Dylan Elchin was 8 years old when the war in Afghanistan began. He was eager to serve.

His death is still setting in for his family and community in western Pennsylvania

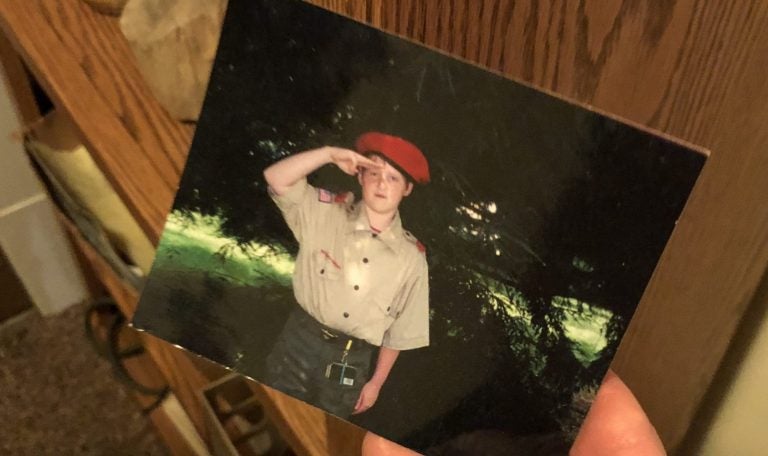

Dylan Elchin is seen as a child in this photograph, wearing a Boy Scout uniform and red beret. Years later, he would earn the honor of wearing a scarlet beret as a combat contoller in the Air Force. (Ed Mahon / PA Post)

This story originally appeared on PA Post.

—

Ron Bogolea lived next door to his grandkids for years in rural Beaver County, surrounded by woods and farms, and he’d take Dylan Elchin and his brothers into the outdoors for hiking and other adventures.

“When they’d get tired, you know, I’d push ’em and push ’em and push ’em,” Bogolea said, and recalled Dylan. “And he had the ability to not complain, not whine, and to push harder, and harder.”

Bogolea talked about Elchin, who died more than three weeks ago while serving in Afghanistan, at his home in a town called Freedom.

It’s not where Elchin grew up. Bogolea moved about five years ago and now lives in a home atop a steep hill with a view over the Ohio River.

Inside, a photo of Bogolea and Elchin is on a living room wall. Elchin wore a military uniform and a scarlet Air Force beret — a beret that reminded Bogolea of one Elchin wore years earlier as a Boy Scout.

Elchin spent years preparing for the military and to serve in the special forces.

“With the special ops, it’s, it’s not your size,” Bogolea said. “If you look at these guys, they’re not big guys most of (them) — there are few big guys. But it’s the guts. It’s the heart that you have if you can make it or not. And apparently Dylan had that.”

Elchin knew the risks.

He told his mother that if people from the military ever showed up to her front door in civilian clothes — don’t worry, that just meant he was hurt. But if they showed up in their uniforms, then it was bad.

Elchin kept in touch with his family during his first deployment to Afghanistan. In late November, he talked with Bogolea and other family members on a video call. Then, on Nov. 27 near Ghazni city in east-central Afghanistan, a roadside bomb detonated near a vehicle Elchin was in, flipping the mine-resistant and ambush-protected vehicle, The New York Times reported.

Elchin was 25 years old and planning to get married when he returned to the United States.

For the family, his death is a reality that is still setting in.

“Sometimes, you know, you kid yourself. ‘Well, he could be right out there now,’” Bogolea said, pointing to the front door of house. “But you know he isn’t. But … I guess we want to play tricks on ourselves.”

Three other soldiers, including another one from southwestern Pennsylvania, died from the attack — the deadliest on American forces in Afghanistan this year.

Since 2001, more than 90 soldiers from Pennsylvania serving in Afghanistan war operations have been killed, according to Department of Defense conflict casualty records. And Elchin is the third soldier from Beaver County to die there.

For some, the soldiers’ deaths are reminders that, 17 years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the United States is still at war in Afghanistan with no clear end in sight.

And that’s a reminder that people like Elchin — raised in a small Pennsylvania town, a former Boy Scout, a jokester in his family, a dedicated and confident soldier — are still risking their lives overseas.

Old high school yearbooks were stacked in Carrie Rowe’s office on a recent December day. She put notes in the books to mark the pages with photos of Elchin, before he grew a thick beard and put on fatigues.

“In my mind’s eye, he’s still that young man,” Rowe said.

Rowe came to the Beaver Area School District in Beaver County nearly 20 years ago as a Spanish teacher. She’s now the district superintendent. The county, with its population of about 170,000, sits on the Ohio border northwest of Allegheny County.

It is a rural and suburban area with two tiny cities of less than 10,000 people each.

The Ohio River connects with the Beaver River in the northern part of the county. Steel dominated here before the industry collapsed.

Now, the natural gas industry is changing the region. Red cranes for the construction of a multi-billion dollar petrochemical plant have changed the skyline, a sign of the resurgence.

Elchin spent most of his school life in the Beaver Area schools, before he moved to a nearby school district for his senior year of high school.

Grant Mundy, now a 25-year-old teacher in the district, went to school with Elchin.

They sat together at lunch in middle school. They played in the band together — trumpet for Elchin, saxophone for Mundy. They went bowling, played a Mario Kart video game, hung out by a creek that runs through the school grounds, pretended they were in the secluded wilderness — that kind of stuff.

