Why Philly isn’t giving up the fight for environmental justice

It was a stormy night in Memphis, Tennessee, and Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t feeling very well. He had a slight fever and a sore throat and felt exhausted after the trip that brought him to the city that would see him die.

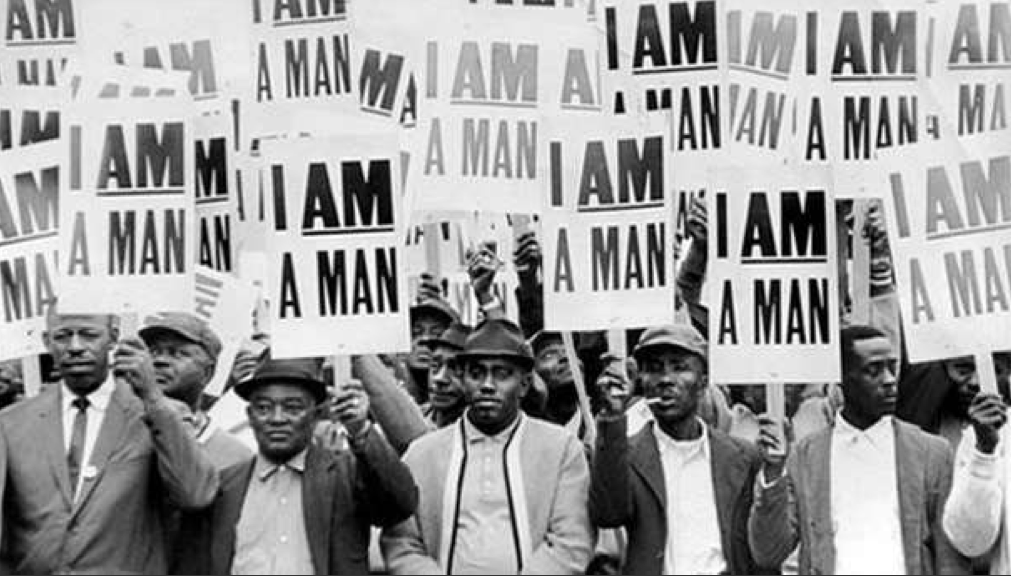

But he got up from his bed at the Lorraine Motel and joined hundreds of striking sanitation workers gathered at the Bishop Charles Mason Temple. Public garbage collectors were demanding equal rights and accusing the city of neglect and abuse. It was April 3rd, 1968, the night before his assassination, and the third time he had traveled to Memphis to support the strike. “The issue is injustice,” King said. “The issue is the refusal of Memphis to be fair and honest in its dealings with its public servants, who happen to be sanitation workers.”

The garbage workers who held signs saying “I am a man” also happened to be black.

Although the term environmental justice emerged decades after King delivered his last speech, his work is considered part of the bedrock of the movement that institutionalized the right to be equally protected from environmental hazards as a civil right.

“Dr. King was a forerunner in this area and set the tone and the stage for understanding the relationship between work and pay and civil rights and equal treatment. The civil rights movement gave birth to the environmental justice movement,” says Robert Bullard, a professor at Texas Southern University. If King was considered the founding father of environmental justice, Bullard would be his firstborn son.

But King’s legacy could be significantly affected this year.

Mustafa Ali co-founded and led the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Justice for 24 years. Cuts in President Trump’s first budget reduced the office forcing Ali to resign last spring.

Trump’s 2018 budget proposal eliminates the office completely.

“I knew more folks are going to get sick, and eventually more folks are going to die based upon the choices that they were moving forward on,” says Ali, now senior vice president of climate, environmental justice and community revitalization with Hip Hop Caucus. “I couldn’t be a part of that.”

The proposed budget zeroes out the office and imagines a reorganized agency where justice work is integrated into the agency’s other programs in a way that leads to reduced bureaucracy and faster environmental review processes.

The office change will “lead a corporate approach… that will streamline the entire environmental review process and reduce subjectivity, providing our stakeholders with more clarity and certainty on their projects,” an EPA spokesperson wrote in a statement released to the Washington Examiner.

