Explainer: William Penn Foundation’s Delaware Basin watershed project

The Delaware River. (Image from Investing in Strategies report for Wm Penn Foundation)

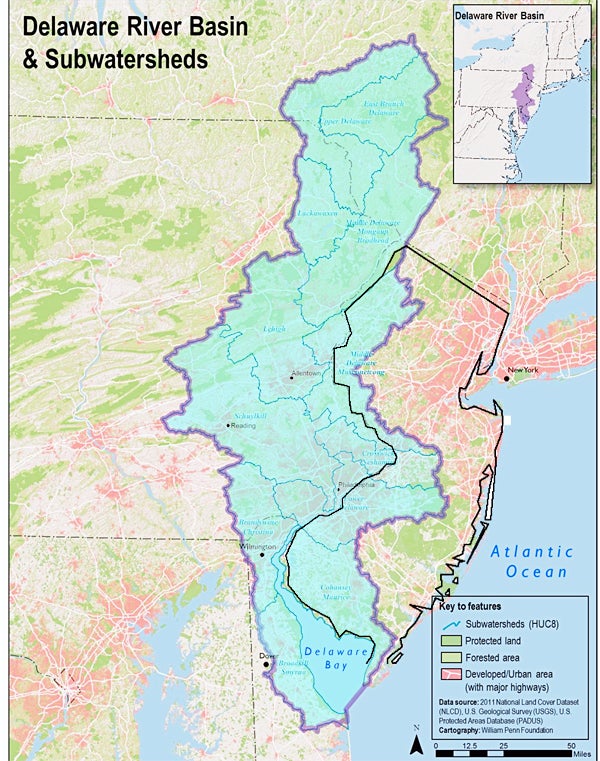

Delaware River Watershed Project

An ambitious program to protect and restore water quality in eight areas of the Delaware River watershed from upstate New York to the Delaware Bay, including two in New Jersey – the Highlands and the Pinelands.

Using $35 million from the Philadelphia-based William Penn Foundation (full disclosure: the William Penn Foundation is a major funder of NJ Spotlight and provides WHYY/NewsWorks funds to cover watershed issues), the program buys land to prevent development, negotiates long-term agreements with landowners to permanently prevent development, works to eradicate invasive species, and educates citizens to help eradicate sources of pollution like leaky septic systems.

The initiative, launched in April 2014, brings together about 50 environmental groups – ranging from national organizations like The Nature Conservancy to local, single-issue groups like the Musconetcong Watershed Association – to share their expertise and work collaboratively in specific areas of the watershed.

Why was it launched? To protect drinking water sources for the 15 million residents of the Delaware Basin, including cities such as New York, Trenton and Philadelphia, by preventing contaminants like farm waste, storm water and runoff from residential lawns from flowing into the headwaters that feed the main river and into the river itself.

It also aims to protect endangered species that depend on habitat – some of it globally significant — threatened by development, industry or agriculture.

It also aims to protect endangered species that depend on habitat – some of it globally significant — threatened by development, industry or agriculture.

The work complements that done by the Delaware River Basin Commission, an interstate body that regulates water quality and supply in the watershed lands of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

The foundation and its partners wanted to create a coherent approach to water protection in an area that covers four states, and multiple counties and towns, and where a host of nonprofit organizations were working, although sometimes in isolation from each other.

Although some progress has been made in cleaning up the river and its tributaries, the watershed is seen as a “tipping point” because of continuing pressure from farming, development and contaminated runoff from an increasing area of pavement.

What has it achieved so far? Officials say it’s too early to show clear evidence of improving water quality less than two years into the project but point out that early work such as building up riparian buffers and testing existing water conditions has taken place, laying the groundwork for improving water quality in coming years.

Across the watershed, more than 14,000 acres have been purchased by 18 land-protection projects, using $4.5 million in funds from the foundation and its partner in landscape- protection projects, the Open Space Institute. The funding has leveraged a further $41 million in private funds. Another 5,600 acres have been restored using best-management practices for stormwater drainage and agricultural runoff via 30 projects using $3.9 million in funds from the foundation and its partner in restoration projects, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, leveraging another $10 million.

In New Jersey, state and local groups connected with the initiative have participated in projects ranging from land purchases to the repair of riparian buffers to the mapping of lands vulnerable to damage from off-road vehicles.

In the Highlands, projects include one by the Land Conservancy of New Jersey which expects to close this summer on the purchase of 2,500 acres in the Lubbers Run sub-watershed, protecting about 8 percent of that area. In Hackettstown, the New Jersey Conservation Foundation will add to the Mt. Rascal Preserve in a purchase that will protect a headwater feeding the Musconetcong River where trout breed.

