How I spent my summer vacation — at Philadelphia libraries

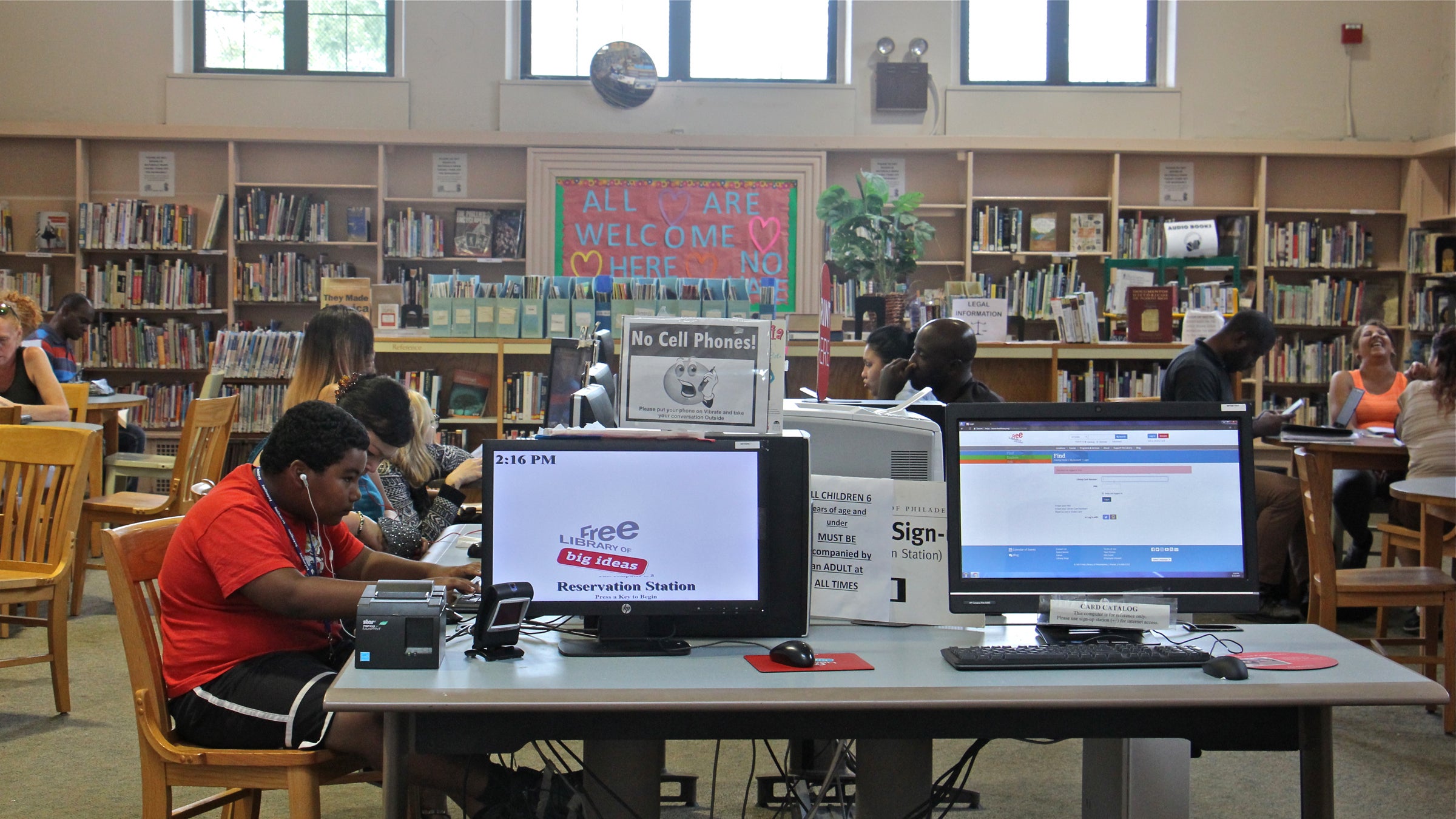

The McPherson Square Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

It might not be the first place you associate with summer in Philadelphia, but the Free Library is an ideal resort: It’s free, close-by, and air-conditioned. There’s a lot to do and room for friends. And that shushing thing? They don’t do that much anymore.

When I was growing up, I’d pedal over to the Northeast Regional branch and peruse the stacks in cool comfort. As an adult I’ve branched out, visiting libraries in unfamiliar neighborhoods, thanks to little tours organized each summer by the Free Library of Philadelphia and the FLP Foundation, which garners private support for the city-funded institution.

