‘Not dead but … not OK’: As fentanyl kills fewer people, survivors need help

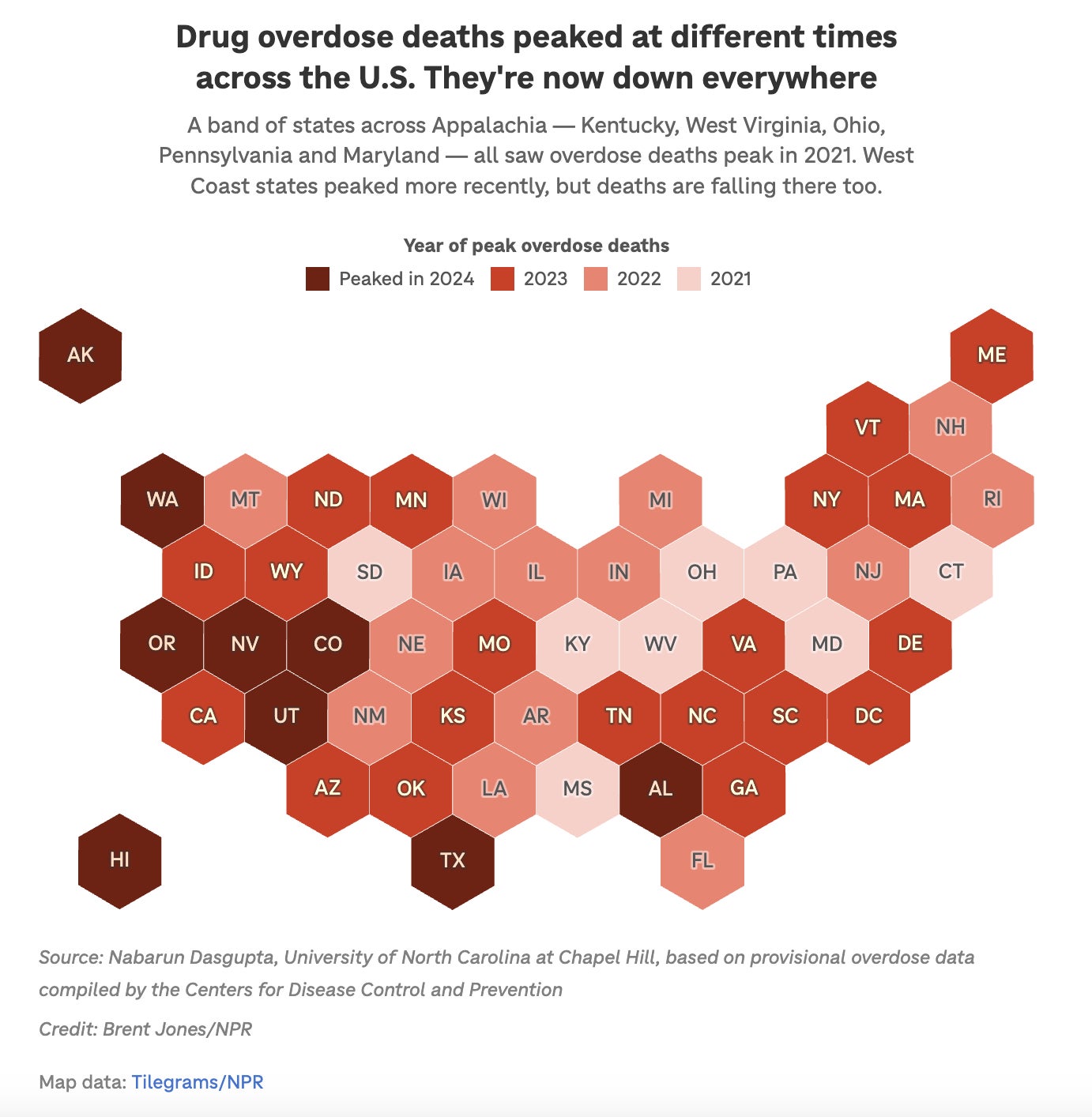

Pennsylvania is seeing roughly 2,000 fewer drug deaths a year. Nationwide, the number of annual deaths from drug overdoses has dropped by more than 30,000 people a year.

Larry Anderson (center), director of prevention services at Prevention Point, a harm reduction nonprofit, collects donations in the Kensington neighborhood before the group's walk-in clinic opens for the day. (Rachel Wisniewski for NPR)

This story originally appeared on NPR’s “All Things Considered.”

On a blustery winter morning, Keli McLoyd set off on foot across Kensington. This area of Philadelphia is one of the most drug-scarred neighborhoods in the U.S. In the first block, she knelt next to a man curled on the sidewalk in the throes of fentanyl, xylazine or some other powerful street drug.

“Sir, are you alright? You OK?” asked McLoyd, who leads Philadelphia’s city-run overdose response unit. The man stirred and took a breath. “OK, I can see he’s moving, he’s good.”

In Kensington, good means still alive. By the standards of the deadly U.S. fentanyl crisis, that’s a victory.

It’s also part of a larger, hopeful trend. Pennsylvania alone is seeing roughly 2,000 fewer drug deaths a year.

Nationwide, the number of annual deaths from drug overdoses has dropped by more than 30,000 people a year.

That’s according to the latest provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, comparing drug deaths in a 12-month period at the peak in June 2023 to the latest available records from October 2024.

Officials with the CDC describe the improvement as “unprecedented,” but public health experts say the rapidly growing number of people in the U.S. surviving addiction to fentanyl and other drugs still face severe and complicated health problems.

“He’s not dead, but he’s not OK,” McLoyd said, as she bent over another man, huddled against a building unresponsive.

