Fabric museum exhibit asks the big question: Who determines when something is art?

Listen

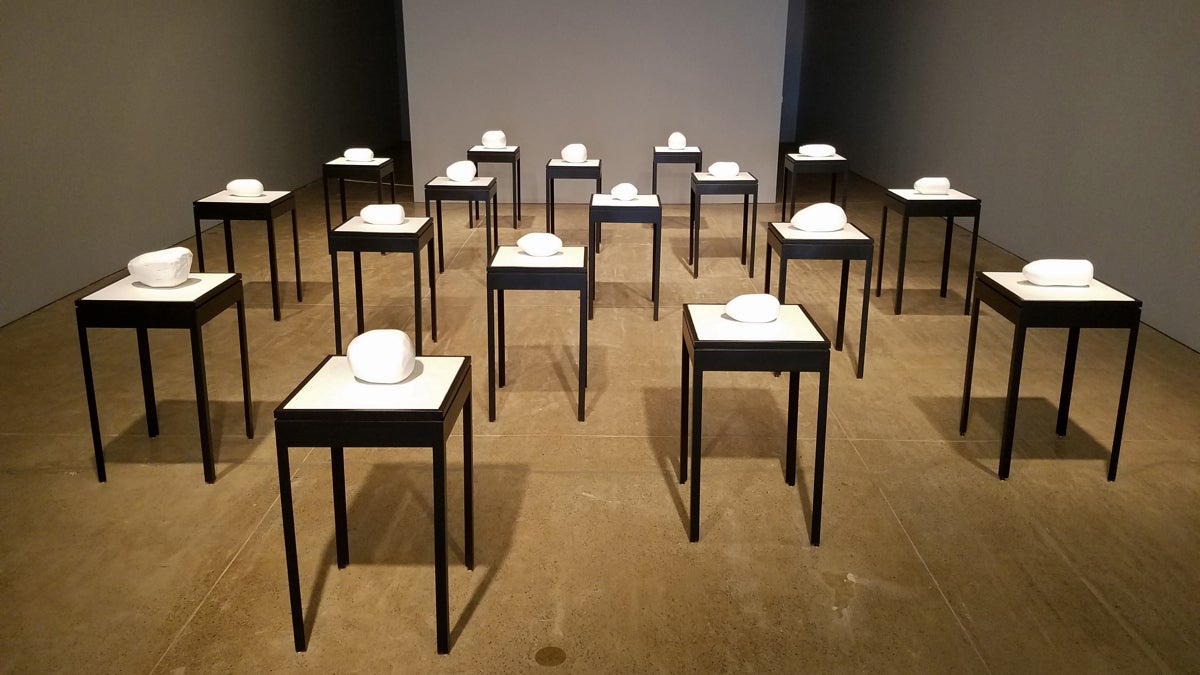

Lenka Clayton's conceptual piece "Sculpture for the Blind, By the Blind" at the Fabric Workshop and Museum. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has become the subject of a new artwork at another museum.

The Fabric Workshop and Museum commissioned an artist to make a work based on curatorial practices at the art museum.

The residency program at FWM gives artist carte blanche to do whatever they wish, regardless of its relationship to fabric or textile. Conceptual artist Lenka Clayton of Pittsburgh was drawn to the art museum’s extensive collection of work by sculptor Constantin Brancusi.

In Gallery 188, known as the Brancusi Room, the museum exhibits “Sculpture for the Blind,” a smooth egg-shaped piece of white marble about the size of a rugby football. It’s under a glass vitrine, so it cannot be touched — not by a blind person nor anybody else.

“Which, to me, is an incredibly beautiful, absurd situation,” said Clayton. “The quite understandable logic of the museum — to keep that artwork safe — collides with the logic of the artist, or the title of the artwork, to create this beautifully absurd situation of a sculpture for the blind that exists only for the sighted.”

It’s unclear if Brancusi ever intended his piece to be handled publicly. The documentation of the sculpture suggests it may have once been displayed inside a bag, and viewers would have to reach inside to experience the piece through touch — but that account is apocryphal.

“Artists throughout the early 20th century used titles as a way to carry the viewer’s mind in certain directions — whether poetic or conceptual,” said John Vick, collections project manager for the art museum. “The idea of ‘Sculpture for the Blind’ conveys an idea of touch, whether or not you are able to touch it.”

Clayton was commissioned by the Fabric Workshop and Museum to create a work in response to the Brancusi sculpture and the way it is displayed.

She gathered 17 blind people, described “Sculpture for the Blind” as best she could, and asked them to re-create it based on their understanding of the piece.

The result comprises 17 interpretations of “Sculpture for the Blind,” by the blind, rendered in plaster. Some attempted to be faithful to Brancusi’s shape, some clearly took liberties with its imperfections. Clayton’s description of a tiny crease in the marble of Brancusi’s work became great gouges in the hands of some of the blind artists, aggressively destroying the egglike harmony.

“You can touch all of them,” said Clayton, gliding among the 17 pedestals on the second floor of the fabric museum.

