Red hot in a green heaven — the day I became a Phillies fan

The late-setting July sun illuminated the canyon of freshly deserted mills on the avenue. Over-sized factory windows coated in senescent layers of dust reflected a copper-tinted hue over the cityscape. Just hours earlier, the area would have bustled with a small army of teamsters unloading trucks to waiting pallets, but by 8 p.m., the district more resembled a ghost town.

As we neared the end of our journey, the void began to give way to a crush of vehicular traffic and pedestrian activity. Both seemed drawn, like moths, to the bright banks of lights emanating from the top of a building ahead of us.

Thick plumes of tobacco smoke hung low over the crowd as people entered the enormous structure through various portals along its enormous walls. At a glance, it could have been confused for one of the many giant manufacturing plants peppered throughout North Philadelphia in the 1950s. A tower topped with a rounded cupola soared six stories up from the corner of the building. It looked more like a structure from a Grimm fairytale than the outside of a baseball stadium.

Sensory overload

My father and I, with thousands of others, were now in the process of being siphoned through the main entrance of this fortress. “Gotta push hard,” my father said as I approached the turnstile and my ticket disappeared into a stranger’s waiting hand. Half of it was returned to me a second later. I had to push twice on the formidable metal barrier to land myself on the inside of Connie Mack Stadium.

“PRO-graaams! PRO-graaams!” a barker shouted. Souvenirs abounded, as did waves of familiar odors — roasted peanuts, popcorn, cotton candy, beer, and over-boiled hot dogs — wafting throughout the structure. Late arrivers like us rushed past the tempting concessions in search of our seats as game time approached.

The Phillies’ late great center fielder and long-time broadcaster, Richie Ashburn, said of the stadium after its demolition in 1976: “It looked like a ballpark; it smelled like a ballpark; it had a feeling and a heartbeat, a personality that was all baseball.”

Shibe Park

Originally named Shibe Park, the stadium opened in 1909. It was a magnificent edifice, an ornate French Renaissance structure replete with a Mansard roof and immense mid-story arches. It was also the first professional sports stadium in the country constructed with reinforced concrete and steel, a fitting monument for the long-time powerhouse Philadelphia Athletics who called it home through the first half of the century.

Shibe was a major trade up from the rickety wooden parks of the prior century that enjoyed limited life spans before invariably burning to the ground. The stonework on Shibe was adorned with various baseball friezes and cartouches with the letter “A” over its portals in honor of the home team — and of course, there was that unique cupula entrance.

The stadium rose at the intersection of two dismal, muddy, and unpaved North Philadelphia neighborhoods known as Swampoodle and Goosetown. The infamous “Smallpox Hospital” was located just block away, which made 21st and Lehigh an undesirable location for any business to put down stakes. Club owner, Ben Shibe, had privately received political assurances that the hospital would soon close its doors, so he quietly began buying up adjacent parcels of land.

Leaving Baker Bowl

For 51 years the Phillies played in a bandbox-sized field called Baker Bowl located just six blocks down the avenue from Shibe. A bizarre hump in Baker’s center field barely concealed an active railroad tunnel that had first claim over the local real estate. When the age of the “live ball” arrived, the ever-hapless Phillies could only watch as opposing power-hitters drove the ball across their Little League distance right field fence and into the train yard across Broad Street. A billboard on the right field wall advertising “Lifebuoy Soap” encouraged one disgruntled fan-cum-vandal to sneak into the stadium late one night and enhance the message with the words, “THEY STILL STINK!”

Baker Bowl was mercifully leveled by a wrecking ball in 1938, and the Phillies and Athletics, both now last-place teams with dropping attendance, became fieldmates at Shibe to cut back on mutual overhead. In 1954, the A’s left town to enjoy an unremarkable 12 years in Kansas City before joining the baseball gold rush to California. The Phillies remained in the rebranded “Connie Mack Stadium,” ironically named in honor of the still-breathing 90-year-old ex-manager and owner of the Athletics whose team had bolted town.

Losing the game; winning a fan

A respectable-sized crowd would come out this night to see a very good Milwaukee Braves team face off against my Phillies. Our tickets were marked “Upper Reserved,” which meant that reaching our seats required ascending a multi-flight, vertigo-inducing open staircase. I began to wonder what any of this had to do with a baseball game. Where exactly inside this immense factory was the field?

“Here we are, section 35,” said my father. We made a right turn and headed down the tunnel toward what appeared from a distance to be a sheer drop into nothingness. I instinctively slowed up, not wanting to step into the abyss — then stared in awe, taking in the most magnificent vista I had ever seen; an exquisite expanse of perfectly groomed green bathed by towers of light that miraculously turned night into day.