Many people in Kensington remain severely addicted to a growing array of toxic street drugs. Physicians, harm reduction workers and city officials say skin wounds, bacterial infections and cardiovascular disease linked to drug use are common.

“It’s absolutely heartbreaking to see people live in these conditions,” she said.

Indeed, some researchers and government officials believe the fentanyl overdose crisis has now entered a new phase, where deaths will continue declining while large numbers of people face what amounts to severe chronic illness, often compounded by homelessness, poverty, criminal records and stigma.

“Initially it’s been kind of this panic mode of preventing deaths,” said Nabarun Dasgupta, who studies addiction data and policy at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. His team was one of the first to detect the national drop in fatal overdoses.

His latest study found drug deaths have now declined in all 50 states and the trend appears to be long-term and sustainable. “Now that we have found some effective ways to keep people alive, it’s really important to reach out to them and try to help them improve their whole lives,” Dasgupta said.

Building a safety net for an evolving fentanyl crisis

That’s a tall order. Some help is on the way as states continue to disburse roughly $50 billion in settlement money paid out by corporations that helped fuel the first wave of the opioid crisis by aggressively making and marketing highly addictive pain pills. Pennsylvania has already received roughly $209.9 million.

But at a time when the need for services is expected to rise, there’s new uncertainty about the Trump administration’s support for government agencies, nonprofit groups and hospitals that provide addiction treatment.

According to members of Congress, the White House has already slashed 10% of the workforce from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a key agency within the Department of Health and Human Services focused on the addiction crisis.

In a letter sent this month to HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., more than 50 Democratic lawmakers described the cuts as “reckless.”

The letter argues federal workers have been “instrumental in supporting this decline in [drug overdose] deaths” and warns job cuts will cripple crucial treatment services, including mobile units that treat fentanyl addiction.

Some Republicans are also proposing federal budget cuts that could affect Medicaid, the largest funder of drug treatment health care in the U.S.

“There are never enough resources,” said Cari Feiler Bender, spokesperson for a harm reduction organization in Philadelphia called Prevention Point. “Last year, we worked with 23,000 people, but our funds have been cut in many areas.”

According to Feiler Bender, Prevention Point contributed to the drop in deaths in Philadelphia by providing free health care and by distributing more than 100,000 free doses of naloxone, also known as Narcan, to people who use drugs last year. The medication reverses most opioid overdoses, including from fentanyl.

Working from a converted church in the heart of Kensington, the organization is now trying to help people move beyond subsistence and severe addiction.

“You can come in any time, you don’t need an appointment,” Feiler Bender said during a tour of Prevention Point’s free clinic.

“Today you need wound care? Today you need your HIV injection? Or you can just come in and get a cup of coffee and find community. Our navigators [addiction counselors] are here saying, ‘Do you want to try treatment?’ If you say no to treatment six times and they ask a seventh time and you’re ready, we’re there to support you.”

But people on the streets of Kensington told NPR the safety net currently in place to help them escape severe addiction still feels dangerously thin.

‘Our system is not built [to help] that person’

“I relapsed like a week ago, but I am trying to stay clean,” said Tracy Horvat, who has lived in the neighborhood much of her life, often while using street drugs. She said fentanyl might have killed her naloxone weren’t so widely available. Asked what she would need to beat addiction, Horvath said she desperately wants a safe place to live: “I want stable housing,” she said.

Front-line responders say the need for housing, health care, counseling and drug treatment services in neighborhoods like Kensington already feels overwhelming.

Another complexity is the growing array of high-risk street drugs being sold in places like Kensington.

Christopher Moraff who tests illicit drugs in Pennsylvania with the nonprofit group PA Groundhogs said drug gangs increasingly dilute fentanyl with animal tranquilizers such as medetomidine and xylazine.

“Xylazine, which causes pretty severe wounds on people, requires a large amount to be fatal,” Moraff said. “What we’re seeing is many unresponsive people who are not in respiratory distress.”

Researchers and doctors say these substances appear less lethal but are still highly toxic, causing a new range of severe long-term ailments.

“We say this person is ready to go for substance use treatment, but they have an amputation or they have an open wound or they have incredibly high blood pressure,” said McLoyd, who leads Philadelphia’s overdose unit. “Historically, our system is not built for that person.”

Still, she said Philadelphia has made progress creating a network of services and support here that didn’t exist a decade ago. “There’s one of our partners, the Kensington Hospital wound care van,” she said, pointing to a truck parked under the elevated train track.

“We just work our best to help people be well. We keep trying.”

On many blocks, NPR did see signs of this growing public health response: field health care teams, charitable groups offering meals, a warming station, a special police unit trained in addiction response, and a group from a local university dispensing buprenorphine, a long-term medication that reduces fentanyl cravings.

Prevention Point was also offering clean needles at a syringe exchange held in the courtyard outside their building, a program, designed to help reduce the spread of disease.

“I was addicted to heroin and then fentanyl,” said Scout Gilson, one of the organization’s harm reduction workers, who was also handing out clean clothes to people.

Gilson said she knows firsthand how complicated the long-term health impacts of drug use can be, everything from mental health challenges to lingering skin wounds.

“I’m covered in scars, heavily scarred. I’m pretty much marked for life as a drug user,” she said.

Despite the challenges, she described this as a hopeful moment in Kensington, with people living longer and gaining more chances to enter recovery, heal and rebuild their lives.

“It’s not just pointless suffering,” Gilson said. “There’s things that are happening, people doing the work, and there’s obvious ways that we can improve [people’s lives] and figure out how we can do that.”

People here told NPR that neighborhoods like Kensington won’t be transformed overnight. It took years to slow and then reverse wave of fentanyl deaths. Public health experts, front-line care providers and people living with addiction said helping survivors will take more resources — and a lot more time.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.