Rowe was their middle school principal.

She said Elchin was curious and liked to build things. And he was kind — he was part of a group that sent holiday cards to a school for students with intellectual or physical disabilities.

When Elchin was about 15, he started reading books about special operations work. Later, he connected with a military recruiter and told him he wanted to join special operations. The recruiter took him to the local YMCA to train. He swam, lifted weights, ran and got ready to join.

Bogolea served in the U.S Army for three years during the Vietnam War. One of Elchin’s older brothers, Aaron, served in the Pennsylvania Army National Guard.

But Elchin’s passion for the military was his own, they said. It likely came from the service and rituals of the Boy Scouts.

“They teach you a lot of moral values,” Bogolea said. “They teach you honor and honoring your country.”

Aaron described two sides to his brother: He could be goofy and funny about 75 percent of the time. And when he needed to be serious and focused, “he could switch that on and off pretty easily,” Aaron said in a phone call from Ohio, where he lives.

Elchin graduated from high school in 2012 and, a few months later, enlisted in the Air Force as a special tactics combat controller.

He immediately entered a two-year combat control training program.

Elchin was assigned to the 26th Special Tactics Squadron at Cannon Air Force Base, New Mexico.

Air Force Master Sgt. T.J. Gunnell spent about a year-and-a-half as Elchin’s troop chief.

“You could give him the worst job ever, and he’s just going take it, do a great job, come back to you with just an incredible product and say, ‘Hey, I crushed this. What else can I do for you?’” Gunnell said.

Elchin was eager to go overseas. “He wanted to get after it. He was hungry,” Gunnell said.

In July, before Elchin deployed to Afghanistan, he spent time back in Beaver County. He and Bogolea spent hours talking outside one day.

Elchin told his grandfather that he had a whole lot more confidence in himself since going through the training.

“I think he was trying to tell me, ‘Even though I’m going to Afghanistan, don’t worry. I’ll be back,’” Bogolea said.

Now, Sandy Bogolea said she goes from sad to mad to proud some days.

Hundreds of people attended a memorial service for Elchin earlier this month. Motorcycle riders escorted the family. Airmen performed pushups in honor of Elchin.

Ron and Sandy Bogolea heard from teammates of Elchin’s in New Mexico as they were building a makeshift boat to burn in Elchin’s honor — a Viking funeral.

Jessica Davis, a 38-year-old first sergeant in the U.S. Air Force Reserve, served overseas in Kuwait and then Iraq twice. She’s now working on creating a monument in Beaver County for Elchin and other soldiers who have died in the Global War on Terror.

Davis has seen the impact of Elchin’s death, especially with some of the younger military members in the area. When they enlisted, they knew dying overseas was a possibility.

“But I think a lot of them are still … reeling, like, ‘Wow, this is something that, you know, could happen to me. It could happen to my friends, it could happen to my family,’” Davis sad.

But at the same time, Davis said, they also know Elchin died doing what he loved.

For Elchin’s family, there are big changes and small ones. Ron Bogolea used to love watching a cable channel that showed World War II and other war documentaries. He’s not interested in that anymore.

In July, Dylan Elchin visited the Bogoleas’ home. There, on a recent night, Sandy and Ron Bogolea and one of Elchin’s brothers, Ryan, sat in their living room and talked about Elchin and the war in Afghanistan.

“Well, the problem over there is there are no distinct battle lines,” Ron said.

“It just goes on and on,” Sandy said.

Ron continued talking about the war, sometimes with Sandy adding comments, sometimes connecting things with Dylan.

“It’s somewhat of a guerilla war,” Ron said. “…It’s not a conventional war where you can say, ‘Well, there’s the bad guys, if we get rid of them, we’ll win.’”

“There’s always more,” Sandy said, and then brought up Dylan. “And didn’t he go back to the same place he almost got killed in August? He went back to the same town.”

“Yeah, he went back to the same city,” Ron said.

When Dylan was alive, this kind of talk — about the dangers he faced overseas — wasn’t something he really went into detail about. He would rather talk about the training.

But his family has heard the stories behind the Bronze Star and other medals he earned over there and the stories of how he approached his missions, how he risked his life to identify the enemy’s position and call in air support, how he had no complaints after spending four days in the field without sleep or relief.

News accounts have described what’s happening there now. The U.S. and Afghanistan government forces have been fighting for control of the Ghazni region near Pakistan in recent months, with Time magazine writing in August that the Taliban assault on Ghazni “was the most orchestrated operation of this nationwide onslaught.” That article was published the same month that Elchin deployed.

In November, the roadside bomb that killed Elchin went off outside Ghazni city. The New York Times reported that the attack was well coordinated, with the bomb going off in the middle of a joint Afghan and American convoy.

For Bogolea, the war in Afghanistan is a way to prevent terrorists from attacking in the United States, at malls, at schools, at football games, anywhere else. There’s evil in the world, and the United States needs to protect itself.

“Whether or not we’re doing it in the exact, right strategic way — who knows? There’s smarter men that worry about that than me,” Ron Bogolea said. “But it’s got — we’ve got to continue to keep it contained over there.”

That, Bogolea said, is what his grandson was fighting for.

PA Post is a digital-first, citizen-focused news organization that connects Pennsylvanians with accountability and deep-dive reporting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.