At the heart of it all is a heart: Franklin Institute built a state-of-the-art exhibition around an old-fashioned favorite

The “Body Odyssey” exhibit makes visitors’ own bodies part of the show.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The biggest heart in the City of Brotherly Love beats anew.

The Franklin Institute’s giant walk-through heart has been closed as the science museum developed a new, permanent exhibition around it. “Body Odyssey” opens this weekend with state-of-the-art museum technology showcasing the human body, from gut microbiomes to bionic prosthetics.

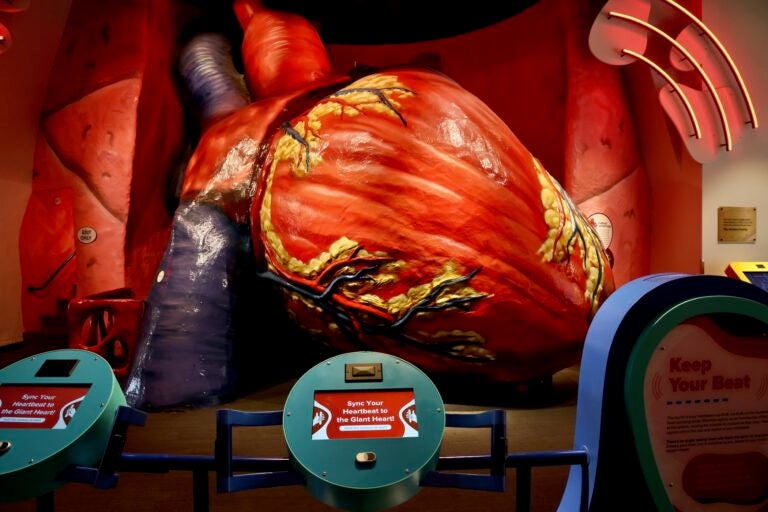

As it has been for the past 70 years, the heart is the centerpiece. In 1954, it opened as an exhibit constructed from four tons of paper mache and resin that demonstrate how blood moves through ventricles and lungs. At the time the organ, built like an educational treehouse, was temporary but has since become one of the most beloved exhibits for generations.

“The heart is the most iconic thing about the Franklin Institute,” said Abby Bysshe, chief experience and strategy officer. “It’s probably one of the most iconic experiences in the museum industry. So we don’t touch that. That is something that we try and emulate.”

Built for children — with tight tunnels and stairs only small bodies can comfortably squeeze through — the old fiberglass resin still gives it a slightly funky smell, but it has been upgraded with a new feature that’s truly heartwarming: A kiosk with heartbeat sensors can take the pulse of a visitor and transfer it to the big heart, making it almost like walking through your own organ.

