A Scranton native’s take on Trump’s commitment to coal

Visitors tour the grounds of McDade Park. Once coal mining terrain, the park is home of the Anthracite Heritage Museum, Lackawanna coal mining tour, and other recreation areas. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

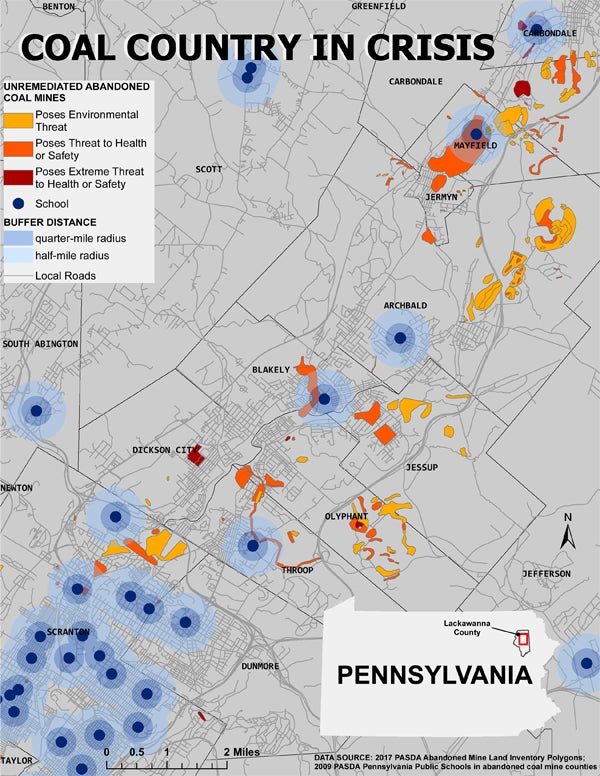

Has President Donald Trump ever heard of Scranton blackfoot? As I watched him posing with coal miners and repeating easy bring-back-jobs slogans, I wondered: Has he ever walked barefoot through the basement of a rowhouse in my hometown’s Hill section, where coal dust coats the walls and floors? Coal mining halted in Scranton almost 60 years ago, but the mess the industry left behind has not been scrubbed from the region.

Growing up in Northeast Pennsylvania was a wholesome affair, but the ghosts of mining were always with us. We’d perch quarters on steel rails built for coal trains, to be flattened by newer locomotives roaring in from the north, carrying modern commodities eastward. We ventured into mile-long seas of culm, a type of impure coal too inefficient to use for producing energy, our sneakers crunching over the hills of grey, lumpy barren landscape that we affectionately called “the dumps.”

I recently romanticized my Scranton upbringing for a co-worker in Delaware, sharing memories of playing in onyx terrain, watching dirt bikes kick up clouds of black dust, and arriving home at sunset with a grey film covering my legs from the hems of my shorts to the straps of my sandals.

My co-worker half-smiled, incredulous. “Really?”

Come to think of it, as kids, we would have dismissed the notion of “clean coal” as a bizarre fairy tale.

In high school, a teacher related a conversation he’d had with an alarmed Scranton transplant.

“That smell? That’s the burning dump! It’s been that way for 30 years!” We all laughed. How was it possible that someone was ignorant of underground mine fires, or the mix of noxious greenhouse gases, carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide, that produced that familiar stench?

What was it that made us so inured, so indifferent to the knowledge that the ground beneath us was a toxic, unquenchable inferno? Or that bygone mining was continuing to cost not only millions in tax dollars, but also area residents’ environmental and physical health?

Last summer, then-candidate Trump’s rallying cry to bring back coal to Scranton had me laughing. The absurdity!

Coal in Scranton is an insider’s thing, both a black joke and a way to feel connected through a shared history, unique to us. We feel a special respect and nostalgia for the hardworking immigrant miners who shaped our heritage. However, ask any resident and they will tell you our one-time claim to fame will not see a renaissance any time soon.

I learned this as a kid, too. On a third grade field trip to the Lackawanna Coal Mine Tour, we walked through eerie, damp mine chambers that illuminated the dark history of child labor, black lung disease, and cruel mine owners who exploited employees. Coalmines were relics, not investment opportunities.

A group walks through a gangway in a former anthracite coal mine as part of the Lackawanna County Coal Mine tour. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

A group walks through a gangway in a former anthracite coal mine as part of the Lackawanna County Coal Mine tour. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Anthracite mining in Lackawanna County began in the 1820s, and brought about technological developments that played a crucial role in the United States’ industrial revolution. By 1900, Scranton became one of the nation’s leading coal producers. The booming industry attracted Slavic, Welsh, and Irish immigrants searching for a better life. The Lackawanna Heritage Valley reported that in the height of production, half of all able-bodied men worked the 110 collieries throughout the greater Scranton region or in a related trade that supported the mines. They extracted an estimated 6,000,000 gross tons of coal each year. Miners unionized after facing inhumane working conditions and mine disasters, which claimed many lives. The mining economy drastically declined during the Great Depression, as America turned to energy alternatives such as natural gas and oil. Companies laid off workers and slashed hours throughout the 1940s. Despite coal’s slow decline, the end of the era came quickly, as a tragic mine flood in 1959 ceased production altogether.

The city has not recovered from coal’s mid-century exodus. The population decreased from 250,000 in the mid-1920s to just over 77,000 today. The departure of the mining industry reverberates in the complex economic struggles and the too-few living-wage opportunities that long-time residents face. Although the people of Scranton take solace in sardonic humor as a coping mechanism, and rest on the laurels of their shared narrative of having fueled the nation’s homes, cities, and industries, it’s getting harder and harder for the area’s population to make ends meet.

Appalachia and other active coal-producing regions might heed Scranton’s story as a warning. Coal is not the solution to the problems of coal-mining towns; it’s the root of them. Continuing to count on coal may yield nothing but environmental woes and financial hardships.

According to the U.S. Energy Administration, coal production has declined steadily, nationally, each year since the mid-1980s. Meanwhile, industry automation makes more remaining workers obsolete. If our president truly wanted to help working class Americans, he’d embrace our nation’s investment in growing, sustainable industries and workforce training that will provide citizens with the knowledge to gain employment in high-demand, well-paying, skilled labor jobs.

Coal is dead. Let Scranton be the canary.

(Ashley Michini)

(Ashley Michini)

—

Ashley Michini is a master’s of science in social policy candidate at the University of Pennsylvania.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.