The other half of the room has a different, but related installation. While Clayton researched the original Brancusi sculpture, she came upon a letter written to the art museum in the 1970s from a man who said his great-grandfather, an amateur artist, sculpted an egg similar to Brancusi’s. That egg was sitting on the desk of the letter-writer.

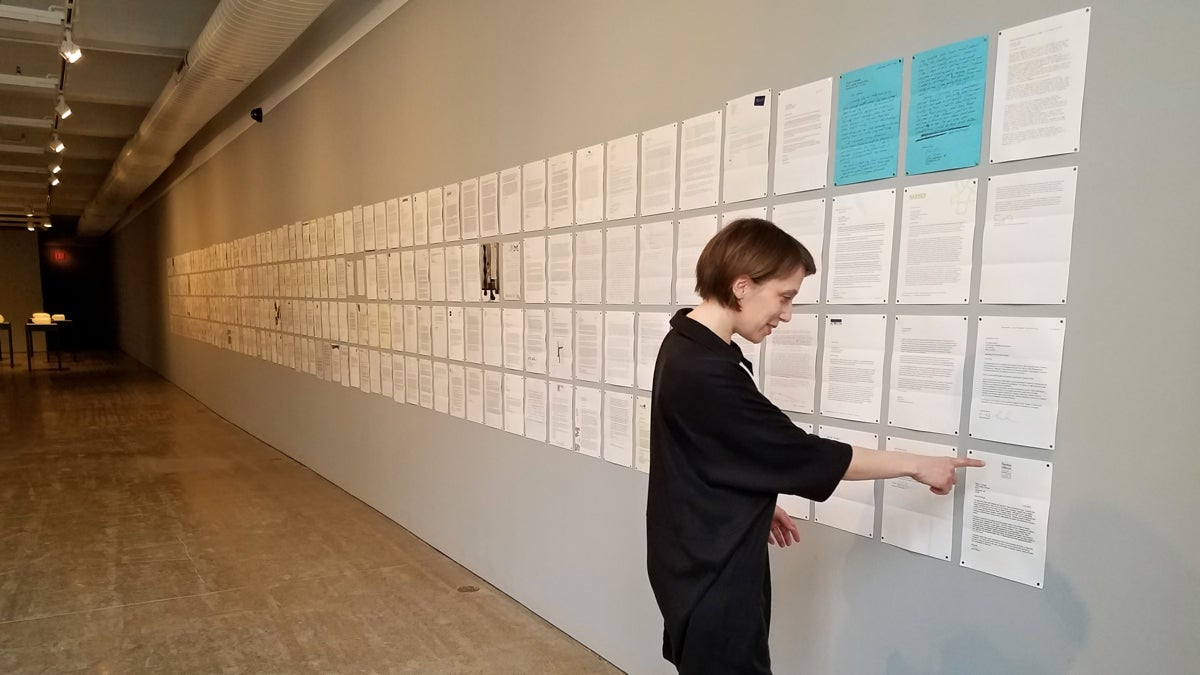

Artist Lenka Clayton, with her conceptual piece ”Unanswered Letter” at the Fabric Workshop and Museum. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

Artist Lenka Clayton, with her conceptual piece ”Unanswered Letter” at the Fabric Workshop and Museum. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

In the letter addressed to then-curator Anne D’Harnoncourt, who would go on to be the museum’s director, this query was posed: Why is Brancusi’s egg worthy to be in a museum, but his great-grandfather’s egg is not?

“A very poignant 40-year-old letter,” said Clayton. “I did some research, it was never answered. A question has been asked, nobody has answered it yet.”

To fill the void, Clayton sent the letter to 1,000 museum directors and curators, and asked them to provide an answer. In the spirit of the project, 179 responses came back, ranging from the very curt to the very whimsical. All are fixed to the wall in a long grid.

“The question of what makes a work of art suitable for a museum certainly remains relevant,” wrote Eric Crosby, curator at Carnegie Museum of Art. “However, today we find ourselves consumed by a very different, though related question: Namely, what makes a museum suitable for art?”

The question of why some things are considered artistic and some not is one museums grapple with constantly. The question may come up more frequently at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as it is a major repository of work by Marcel Duchamp. The early modernist challenged systems of art appreciation, famously presenting a second-hand urinal as the Readymade sculpture, “Fountain.”

“You do get people asking, ‘Why is this art?'” said Vick, describing visitors turning the corner from the museum’s 19th century galleries into its 20th century galleries.

The answer is always changing; sometimes, it’s confrontational. While there is no rubber stamp to approve some lucky objects as art, and unlucky ones as not-art, major institutions like the Philadelphia Museum of Art have the power to collect and display works deemed important.

“You have art lovers and you also have art skeptics, and the whole range in between,” said Vick. “Skepticism makes you think more. It makes you look more closely. It makes you do all the things that can lead to an experience of art that is very rewarding.”

Vick expects the questions to be raised with more frequency in the coming months. On April 1, the museum is preparing an exhibition based on the debate surrounding Duchamp’s “Fountain.”

He said the date of the opening is purely coincidental; nevertheless, the museum is leveraging the irony of it, all the same.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.