I never come away uninspired, both by staff and the services, which go far beyond what was available when I was toting books in the basket of my bike. Today, libraries fill gaps in the social safety net for people who need much more than diverting fiction or help with term papers. Just keeping up with the exponential growth in information and how it is accessed would be daunting, but libraries do so much more.

In every season, a refuge

Philadelphia libraries feed minds, soothe souls, teach skills, and build communities. In low-income neighborhoods, some branches replace school lunch programs in the summer, and are cooling centers for those without air-conditioning. Year-round, they provide essential internet access, as well as sessions on job skills, healthy cooking, starting a business, English as a second language, using technology, and even yoga. For the pre-K crowd, libraries offer creative play, language development, and socialization. For older children and teens, programs to develop STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics) skills attract young imaginations like magnets.

And the branches want to be magnets — evidenced by the effort the library invests in welcoming, well-equipped environments that offer programming tailored to local interests and needs. Philadelphia’s libraries are lifelines, offering stress relief, intellectual stimulation, conversation, information, and in one challenged neighborhood, medical intervention.

McPherson Square

Readers of Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Mike Newall have learned about McPherson Square library, located at ground zero in a very active drug market in Kensington. When faced with repeated overdose incidents, the staff went so far as to stock and administer naloxone to people in distress.

I’d become aware of McPherson Square on a 2016 library tour led by Marion Parkinson, manager of FLP’s North Philadelphia libraries. Standing outside the classical domed building, she’d explained that the library’s park had to be carefully combed each day for used needles. Inside, however, the branch was like any other, colorful and full of life.

Touring in North Philadelphia with Parkinson again this summer, she described the challenges faced by inner city neighborhoods and their libraries. Though the insights can be sobering, Parkinson speaks with optimism and takes obvious delight in her work.

The McPherson Square Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The McPherson Square Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Lillian Marrero branch: Reinvented for the 21st century

On West Lehigh Avenue, we visited the Lillian Marrero branch, one of FLP’s 21st century libraries — total reinventions of existing libraries that bring them up to the latest standards in technology, accessibility, and community-specific programming.

Marrero, which reopens this fall, is the largest of the libraries originally funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie libraries all look like something out of Gone With the Wind — magnificent stone structures that are not the easiest buildings to renovate. The 1906 terracotta exterior was unchanged, except for a large glass jewelbox which now sidles up on the right — a universally accessible entrance. The wall joining old and new structures is protected by a cushion to allow the jewelbox to be removed if necessary.

Inside, the huge main space has been partitioned with right-sized seating and low bookshelves, creating spaces for adults, teens, and children. There will also be space devoted to meetings, computer use, and study.

Widener: Addressing children’s needs

Next was the Widener Branch, in a 2005 building with an abstract, African plain theme. The gazelles were easy to find — on a wall sculpture — but spotting the rest of the menagerie was tricky. Giraffes and an elephant can be found in yellow structural supports and a medium-gray wall. With good timing, zebra-like stripes become visible as sun falls across the carpet. But the hippopotamus, rumored to be in the undulating, dark-brown checkout desk, never quite appears.

Though Widener’s design is whimsical, some programs deal with harsh realities. Neighborhood children with incarcerated parents, for example, come to the library for Skype sessions, enabling them to visit and read with their missing parent. Another program is aimed at diverting young people who’ve had minor brushes with the law through counseling and directed reading.

Widener and the Cecil B. Moore branch, visited last, host the popular Maker Jawn program, in which participants are given a task and materials, but no instructions on designing a solution. That depends on their critical thinking, technical skill, and creativity.

Access is key

Parkinson noted that Widener and Moore habitually are among the leading FLP branches in wifi usage, explaining that the statistic varies inversely with neighborhood income. In the past year, Widener computers were accessed 11,000 times.

At Moore, where computers were accessed 10,000 times, there’s even a way to get wifi when the branch isn’t open: Soofa benches flanking the doors are outfitted with solar collectors and USB ports.

Cecil B. Moore branch: Incorporating play

This fall Moore will install an immersive-play system consisting of child-sized boxes, platforms, tunnels, a miniature stage, and — no kidding — a climbing wall, in which the hand- and footholds will be letters of the alphabet. The structure was planned in consultation with the community and fits nicely with the Words at Play Vocabulary Initiative, aimed at children from birth to age 5. Moore and Widener both offer Words at Play.

The new structure will only add to what Parkinson likes to call “the sound of learning,” which is definitely not the hushed library silence earlier generations remember. From inventing to climbing to hunting an imaginary hippo, Philadelphia libraries are making it harder than ever to avoid visiting, and harder still to leave.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.