First Year, First Generation: The final verse

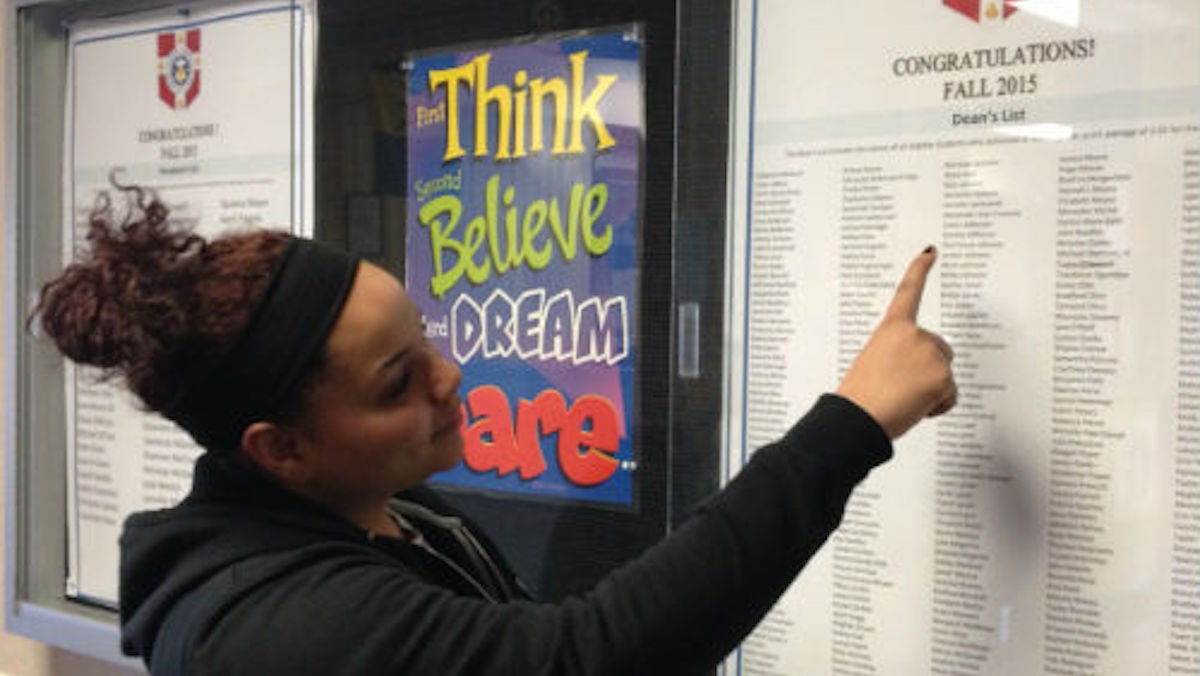

First-generation student Cierra Jefferson (photo courtesy of Jefferson)

This is the final story in our First Year, First Generation series. For an introduction, click here. You can listen to Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6 by clicking on the links.

We started this project hoping to gain a glimpse into the world of first-generation college students. We produced stories. We cataloged dozens and dozens of audio diary entries submitted by the students. And after all that, the most complete picture of what it means to be first generation came out of the very last question we asked.

Was there a moment in this whole experience where you really felt like a first-generation college student?

In every final interview, I asked the students some version of that question. Together their answers painted a stunningly complete portrait of life as a first-generation college student: humor, alienation, frustration, triumph. Also, by pure coincidence, each student’s quintessential first-generation experience came at a different point in the school year: summer, fall, winter, and spring.

Josee Lazarre

We start with Josee Lazarre, whose response took her back to last summer — before college even began.

A student at Delaware Technical and Community College in Southern Delaware, Lazarre’s first-generation moment came when she got her student ID picture taken at student orientation. In it, she’s wearing a wide grin — similar to the one that spreads across her face as she reminisces about picture day.

“I was so happy that day. I was like, ohmigosh, I’m really getting into college,” Lazarre said. “Like that was the surreal moment of the whole process.”

