‘Drawing with steel’ artists turn scrap metal into sculptures

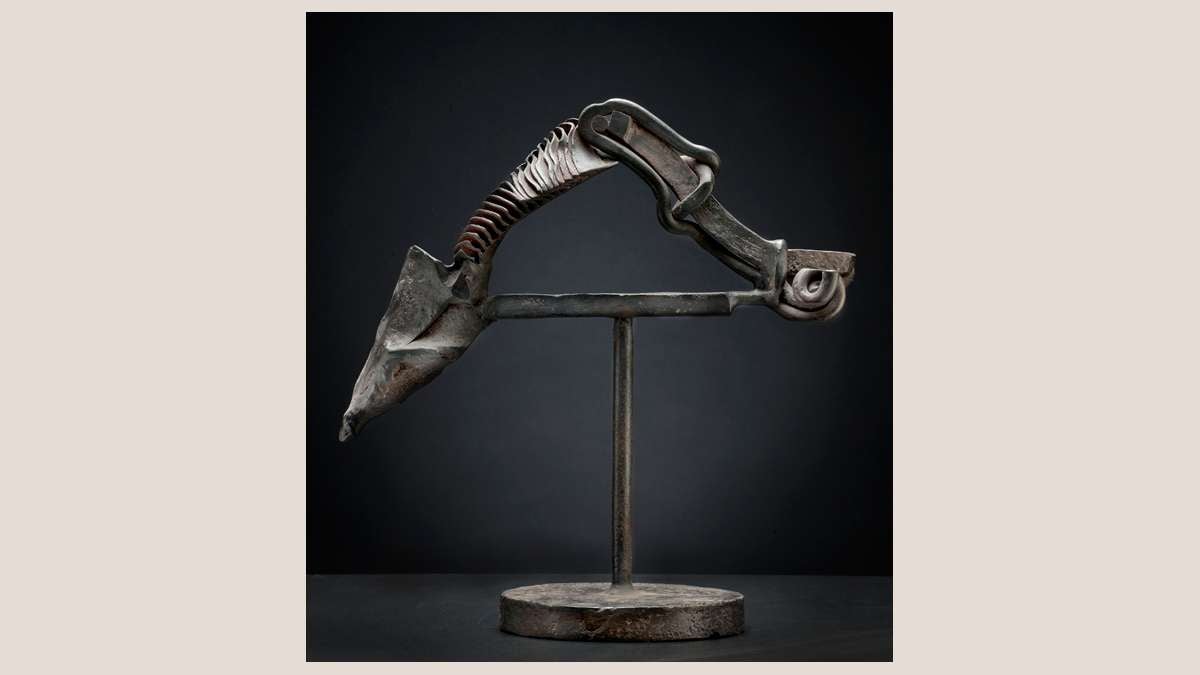

A pile of distorted metal, a frazzle of cable – sculptor Karl Stirner finds beauty in detritus. Still working at 92, he salvages metal from Bethlehem Steel, the junkyard, shipyards, auctions, flea markets or the street. He is a master of transforming hulking pieces of metal, and what he does has been described as drawing with steel.

Karl Stirner: Decades in Steel is on view through Sept. 20 in the Museum Building at Grounds For Sculpture. Even if the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, it branches out on its own. Upstairs in Jonas Stirner: One, a viewer can observe the similarities and differences between a father’s work and a son’s.

Each piece was built with Stirner’s own hands – no machines or studio assistants did the work for him. “He loves the raw quality of the material,” says Grounds For Sculpture Chief Curator and Artistic Director Tom Moran. “He is aware of art history but doesn’t seem to care about it. His preoccupation is with volume, flatness and form.” Rather than paint the surface, he allows the metal to oxidize naturally, or he may heat, grind and polish a surface.

Stirner is attracted to pits and cavities, and the contrast of smooth and shiny. Using tools to cut and shape steel like butter or dough, he finds the diamond in the rough. New forms take shape as he rearranges metal – he can render the hardest of surfaces to take on the folds of flesh — and yet there’s still a call and response to the original object. “I love every kind of object,” he says, admitting a preference for things that are old, with history and patina. He is interested in the relationships between the parts and the whole, and hopes viewers will unravel the work’s message themselves.

One looks like a fish skeleton, another a dancer, and yet another like a bird with a long droodle of a trunk. Some look like the human body. “What you see is what you see,” Stirner says.

Born in Bad Wilbad, Germany, in 1923, Karl was 4 when the family moved to Philadelphia. He grew up fascinated by his parents’ work as jewelers and precious metal smiths, as well as frogs, birds, insects, crystals and shells.

A self-taught artist, Stirner opened a machine shop after serving in World War II, which led to a metal arts studio, designing and making contemporary metal furniture, architectural sculpture and ornamental panels. Soon he was teaching at Moore College of Art and became the director of the metal department at Tyler School of Art at Temple University. From there he opened Karl Stirner Ornamental Ironworks in Germantown.

After a solo show at the Delaware Museum of Art in 1959 and a show of 52 engravings at the Philadelphia Print Club in 1963, Stirner’s sculpture was put on hold while he raised a family and pursued real estate development, but the interruption fueled his drive, and soon he produced so much work, he needed new studio space.

In 1983, he bought a 38,000-square-foot factory building in Easton, Pa. On the first floor is the shop where he works; the second floor is his “showroom”; and on the third floor, his living space, he is surrounded by a museum’s worth of collections, from pre-Colombian and ancient Chinese to Greek, Roman and American Indian art. Stirner developed a love for primitive art while stationed in New Guinea.

Called “the godfather of Easton’s art renaissance,” Stirner is credited with the revitalization of the city at the confluence of the Delaware and Lehigh rivers. He brought artists by the busload to see Easton’s prospective studios, where they could produce large works from recycled or found material. Easton’s 2.5-mile Karl Stirner Arts Trail was named in his honor. The bike-friendly trail has art along the walkway.

There are dancers and birds in the son’s work, as well, but the metal is touched in a different way. When father and son get together, they visit junkyards and critique each other’s work.

Like his father, Jonas is self taught. He served as assistant to Robert Rauschenberg from 1997 to 2006, and from Rauschenberg he learned to accept accident, says Curator Moran. A steel canvas with rough ragged edges, from which hangs distressed but ordered chains, has more spontaneity than the work of his father – it is labored but not polished.

“He has these pieces everywhere in his yard in Ft. Myers, Florida,” says Moran. “His home is on one level with a foyer that is a gallery, and the works are in his landscape too. The Florida air gives it a speckled patina.” Like his father, the son has a talent for assembling things. The Florida building boom left behind interesting rebar and concrete building fragments.

“He knows when to stop,” says Moran. Jonas keeps the original flaking, peeling rust and yellow and red paint. “The mystery of the Stirners is, you never know what the parts originally were.”

Karl Stirner: Decades in Steel and Jonas Stirner: One are on view at Grounds For Sculpture through Sept. 20, 2015.

__________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.