What can we learn from George Orwell today?

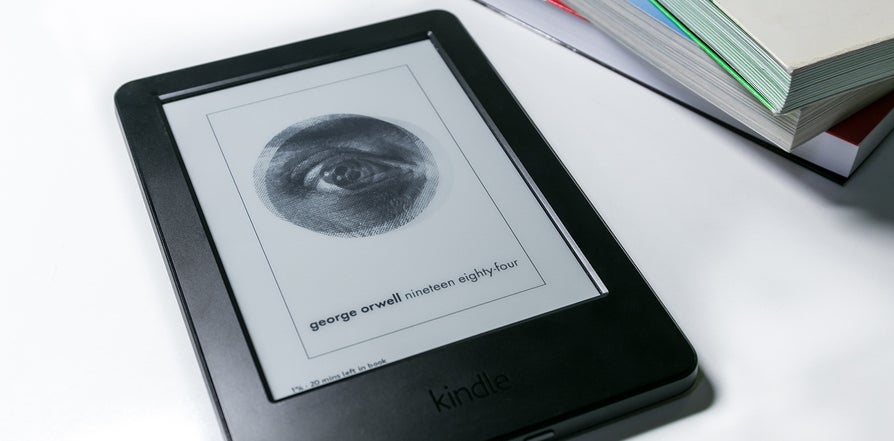

The cover of 'Nineteen Eighty-Four' by George Orwell, E-book version on Amazon Kindle. (keysersoze27/Big Stock Photo)

There is much to be learned from George Orwell’s classic novel “1984,” written in 1949, which has suddenly jumped again to the top of bestseller lists.

It’s no wonder — in today’s political world of alternative facts and fake news, the author’s coining of the term “Newspeak” has particular resonance. In the novel, Newspeak is a language designed with restricted vocabulary and thought. For example, it allowed for no word meaning “bad” — only “ungood.”

“Good prose is like a window pane,” Orwell wrote in his essay “Why I Write,” and his is an enduring lesson for those who aspire to express their thoughts clearly.

Alas, that aspiration is seldom realized among the obfuscations and evasions and even outright lies that characterize much of modern political discourse. In “1984,” the story of a dystopian future society, Orwell wrote about the mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence as the most marked characteristic of modern English prose which, he says, consists less and less of words chosen for their meaning and more and more of phrases tacked together like sections of a prefabricated hen house.

He gives a wonderful example of linguistic decay, starting by quoting the well-known verse from Ecclesiastes:

‘I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise nor yet riches to men of understanding nor yet favor to men of skill but time and chance happeneth to them all.’

This he turns into modern English thus:

‘Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.’

Can’t you just hear White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer using that cloudy phraseology? Maybe the oft-repeated sentence “Big brother is watching you,” in “1984,” could have been tailored to Spicer’s brand of orotundity, or indeed to who might be watching him?

Spicer’s multiple evasions and prevarications began at the start of his tenure with an assertion that the size of the crowd at president Trump’s inauguration was the largest ever an exaggeration easily disproved by photography.

I was privileged to interview Orwell’s friend and contemporary, the journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, when he was in his 80s. He recalled his friendship with Orwell, saying “he was an extraordinary chap … his three or four volumes of collected journalism are brilliant; they stand up today. So lucid.”

In his collection of essays, “And Yet,” Christopher Hitchens discusses Orwell’s lifelong hatred for all forms of censorship, proscription, and blacklisting. And in his book “Why Orwell Matters,” the late British author and polemicist points out that “what Orwell illustrates, by his commitment to language as the partner of truth, is not what you think but how you think.”

In a prescient comment on today’s politics, he notes that “in the late 1940s, a dystopian novel based on the notorious horrors of National Socialism would probably have been very well received. But it would’ve done nothing to shake the complacency of Western intellectuals concerning the system of state terror for which, at the time, so many of them had either a blind spot or a soft spot.”

Much the same line of thought might be applied to today’s intellectuals, many of whom seem blind to Trump’s Russian connection, to what Steve Bannon calls the dismantling of the administrative state, or to the denial of global warming.

Orwell said that, at age 50, everyone has the face he deserves. Alas, he was never able to see if that held true for him. He died of tuberculosis at 47. In that brief lifespan he produced an enormous volume of essays and novels, including “1984,” a chilling portrayal of the dehumanizing effects of totalitarian society.

What might we learn from George Orwell today? Certainly that truthfulness and clarity are vital components of good communication. In today’s politics, those virtues are sadly lacking; in Trumpism, they are practically nonexistent.

—

David Woods, Ph.D., is a Philadelphia-based medical writer and editor. A former editor in chief of the Canadian Medical Association Journal, he is the author of four books and more than 200 articles, editorials, and reviews in peer-reviewed health care publications.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.