Across from us in right field stood an imposing 32-foot-high, solid-metal “spite” fence. It was constructed by the tightwad A’s owner, Connie Mack, to stop homeowners on 20th Street from selling hundreds of their own cheap roof-top tickets to erstwhile stadium patrons. A newly installed 64-foot-high scoreboard (purchased from the Yankees after years of service in Yankee Stadium) stood in center-right field with a Ballantine Beer sign at the top and capped by an 11-foot-high Longines clock. Wisely, the Phillies left their old Lifebuoy Soap sign back on Broad Street.

“Red hots! Getcha red hots!” bellowed a hawker. Wide straps crossed his shoulders in support of a metal box protruding from his waist, while his right hand held a pair of menacing-looking tongs.

“Hungry?” asked my father. I nodded, and he held up two fingers to the hawker and shouted “Mustard!” Two hot dogs rapidly advanced across strangers’ laps and arrived at our seats while a pair of quarters took the opposite route. “I was awestruck by the mechanics of the transaction, which seemed as fascinating if slightly less magical than the self-refilling key lime pie window at our local Horn and Hardart Automat.

The Phils received a standing ovation as they took the field, adulation that belied a six-year downhill dive in the standings since the pennant-winning glory of the 1950 Phillies “Whiz Kids.”

Before I could take a bite from my “red hot,” we were on our feet again, this time for the playing of the national anthem. As the vocalist arrived at, “O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave …,” cheers began to build, reaching thunderous proportions by “… and the home of the brave.”

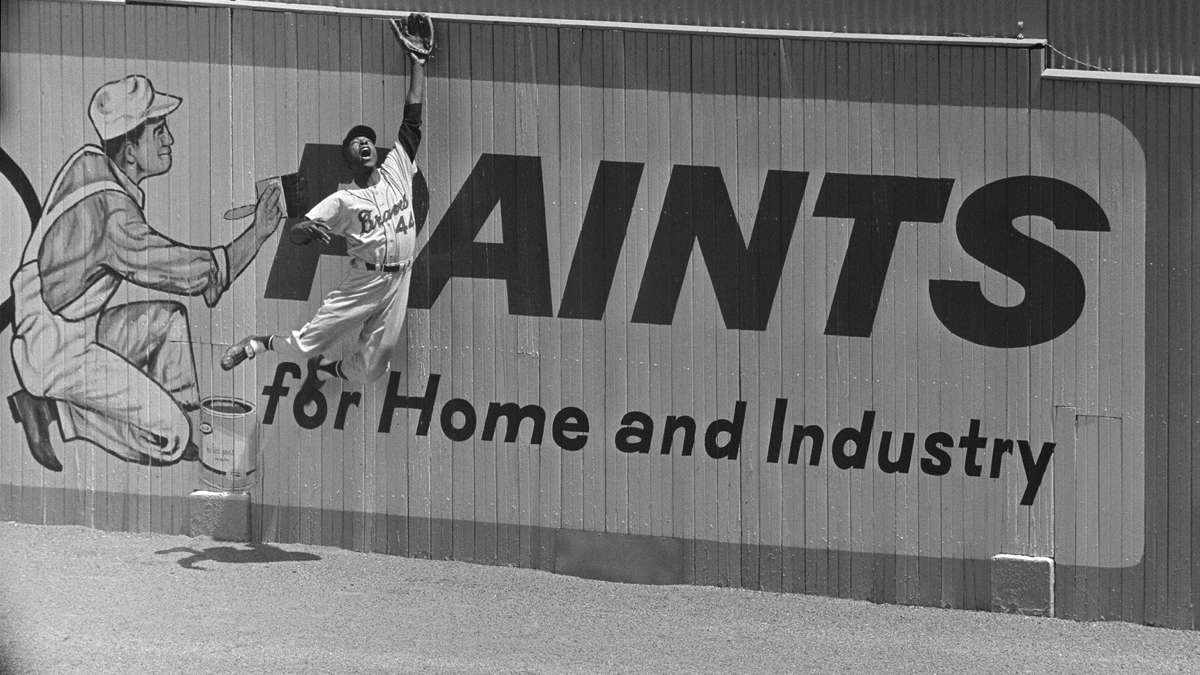

But this evening would belong to a young Brave known as “Hammerin’ Hank,” who quieted the home crowd with one magnificent swing at a very fine Simmons fastball and planted it deep in the upper deck in left. The home team still boasted a few great players — names like Robbie, Curt, Whitey, Del, Puddin’ Head and Granny — all heroes from their 1950 Pennant-winning season, but most of them past their prime. On this evening, my heroes would be no match for the young, talent-laden team from Milwaukee.

It didn’t matter that our seats were located directly behind a view-obstructing steel support column, nor that I remained too much on sensory overload to concentrate on the game. It didn’t even matter that my guys in red pinstripes were crushed by a final score of 10-2.

It didn’t matter, because on that night, I became a baseball fan.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.