Lazarre immigrated from Haiti when she was 12. She knew no English. Six years later, she was attending an orientation, ready to enroll full time at an American college. This thing her parents could have only dreamed about, she was doing it.

“That moment, like, you know, asking questions, visiting campus, like how the whole thing was gonna be,” she said, grasping for the words. “It doesn’t seem like a big deal, but to me it was. It was a big deal to me.”

Lazarre finished the year with a grade-point average just a shade under 3.0. She decided toward the end of the year she wouldn’t pursue a bachelor’s degree after completing her two years at community college. Instead, she plans to enroll in a special nursing school and go quickly thereafter into the workforce.

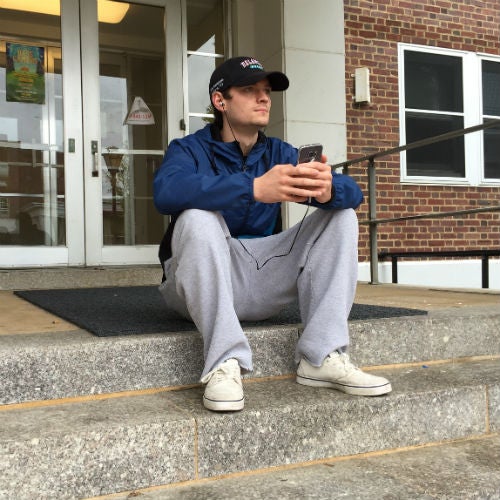

Sean Ryan

As summer turned to fall, I predictably heard more and more from the students about school work. The word “stressed” popped up … a lot. Sean Ryan, a student at the University of Delaware, struggled early in his classes. He didn’t know, for instance, what the word “syllabus” meant, and he missed a slew of reading assignments. Plus, the work was harder and lonelier than he expected.

His first-generation experience came after he got a “D” on his first math test, a test given in a remedial course to which he’d already reluctantly been relegated.

“I didn’t know who to talk to about it,” said Ryan. “Like, I couldn’t call my mom and be like I did all this for nothin’. Or call my dad. Neither of them went to college.”

Ryan felt isolated, and not just when it came to academics. He suspected his parents could relate to a lot of the stuff he was going through in college: roommate trouble, homesickness.

“But just because I’m in college I feel like I can’t ask them about it,” said Ryan.

Throughout his first year, Ryan toggled between a desire to leave school and a determination to finish. He told me he’d never really expected to be in college. When things got tough — as they did regularly — he often defaulted to this notion that he should drop out.

He stayed because he didn’t want his first-year struggles to go to waste.

“It’s just like … I don’t know if you saved up money to buy a pair of shoes you really wanted,” said Ryan. “You’re gonna wear those shoes.”

He plans to live on campus again next semester and wants to be a Spanish teacher when he graduates.

Cierra Jefferson

For Wesley College student Cierra Jefferson, her quintessential first-generation moment came over Christmas dinner. Specifically, it was the moment she walked into her aunt’s house in rural Delaware.

“And we were all in the living room and you know people were coming in and just arriving and all my cousins were like sittin’ on the couch and it kinda brought me back to a time when we were little,” she said.

And almost immediately Jefferson’s younger cousins started to ask her about college. They asked her if she likes school. They asked her about her roommates. It’s all the typical things you ask a first-year student when she finishes that first semester, but it gave Jefferson this epiphany.

“It kinda hit me … knowing that I was the one in college,” Jefferson said. “They look up to me.”

Jefferson proved a stellar student at Wesley, finishing on the dean’s list. She was accepted into the school’s nursing track and has maintained the grades so far to remain in the program. By her own admission, she never totally adjusted to college life. She worked two jobs throughout the semester and spent most of her free time at home.

Jada Smack

Jada Smack’s transition from a small town in rural Delaware to prestigious Swarthmore College also had its bumps.

“Any situation where I’m reminded where I come from makes me feel like a first-generation student because, like, people literally say no one cares about where you come from,” said Smack. “So, yeah, that kinda sucks.”

