficult for some parents to work in Pennsylvania. The Center for a Strong America estimates the cost of that to be as high as $2.5 billion.

“Employers were struggling before to find workers because of issues with access and affordability of child care,” said Steve Doster, the Pennsylvania State Director of Council for Strong America and a signatory of the letter.

Advocates believe there could be a need for more child care subsidies, even after the pandemic.

The letter said: “Families, who most likely exhausted savings to make ends meet, will return to the labor force with significantly fewer financial resources resulting in a need for subsidized child care.”

Advocates also fear that federal funding might make the child care industry an easy target for state budget cuts, especially as state revenue has decreased since the pandemic.

“There will be an in-depth desire on the part of the House leadership and the Senate leadership to say, $300 million came in from the feds, we can reduce state funding by that amount,” said Donna Cooper, Executive Director of PCCY.

“PA Republicans and Democrats need to say this money is not going to supplant state funds,” said Cooper, otherwise “you’re begging for the money you used to have to be replaced.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.