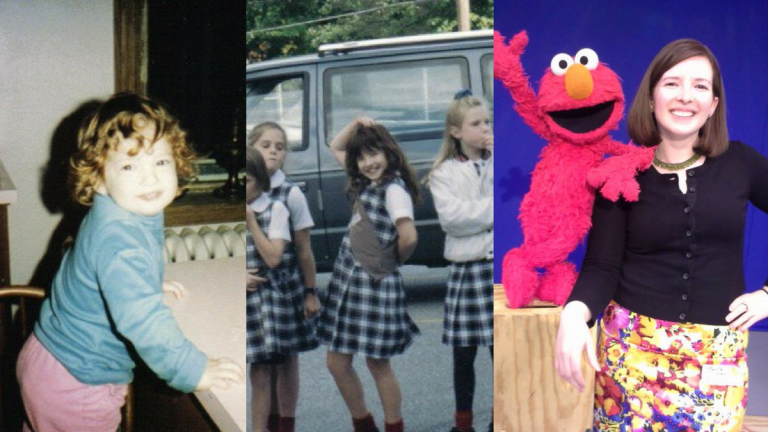

Autism found me, and then I found my voice

Since my diagnosis with autism in 2015 at age 30, a bolder, more outspoken side of myself has emerged.

(Images courtesy of the author)

My usually reliable optimism failed me when Rose began to speak slowly and condescendingly to me. I remained calm as I told her that her behavior made me very uncomfortable and asked to speak with her supervisor. Two 10-minute-long holds later, she hung up on me.

I knew instances of discrimination like this happened, but this was the first time since I was diagnosed with adult autism spectrum disorder that a person had treated me differently because of it. I was speaking to Rose because I called her employer, Orbitz, to request a change to an upcoming trip I had booked, based on accommodations I needed for my disability. When an Orbitz customer complaint representative replied to my email about Rose’s behavior (three days later), they offered me a $100 coupon off my next trip with them. If I didn’t know how Orbitz felt about their customers with disabilities before, I did then.

Since my diagnosis with autism in 2015 at age 30, a bolder, more outspoken side of myself has emerged. I am more open about my needs and my boundaries, and after years of thinking I was stupid and unworthy, I have become a better advocate for myself and others living with autism.

But I have to admit, the years leading up to this point were as illuminating as the diagnosis itself.

‘Coming out’ as autistic

For most of my life, I knew there was something different about me. I struggled to read and tie my shoes while the rest of my classmates were reading chapter books and tying double knots. I had a hard time making friends and found social gatherings to be exhausting and overwhelming. In my adult life, holding down a job was difficult. I tried to fit in by mimicking the behaviors of my colleagues (a strategy that helped me during my school days), but my attempts to connect alienated me even more.

My first realization that these struggles were actually symptoms of a disability happened during a bus ride to New York City in 2013. While paging through one of the alt-weeklies I picked up, I stumbled upon a column about man who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age 40. As I read through his symptoms, I was shocked by how similar his life experience was to mine. If the road to an autism diagnosis was like a 12-step program, this would have been step 1.

In the months that followed, I analyzed other aspects of my life and found more personality quirks that fit with autism: I didn’t speak full sentences until I was three years old, I had trouble reading facial expressions, and I needed routines and was overwhelmed by disruptions to those routines. And I experienced meltdowns, an intense reaction to overstimulation that would take the form of crying or yelling.

By the time I found a doctor who offered diagnostic evaluations for autism in adults in June 2015, I had achieved a level of acceptance and curiosity where I wanted to know for sure, but I also was terrified of how my life might change. Would the people I loved treat me differently when I disclosed my disability to them? Would I have to tell future employers, and would they fire me if I did? Would prospective partners be able to see past my autism and love me in spite of it?

Now, two years later, the answers have arrived through different experiences. I am loved regardless by my family and friends, and I know how to vocalize most communications obstacles I run into with them. My openness about my disability enabled me to find two wonderful nonprofit employers who were committed to my success because a commitment to the emotional well-being and safety of their employees was part of their values and culture. And anyone who can’t love me as a smart, sexy, empowered woman who happens to have autism need not apply.

Encouraging greater awareness and advocacy

While I am open and proud of who I am, I am also very much aware of the obstacles that prevent other adults from receiving a diagnosis and treatment for autism. Statistics and support are more widely available for children than adults. (A 2012 figure from the CDC says that one in 68 children have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, but I was unable to to find a concrete statistic for adults living with autism in the United States.) And medical professionals are misdiagnosing women and girls because the current testing model is based on findings from studies conducted almost entirely on boys.

There are other factors that set my path to diagnosis apart, namely that I am a white woman who grew up in a middle-class household and received a good education in spite of my learning struggles. I have been raised with the idea that nothing is out of reach for me, and I had good health insurance and worked for a supportive employer when I received my diagnosis. The same can’t be said for many individuals on the autism spectrum who are African-American, Latino, immigrant, or transgender, who experience discrimination at a disproportionately higher rate than white cisgender women like me.

People on the autism spectrum are also at greater risk of experiencing domestic violence and sexual assault, and the incidence of suicide in the autism community is alarmingly high. This makes sense when you understand the social isolation and communication difficulties that afflict adults living with autism.

It’s taken me over 32 years to write this essay, and if you’ve read this far, I hope you will finish it with a greater sense of compassion and patience for everyone you meet. Each of us has our own learning style, and we all communicate and process information differently. And each of us is struggling in a way no one else can possibly understand. But facing that struggle in a world where we know we are valued, loved, and accepted makes it much easier to face it and talk about it.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.