Early genetic testing can lead to better health outcomes. So why are patients of color not tested at the same rates?

Population-level and familial risks exist for inherited cancer disorders. Diversifying the genetic counseling field is one solution.

New Jersey resident, Kimyatta Frazier (middle), with her family celebrating Mother's Day last May. (Photograph courtesy of Kimyatta Frazier)

For years, New Jersey resident Kimyatta Frazier was aware of a history of breast cancer in her family. She lost her mother in August to the disease, and several aunts, as well as her maternal grandmother, were diagnosed with breast cancer. When Frazier’s mother was still receiving treatment, she underwent some genetic testing and discovered that her cancerous tumor had some genetic mutations.

“And I wasn’t clear about what that meant, but I reached out to my [OB/GYN] and asked her … should I be doing further [tests] besides just the annual mammogram because of what was happening in my family?” Frazier said.

Frazier’s mother and aunts are among the many African American women who experience a higher and earlier prevalence of breast cancer before the age of 50 compared to other racial groups. Experts say it has also been shown that Black women are more likely to have a more aggressive kind of cancer known as triple-negative breast cancer, which has a poorer survival rate.

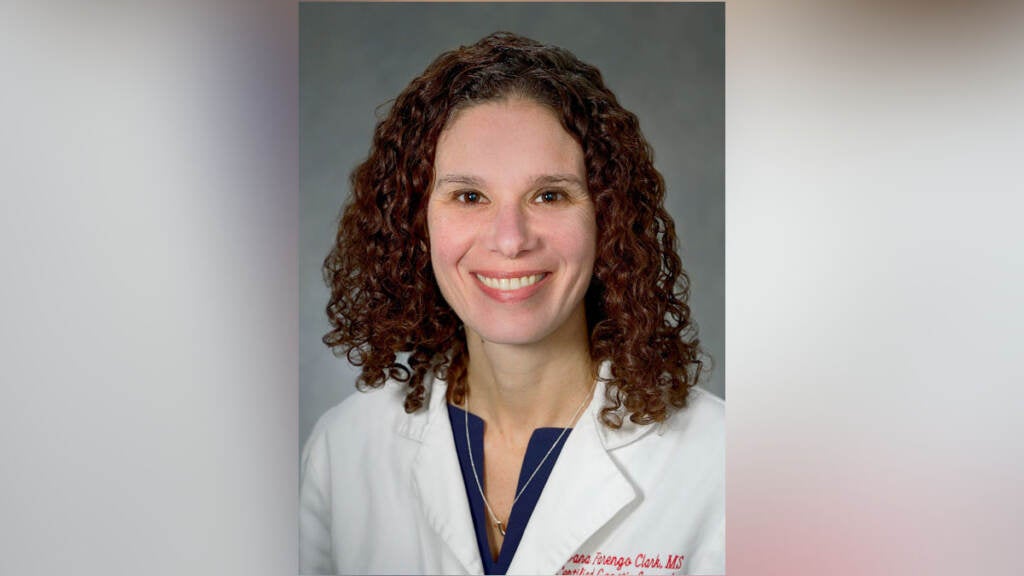

With this population-level and familial risk in mind, Frazier’s OB/GYN referred her to Dana Farengo Clark, a senior genetic counselor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center. For over 20 years, Clark has provided genetic testing for inherited cancer syndromes.

Counselors like Clark work with people who have some kind of genetic disorder, help them understand what they are at risk for, and provide genetic testing. According to Clark, research shows that Black women and white women with the same level of risk of having a specific genetic breast cancer mutation don’t get tested at the same rates. And one of the major reasons is Black women are not recommended by their doctors at the same rate white women are. This disparity also is reflected in other communities of color, where making use of genetic tests has been low. Clark said health researchers are still trying to figure out why, but one of the major barriers has been access.

Frazier had a longstanding relationship with her OB/GYN, who is also a Black woman. The trust her specialist built with her over the years encouraged Frazier to reach out to her about the prospect of genetic counseling.

“When people don’t necessarily have a routine primary care or gynecologist like [Frazier, who] was referred by her gynecologist, [and] are using an emergency room as primary care, it’s very difficult to have that family history conversation,” said Clark.

Patients of color face significant barriers to genetic testing

Traditionally, genetic counseling was housed within academic centers, so access for more rural or isolated communities was a significant challenge. Clark said there is also a pervasive myth that genetic testing is very expensive, which can deter some patients.