Often the reminders were subtle. Smack recalled her classmates’ incredulous reactions when she told them she was eating pesto for the first time. But the experience that really drove it home came at the end of the year. A friend asked her to help set up for a graduation garden party at nearby Bryn Mawr College. As she prepared everything, she started to look around and her jaw dropped

“There was silver plate-ware,” said Smack, trying to contain a laughter drenched in disbelief. “Like real ones, though. They had fruit dishes. And like cheese dishes. And like cheese I’ve never heard of before — with all these nasty spreads and stuff.”

Surveying the scene, Smack felt an odd mix of emotions. She was in awe. She was uncomfortable. She was amused.

“It was so bougie,” she said. “It was the most bougie thing I’ve see in my entire life.”

And then she was hit with a really powerful version of a thought she had experienced in small doses ever since she began at Swarthmore.

“They’re gonna look at me and be like, ‘Oh my God, that person doesn’t belong here,’” said Smack.

Despite those nagging doubts, she adapted well to campus life. She joined clubs, managed the basketball team, and developed a network of close friends. Early in the year, Smack felt pulled toward her home town, making the 2-hour trek home more often than even she’d expected.

But as her friend circle grew and her campus activities multiplied, she grew more comfortable at Swarthmore. When the school year ended, she decided to spend the summer on campus instead of returning to her hometown.

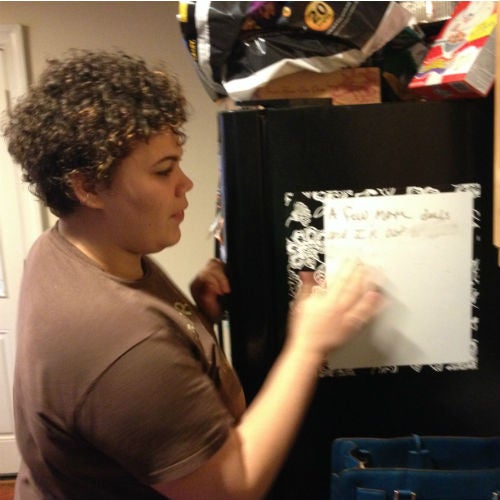

Jacki White

One of the five students didn’t answer our final question.

Jacki White’s first year at the University of Delaware was a revolving door of crises.

A brilliant student when engaged, White found it nearly impossible to concentrate in core classes where she cared little about the content. That lack of concentration slipped into depression. The depression gathered force throughout the semester, to the point where she found it difficult to even leave her room — much less complete assignments.

“The closer I got to finals, the more I disassociated, ignored, shut out, and shut down,” said White. “That’s something scary, when you can’t move yourself.”

White likened the early stages of her depression to the sensation of wearing stockings.

“When you have stockings on, it’s like a thin layer. When something touches you it’s there, but it’s not,” White said. “That layer just felt thicker and thicker until you start to feel more and more numb.”

It was difficult to watch a person of such clear intelligence — capable of poetic, spontaneous turns of phrase like the ones above — break down. But break down White did.

The end of the first semester provided some respite, and would have provided more if White didn’t confront another obstacle. Midway through winter break, she was told she owed the university nearly $8,000 — an amount that sent her into panic. The bill was actually a mistake, but it took White almost a month to uncover the error and decide she would indeed attend school for a second semester.

When she returned to UD, White enrolled only in art classes and seemed to re-engage. White is an art major, and she was able to find the motivation necessary to at least get by. Toward the end of the semester, she told me she’d had a brutal fight with her mom and wouldn’t be returning home over the summer. She planned instead to live with extended family.

I haven’t spoken with White since.

Her phone broke and she communicates only sporadically over email. I’ve made several attempts to arrange meetups, but all have been derailed.

According to the university, she is still enrolled as a student. I was never able to ask her our final question.

White’s struggles may have been the most acute, but all five students had moments of doubt. Each also had moments of triumph — a good grade, a new relationship — that seemed to validate their push toward a degree.

No one dropped out—despite a few close calls. All five began the year as pioneers. The best news is, they still are.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.