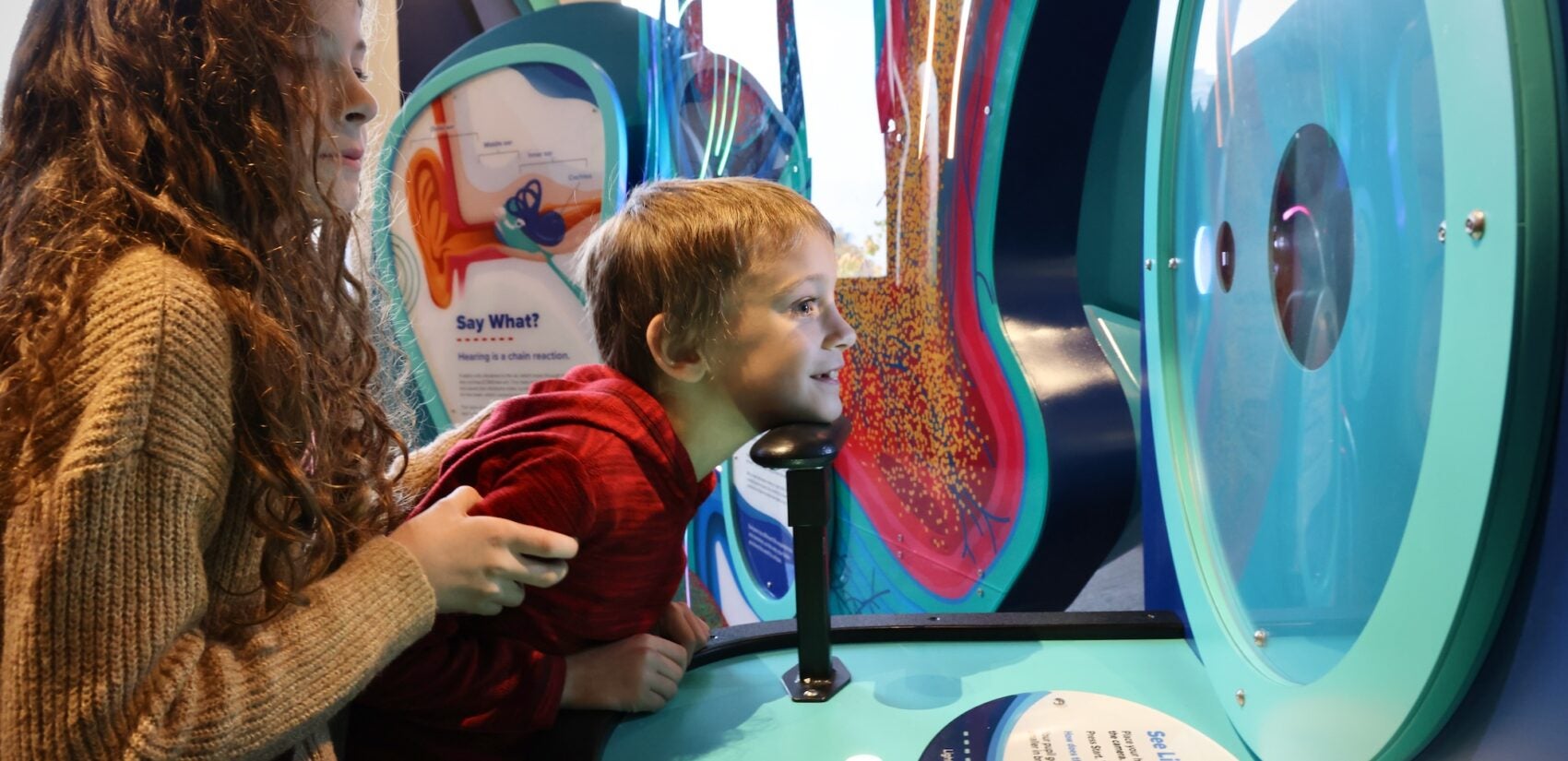

The rest of “Body Odyssey” doubles the footprint of what the heart exhibition used to be to about 8,500 square feet. Many of the exhibits have sensors that take readings from various parts of the bodies of visitors, like pupils, veins and muscle systems moving through space in real time. It then uses that information to reveal insights into how the body functions.

Your body, in a sense, becomes the display.

“The great thing about an exhibit on the human body is you’re bringing one to the experience,” Bysshe said. “We want to make sure that we’re using that as much as we can when we’re creating these experiences, so they feel personal to you.”