“Genetic testing [for cancer] used to be almost $3,000,” said Clark. “Now, it’s gotten to the point that most patients don’t pay anything out of pocket. So we really [have tried] to get rid of those barriers to care.”

In addition to those patient barriers, the field as a whole has lacked diversity among genetic counselors. Right now, 95% are white women, which may strain critical dialogue between genetic counselors and patients, whose health outcomes are often improved through interaction with medical professionals who come from similar backgrounds and can share lived experiences with their patients.

But that’s changing. In November, Penn Medicine announced that it was awarded a $9.5 million grant from the Warren Alpert Foundation to increase diversity in genetic counseling programs. This funding is the most significant award to support genetic counseling education nationwide, and will support 40 underrepresented students in five genetic counseling programs in the northeastern United States over five years, to expand all dimensions of diversity.

There is a growing understanding among health systems and doctors that having medical staff who reflect the diversity of patients served can move the needle on longstanding health disparities. Frazier said she can attest to this in her own life as a Black woman navigating the health care system. She remembered asking a medical provider for a colonoscopy and being denied the test because she didn’t meet the age requirement set for the general population at the time, which was 50. But according to the American Cancer Society, Black Americans have the highest rates of colorectal cancer when compared to other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, and are 40% more likely to die from this disease as well. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends that Black Americans begin screening at age 45, not 50.

“I got pushback for the request to get a colonoscopy before I turned 50,” said Frazier, who added that perhaps having a Black provider who was sensitive to this particular disparity would have been the difference in getting approval for the test earlier.

In the U.S., genetic counseling has traditionally been conducted in English, which also has created issues for patients for whom English is not their first language. Clark said the field has provided translators during patient consultations, but even that has its limits.

“It’s really important to have someone who understands not only the language, but the culture,” Clark said. “You know, there are things that I don’t understand that aren’t part of my background, [and] I think it would be really nice for people to be able to speak to someone who understands … social differences and just a lot of different traditions.”

‘I felt a little bit ahead of the game’

Frazier initially met with Clark in August over Zoom to discuss her potential genetic risk for breast cancer, and she recently recalled being flooded with feelings of anxiety. She didn’t know what to expect. During that first consultation, Clark explained how the test would work, if there were any out-of-pocket costs, where Frazier could get the test, and what the next steps would look like if the test came back positive. They scheduled an appointment together, and a week later Frazier had her blood drawn at Penn Cherry Hill Laboratories. The blood sample was then sent to a third-party lab to be reviewed.

“The time came, and I figured no news means good news,” Frazier said, “But then [Clark] left a message, `I would like to discuss your results.’ I was a little nervous because I thought if everything was OK, she would say everything was OK.”

During Frazier’s follow-up appointment, Clark explained that the test had come back negative but that she preferred to discuss results in person, regardless of the outcome. Because Frazier has such a significant family history of breast cancer, Clark suggested that Frazier continue with her routine annual mammograms, in addition to MRI screenings and routine checkups with a doctor at Penn Medicine’s Basser Center for BRCA.

As she reflects back on the whole experience, Frazier said, she feels lucky that she can take this preventative step to get genetic testing before any kind of cancer has the chance to strike.

“My mother [and my] family members … didn’t get the genetic tests until after their diagnosis,” said Frazier. “So I felt like I’m a little bit ahead of the game. But still, I’m still very cautious because as far as mammograms go, the area where [my mother’s] tumor was found couldn’t have been seen on a mammogram at that time.”

Efforts to make genetic testing more accessible

Frazier, who is a registered nurse, has also been encouraging other family members to get genetic testing. Those conversations have been important in making other Black family members aware of the testing as an option, she said, but she wonders why it’s not just part and parcel of routine primary care visits.

Clark said that’s something health systems are trying to do.

“I think the problem traditionally has been that [primary care doctors] don’t know which tests to order,” said Clark. “They have like 15 minutes with patients through no fault of their own, they don’t know what lab to send [the tests] to, they don’t necessarily know how to interpret the results.”

Efforts are underway to streamline the process of ordering tests through non-genetic counseling providers. But Clark said that on the patient side, there can be stigmas within families about their histories with particular diseases that can impede access to care in the first place. Sometimes, she said, there’s a culture or attitude that encourages people not to talk about family medical problems, to the point that some family members may not even be aware of a certain genetic risk they have.

“So sometimes, I think people don’t come because they say, `Well, I don’t know anything about my family,’” said Clark. “But I really feel like it’s important for people if they feel like this is something they want to know … be proactive, ask the questions. We just want to increase referrals among all patients.”

___

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.