In the Pinelands, projects include mapping the location and extent of damage caused by off-road vehicles. . The initiative has awarded about $10,000 over a three-year period to help pay for the mapping. Off-roaders destroy large areas of the fragile environment, said Christopher Jage, the New Jersey Conservation Foundation’s assistant director for South Jersey, who is an active advocate for restricting the vehicles’ access to the Pinelands.

But more important than the financial support, he said, is a new wave of collaboration that has been activated between the NJCF and 13 other South Jersey environmental groups that are participating in the initiative.

The program has sought to combine the efforts of groups that previously were more likely to work independently of each other, and to individually seek money from the foundation.

All of the groups are now working together on programs that are more likely to avoid duplication and benefit from each other’s ideas, he said.

“What Penn was finding was that there probably would be a benefit if there was a little more alignment of these grants and collaboration,” he said. “Rather than having 14 organizations in their offices writing these proposals, they sat us all down together.

“That’s the special sauce that came out of this,” he said. “It’s not like we didn’t collaborate before but we never did it in such a deliberate manner, especially when it comes to writing grant proposals.”

Land-protection projects in New Jersey so far total an investment of $1.1 million, of which three projects totaling $400,000 have been closed and $700,000 worth of projects are pending, according to Peter Howell of the Open Space Initiative.

Are there some local examples? The Wallkill River Watershed Management Group in Sussex County has planted more trees, built more rain gardens to contain stormwater runoff, and educated more farmers about limiting the runoff of animal waste – all as a result of increased funding and more cooperation with local groups.

Nathaniel Sajdak, watershed manager for the Wallkill group, which is part of the Sussex County Municipal Utilities Authority, said he has benefited in particular from the collaboration of other conservation organizations.

“By being invited to participate in the initiative, we were able to start interacting with a whole host of other partners which has just provided an incredible amount of resource sharing, information sharing, technical capability,” he said. “It’s getting partners to work together in a way that hasn’t happened before.”

Sajdak declined to specify how much extra funding he had received as a result of the initiative but said it has enabled him to significantly increase the natural areas that he protects, and to leverage other sources of funding that would not previously have been available.

“It allows us to cover more ground, work with more local entities, and look for larger project areas,” he said.

By planting more trees along river banks, for example, Sajdak and his team are able to provide more shade cover for the water, and to reduce sediment loss during storms.

Such projects won’t result in an immediate improvement in water quality but will do so in coming years, he said.

“Is it improving water quality overnight? No. But is it leading to overall better health down the road? Absolutely,” he said.

In the Upper Paulins Kill watershed in Sussex and Warren counties, The Nature Conservancy is helping to restore two and a half miles of riparian flood plain, with the aid of funding from the initiative, said Eric Olson, the group’s Delaware River and Bay Project director.

Long-term dedicated funding has allowed the conservation group to expand its efforts to educate people who may be able to help reduce levels of contaminants such as phosphorous in the waterway, Olson said. Since receiving extra funding, he has been able to expand the riverbank area covered from less than a mile, and to extend his education efforts to local businesses.

At the Musconetcong Watershed Association, covering Warren and three other counties, participation in the initiative has allowed the nonprofit to identify bacteria in the river, and to step up efforts to educate local people about making sure their septic tanks work properly, said Beth Styler Barry, the executive director.

Barry said she now has about $100,000 over three years to spend on laboratory analysis by Montclair State University of river water samples.

“We already knew there was bacteria in the river but with Penn funding we were able to take the next step with DNA testing that helps you to understand the source of that bacteria — people or animals,” she said.

“Without doing that extra step in your analysis, you might put forward a program or a lot of funding that keeps livestock out of the river and then you find out that it was a human problem anyway and it would all be for naught,” she said.

The group’s work on local water quality has also been aided by collaboration with the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, which is heading up water monitoring throughout the watershed initiative.

“When it comes to thinking deeper and harder about a problem like what is the actual source, we can now turn to the Academy of Natural Sciences, and we would not have had that door open to us before,” Barry said. “Would my group have been able to afford this? No.”

The Academy is leading scientific sampling in places like the Musconetcong River, and is monitoring fish, macro-invertebrates, salamanders, algae, chemistry and habitat to gauge water quality, said Carol Collier, the Academy’s Senior Advisor for Watershed Management & Policy.

After almost two years working together, the initiative’s participants are more unified, Collier said.

“It started out like a lot of spinning tops, like a lot of different efforts, but after about a year, people settled in,” she said. “The cluster members are learning how to work better with each other; they used to be competitors for funding and now they’re working together. It’s really clicking along now.”

_______________________________________________

NJ Spotlight, an independent online news service on issues critical to New Jersey, makes its in-depth reporting available to NewsWorks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.