Ali says downgrading the office will reduce the amount of support communities have as they work to protect themselves from hazards.

“We’re going back 25 years to a time when communities of color, low-income communities and indigenous populations did not’ have access to information, to decision making,” Ali says, adding that the cuts to environmental justice protection extend well beyond the EPA.

One of the communities that could be hit hard is the Overbrook section of West Philadelphia. A leafy area east of 63rd Street that is home to a largely African-American population, Overbrook grew in the 19th century as a hub for textile factories that relied on the area’s creeks as sources of water and as a dumping ground for toxic bleaches and dyes. In 2014, Ali’s office recognized the neighborhood with a $30,000 grant to support the Overbrook Environmental Education Center.

The center sits on the site of a former quarry that had become a dumping site. Fifteen years ago its neighbors turned it into a community center focused on environmental education. Jerome Shabazz is the head and heart of the organization. The site has an orchard, a greenhouse, and murals. On weekday evening and weekends, families pile in for yoga and dancing classes. And they have workshops to teach the neighbors how to grow food and protect themselves from toxins like lead.

Overbrook resident Erica Tunnell is one of the residents who was trained. Before being taught about the dangers of lead, asbestos, and mold, she didn’t know people could be exposed to lead by drinking water or spending time in their homes.

“I didn’t know that soil had certain things in it, I just thought dirt was dirt, see? But once I came here, and they gave us the knowledge and the tools, and then I volunteered to have people come, and they were testing this and testing that…. it was fascinating,” she says.

The Overbrook center can train neighbors like Tunnell thanks to an environmental justice grant they got from the EPA.

Jerome Shabazz is the head and heart of the center. He says the grant from Ali’s office allowed the organization to lay the groundwork for a major public education campaign that raised awareness about waste, water quality, lead and pollution in three Philadelphia zip codes: 19131, 19139, 19151. All three areas struggle with high asthma levels and 80 percent of the properties there were build before 1950, meaning they probably have lead paint and lead pipes.

“What we realized is that there was a big gap between truth and fiction,” Shabazz says.

Tunnell now spends time teaching her Overbrook neighbors, predominantly people of color, how to protect their own families.

“Finding this out can save your life, it can make you live longer and also possibly decrease the number of children that may be diagnosed with some kind of learning disability,” Tunnell says. “Education is power, that’s all I can say. It really, really is.”

Shabazz calls Trump’s plan to eliminate the environmental justice program “horrible for Philadelphia.”

He says that without the support of the EPA program, the center would never have been able to move forward with Overbrook Farmacy, a wellness center projected to open in 2018. The new center will improve people’s health and create 40 jobs in the neighborhood, he says.

“The reality is that the EJ division is a people-focused division,” Shabazz says. “It’s looking at issues that impact people’s lives; typically they’re folks who are quite vulnerable and do not have resources or access to information. And what it does is create collaborative models in which people who have information, such as universities and municipalities, can connect with non-profit organizations and environmental groups within a local level and allow them to bring resources to those communities where they work.”

He says that without the support of the EPA program, the center would never have been able to move forward with Overbrook Farmacy, a wellness center projected to open in 2018. The new center will improve people’s health and create 40 jobs in the neighborhood, he says.

“The reality is that the EJ division is a people-focused division,” Shabazz says. “It’s looking at issues that impact people’s lives; typically they’re folks who are quite vulnerable and do not have resources or access to information. And what it does is create collaborative models in which people who have information, such as universities and municipalities, can connect with non-profit organizations and environmental groups within a local level and allow them to bring resources to those communities where they work.”

Walking to the greenhouse, covered by snow this time of the year, Shabazz talks passionately about their new two-year program for high school students called O’Yes and dreams of all the future projects that could come. He sees himself as carrying King’s legacy by lifting vulnerable communities with information and knowledge.

“He gave them voice, and it’s important for all of us to keep that voice alive,” Shabazz says.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.