‘Feeling is healing’: Mental health summit in Olney uses hip-hop as therapy

One goal of the mental health summit is to dispel the stigma associated with mental health issues in black communities.

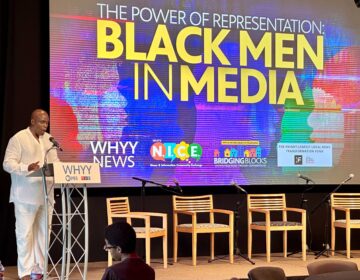

More than a dozen teens participate in a mental health summit organized by TEAM Inc. at The Kingdom Life Church Ministries, on Saturday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

Ronald Crawford may be of an older music generation, but he knows how to connect with Philly kids and teens to broach difficult topics: through modern hip-hop.

In the classroom of the Kingdom Life Church Ministries in Olney, Crawford played Philly rapper Meek Mill’s song “Trauma” through his iPhone and mini speakers. He instructed the roughly 20 kids in attendance to listen closely to the lyrics.

“What traumatic experiences did Meek talk about in the song?” Crawford, a therapist based in North Philly, asked the room.

Some of the answers included Mill’s negative experience with Philadelphia’s criminal justice system, using drugs, and witnessing loved ones injured by gun violence.

“Trauma is something that takes a toll on you,” one student answered.

Crawford was running a breakout session focused on hip-hop as therapy during the “Feeling is Healing” mental health summit on Saturday, hosted by community mentoring nonprofit TEAM Inc.

Taj Murdock, the founder of TEAM Inc., said the summit was focused on helping young people identify the negative feelings they’re experiencing, and then finding ways to cope with them.

According to a 2018 survey from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, African-American youth who had a major depressive episode received treatment, compared to 45% of white youth.

Murdock also hopes the mental health summit can dispel the stigma associated with mental health issues in black communities. It’s something Murdock, who was a professional licensed barber for 25 years, experienced firsthand.

During the early stages of his career, Murdock had the chance to work with many A-list celebrities, and NBA and NFL athletes. He was at the top of his game.

“Coming from the inner city like a lot of these young people are, I was blessed to be successful, but I never dealt with the trauma I had from childhood,” Murdock said. “My father not being in my life, dealing with a lot of substance abuse in my family. I took on those same characteristics when I was trying to mask that pain I felt over time.”

Murdock said he got to a point in his life where he couldn’t handle the emotions he was holding in anymore, and went down a path of destructive behaviors, eventually ending up incarcerated.

“From the outside, everyone sees a success,” Murdock said. “But again, me ignoring those feelings, me suppressing those feelings, that’s what it was in the first place.”

Today, it’s important for him to break that cycle for the young people he mentors through TEAM Inc. Murdock wants to inspire parents and community leaders to ask young people about mental health before they bottle up their emotions.

“As much as we want to push our young people toward being successful, we gotta talk about how they’re feeling,” Murdock said. “We gotta peel back that onion, peel back some of those layers and really figure out what’s going on at the core.”

For therapist Ronald Crawford, implementing hip-hop into his work with young people is crucial.

He says many of the people he works with express their identities, whether through the music they listen to, their language, or clothing, through hip-hop culture. For some young people of color who feel nervous about talking about depression, anxiety or PTSD, using hip-hop makes the therapy more culturally relevant to them.

“One of the things I notice is that people of color are overrepresented with statistics of violence and incarceration, but a lot of their emotional needs are unaddressed,” Crawford said. “If people get therapy, they can understand conflict resolution, they can understand dealing with anger, and that can prevent some of the violence.”

Saturday’s programming was geared mostly toward kids and young adults. Crawford said starting mental health awareness as young as possible can better people’s emotional intelligence down the road.

Zion Patton, 16, attended Crawford’s hip-hop session. He said for him personally, analyzing hip-hop lyrics that deal with mental health helped more than regular therapy.

“I think it’s more effective if you hear it through lyrics, especially because as a young person, you can relate to the lyrics more and it’s a more fun way of talking about your problems, hearing it from someone else,” said Patton, who lives in Southwest Philadelphia. “It’s a good way to talk about your problems.”

Among the other breakout sessions at Saturday’s summit were emotional intelligence for 9- to 13-year-olds, “I’m Alright,” which discussed verbal blanket statements like “I’m OK,” and how to dig deeper, and “Tell Me How to Fix It,” which gave practical solutions to dealing with a mental health problem once it’s been acknowledged. Other breakout leaders included Dr. James Jones, a psychiatric consultant at Philly-based therapy nonprofit Gaudenzia, Tamekia Young, a licensed youth and family counselor, and Charlotte Andrews, a licensed psychotherapist and behavioral specialist.

During Saturday’s wrap-up, Murdock asked the young attendees sitting in the church’s pews what they learned during the day. Many of the responses were introspective and insightful.

“Life means more than what you think.”

“There’s always another option.”

“Life is more than pain.”

Murdock said this isn’t the last mental health summit he plans to host. He wants to go citywide with the program, hopefully with an event in the spring. But he is also considering something during the holidays, to help people who may be feeling somber about lost loved ones, or facing other family issues.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.