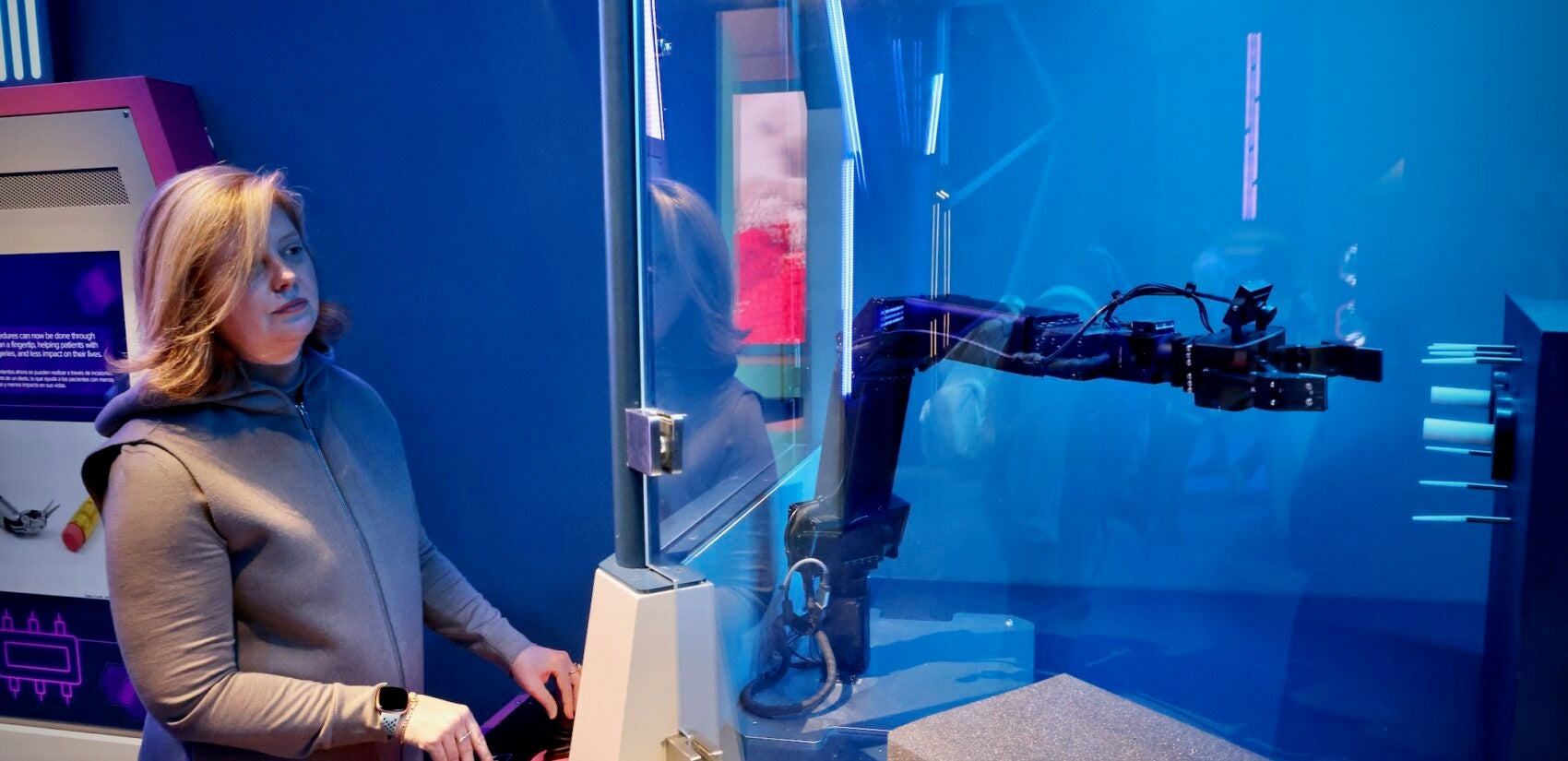

“Body Odyssey” also shows what it takes to be more human than human. The exhibition includes a room of technological innovations in sports training, robotic surgery and mechanical prosthetics. Medical products get their time to shine, too, like an electrocorticography grid or a thin film of sensors that is fitted directly onto the surface of the brain to track impulses.

On another floor of the building, the Franklin Institute is also reopening its Baldwin 60000 train, a 1926 experimental locomotive donated in 1933 by an ancestor of the Hamilton philanthropic family, Samuel M. Vauclain. Weighing 350 tons, it rests on a platform of architectural trusses and has never moved an inch in more than 90 years. The new Hamilton Collections Gallery was built around it.

The Collections Gallery features two-story-high glass storage cases that are two stories high that extend from the research area below up into the locomotive room. The cases hold artifacts from the institute’s collection of about 40,000 objects, mostly historic science instruments that visitors can peruse.

“It’s great to have collections, but if people can’t see them they sit behind closed doors,” said Franklin Institute President and CEO Larry Dubinski. “We created this open visual storage so people could look into them.”

The cases will be changed periodically to showcase different themes of the collection. The opening exhibition features 200 objects representing 200 years of science, including Benjamin Franklin’s static electricity generator, a working miniature model of the Strasbourg astronomical clock that retailer John Wanamaker displayed in his department store on Market Street, and a Black astronaut Barbie doll from the 1990s still in its box.

“My hope is that children, including my own Lane, Colby and Marley, will walk into this gallery not only thrilled by the train, but also feel the spark of curiosity and inspiration,” said Samuel M.V. Hamilton of the Hamilton Family Charitable Trust, which funded the new gallery.

The “Body Odyssey” exhibit and Hamilton Collections Gallery are the latest phases of an ongoing, building-wide renovation to upgrade and reimagine the Franklin Institute. Next up will be a new exhibition about Earth science, expected to open in 2026.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.