The shame of my father’s racism

It took me years to talk about the racism perpetuated by my father in public settings. I was ashamed and embarrassed by him most of my early life.

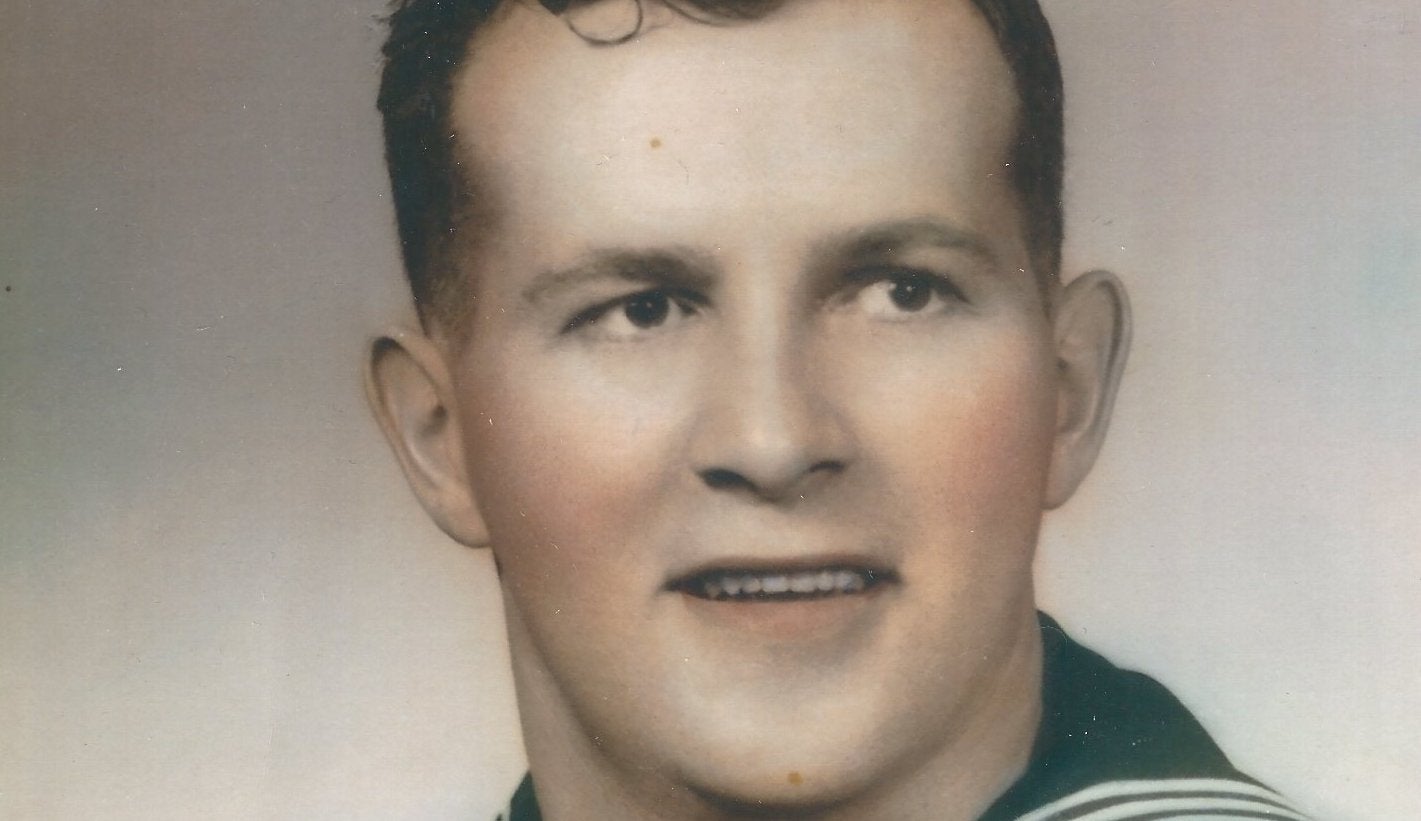

The author's father (Image courtesy of Marybeth Gasman)

Join WHYY on Monday, May 22, for Courageous Conversations: Race at the Crossroads, a public discussion where we ask “What do we lose when we don’t talk about race, and how could our lives improve if we did?” This event is presented in partnership with WURD, Philadelphia Media Network, and American Bible Society.

—

It took me years to talk about the racism perpetuated by my father in public settings. I was ashamed and embarrassed by him most of my early life. He was angry, verbally abusive, and looked down upon others regularly.

When I was a child, he attempted to fill my head with racist ideas about various people. He used racial slurs regularly and called me and members of our family these same names. As I grew older and began to read books in school, I started to push back at him and challenge his racist notions. He told me I was ignorant.

I couldn’t understand why my father hated most racial and ethnic minorities, even though he had never met any member of these groups in his entire life. His hate was deep and angry, and he used “evidence” to try to persuade me that whites were better than others. He would tell me that African-Americans “caused riots and destroyed cities,” and point to pictures from the Civil Rights Movement. He left out most of the details. He would tell me that African-Americans were “stupid and preferred to live in poverty,” and point to examples that he saw on television in shows such as “Sanford and Son.” He would tell me how cruel Asian-Americans were, citing their efforts to defend their own nations during wartime. He neglected to tell me about the cruelty that has cut across our own nation both during wars and at times of peace. He would tell me how Hispanics were “lazy and took advantage of the government,” citing stereotypical pictures drawn by whites of Mexican-Americans.

My father was an uneducated man, living in dire poverty most of his life. Instead of seeing the commonalities that he had with others oppressed in our nation and looking for ways to bridge those commonalities, he chose to blame others for his poverty and lack of success. It’s important to note that my father often worked two jobs — one in a lumber yard and another on our small animal and vegetable farm; he also looked for odd jobs to make extra money. However, he could never get ahead, making less than minimum wage in many cases. Instead of hurling insults at the systems that perpetuated poverty, or becoming more active locally to change these systems, he decided to funnel his anger into hate for racial and ethnic minorities.

I spent years trying to change his mind — talking with him, trying to educate him, sometimes yelling at him. I even pursued a career as a professor who concentrates on race and class issues in American society, to better understand the hate that my father held in his heart. However, it wasn’t until my father was older, in a nursing home, and had met someone African-American, that he let go of his hate and our nation’s original sin.

The pathway for my father was friendship, and the eventual understanding that he and his friend had much in common and were equally frustrated with their lot in life. It was at this point that my father confided in me that he was unhappy with his life and chose to blame racial and ethnic minorities — African-Americans in particular — for his pain and failure. It was easier to blame those who so many others blamed rather than take responsibility or fight the systems that had helped maintain his place in society.

My father’s story is one of hope in many ways, because he realized his wrongs, but it is also hopeful for me as a scholar. Many of my faculty colleagues throughout the country don’t believe that we can make progress on racial issues and racism. However, I do — but only by engaging others in conversation and encouraging them to assist in dismantling systems. People dismantle systems, not systems themselves.

I have spent hours upon hours talking to people on planes, trains, in hotels, at conferences, in classrooms, etc. about race and have with each conversation tried to get people to consider the perspectives of others and examine their own biases. When people ask me if I get tired or frustrated by these conversations, I often respond by noting that I worked with and on my father for nearly 20 years, knowing that eventually he would turn a corner. What I realized in the end, however, is that it was not my intellectual ideas that changed him but the friendship of another and my having heart-to-heart conversations in which I listened to him openly. We need to do more listening to each other’s stories to move our nation to a better and more equitable place for all.

—

Marybeth Gasman is the Judy & Howard Berkowitz Professor of Education in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania. She also serves as the director of the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.