Five decades later, Penn hosts second-ever teach-in

Morning Edition host Jennifer Lynn speaks with Penn's Ira Harkavy about the university's second-ever teach-in.

Listen 5:46

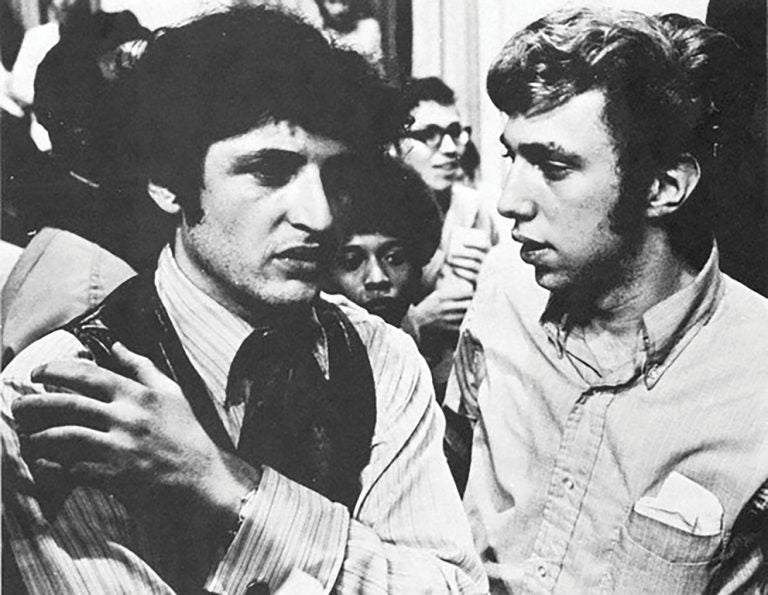

Sociology professor Phillip Pochoda (left) and student leader Ira Harkavy during the 1969 Penn sit-in in College Hall. (Courtesy of “Collections of the University Archives and Records Center")

The teach-in movement monopolized the 1960s. College and university campuses held forums, often in reaction to U.S. engagement in the Vietnam War. They included lectures, movies, and debates — some taking shape over the course of days. In 1969, the University of Pennsylvania hosted its own teach-in. Nearly 50 years later, the university is hosting another one, covering race, vaccine denial, immigration, and much more.

Morning Edition host Jennifer Lynn spoke with Ira Harkavy, who was a junior at the College of Arts and Sciences back in 1969. He’s now the founding director of Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnership and has a role in Penn’s second-ever teach-in, which begins this week.

—

What were students going through in 1969, in light of the Vietnam War and on the heels of the civil rights movement?

That was certainly a tumultuous period, and you captured the two issues that people focused on: issues of civil rights and issues of war in Vietnam and America’s engagement. There was deep opposition that existed toward the war in Vietnam, and there was deep concern about America’s treatment of African-Americans and how we could achieve the equality that this society promised for all its people. And students were focusing not only on their own futures but very much about how, in fact, steps could be taken to end the war in Vietnam and to significantly improve the treatment of African-Americans in American society.

And this was cerebral, political, visceral?

Visceral, cerebral, political. Cerebral connected to action. This wasn’t cerebral in the sense of debating societies. This was cerebral in the sense of the need to think about these things because, first of all, we were thinking about them—but the idea, also, that we had to do something. That there was a sense of urgency, not just here but throughout the world.

These things (teach-ins) were long, sometimes running overnight for several days with lectures and movies and debates, musical events. Fifty years ago, Penn referred to this as a day of conscience. What was that event like?

So I think that’s very important that this was a day of conscience, because it came on the heels of a sit in that focused on the question of the use of knowledge and the misuse of science. There were issues related to the functioning of the University City Science Center where, in fact, research was done as I recall on defoliants, possibly on napalm.

And this was an institution connected to Penn and other higher educational institutions; Penn was the largest shareholder. There was deep concern about that. And also the sit in focused on Penn’s treatment of the West Philadelphia community and, in fact, expansion of Penn North and the removal of people who lived in what was called Unit 3 or the Black Bottom. The teach-in, which occurred two weeks later, that focus on a day of conscience was a critique of what Penn was doing in other institutions of higher education. So there’s a day of conscience as it relates to issues of how we treat our neighbors when the teach-in happened. I don’t remember personally running from session to session, but I do remember there was a feeling that this is what education is about. There was a feeling that this is intellectually exciting and a way to really learn.

This time around the topics range from race, to fire arms, to what’s called vaccine denial. There are going to be round tables, town halls, and a TED style talk, and lectures. How are all of these events designed to promote dialogue around difficult subjects?

The way this gets done, I believe, to get real conversation is pose the problem. How do we solve the problem is the most effective way of engaging individuals. It really comes to great educational philosopher John Dewey. Thinking begins where there’s a problem to be solved. So it isn’t just ‘let’s discuss this.’ It’s discuss it, analyze it ,and discuss what should and could be done and how do we do it to make a difference. That’s the best way, and that’s why the teach-in the ’60s was so live. It was about real problems in action and much of what’s being done in this coming teach-in is exactly oriented that way.

Solutions. Will there be solutions?

I think ideas will come out that could be part of solutions. You don’t expect that a single solution is going to come from any teach-in, but it is starting the process or is accelerating the process. We have to learn from implementation, from engagement. The idea that this is not just one activity but part of an ongoing conversation.

We’re speaking just after the National School Walkout where many high school kids, middle school kids, even elementary age kids walked out in defiance, in protest, in hoping to make a change. You made a career out of civic dialogue. What are words that you can put in the ears of some of our very young listeners who are now thinking, ‘Oh, this is a kernel for me to start my new way of doing things?’

The only thing I can impart with them is how the most important single issue it seems to me is the idea that what you do matters, and the only advice I would have for the young people throughout the country, who are marching and demonstrating, is keep it up and keep it peaceful and keep it focused—and do this work and keep doing it the way you are doing it with dignity and standing for moral things.

Disclosure: WHYY is a sponsor and partner of Penn’s 2018 teach-in.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.