New possibilities for the once grand hotel Divine Lorraine

-

<p>Developer Eric Blumenfeld speaks to a small group gathered in the main lobby of the Divine Lorraine Hotel. Bluemenfeld wants to revitalize a portion of North Broad Street centered around the old hotel. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Bill Deasey, director of leasing for EB Realty Management, leads visitors up the marble staircase of the Divine Lorraine. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Tumbled bricks cover the area where devleoper Eric Blumenfeld says a statue of Father Divine once stood. The religious leader bought the hotel in 1948. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Developer Eric Blumenfeld says he has plans to restore the original decorative details of the Divine Lorraine if he moves forward with his plans for North Broad Street. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>The inner courtyard of the Divine Lorraine Hotel. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Eric Blumenfeld (left) describes plans for improving the building's surroundings to George Farrell, special assistant to Pa. Sen. Lawrence Farnese; Masterman School parent Steven Bayne; and Karen Lewis, executive director of Avenue of the Arts, Inc. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>If Eric Blumenfeld, the new owner of the Divine Lorraine Hotel, goes forward with his plans, the hotel will be at the center of a more comprehensive idea for revitalizing part of North Broad Street. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>The Divine Lorraine Hotel at 699 N. Broad St. opened in 1894 as an apartment building. Developer Eric Blumenfeld has plans to make it an apartment building again. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>These tiles were salvaged from the Divine Lorraine Hotel and are now at Provenance Architecturals, LLC, a warehouse that resells architectural salvage. (Kimberly Paynter/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>These tiles were salvaged from the Divine Lorraine Hotel and are now at Provenance Architecturals, LLC, a warehouse that resells architectural salvage. (Kimberly Paynter/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Mantle pieces salvaged from the Divine Lorraine Hotel are now in storage at Provenance Architecturals, LLC, a warehouse that resells architectural salvage. (Kimberly Paynter/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

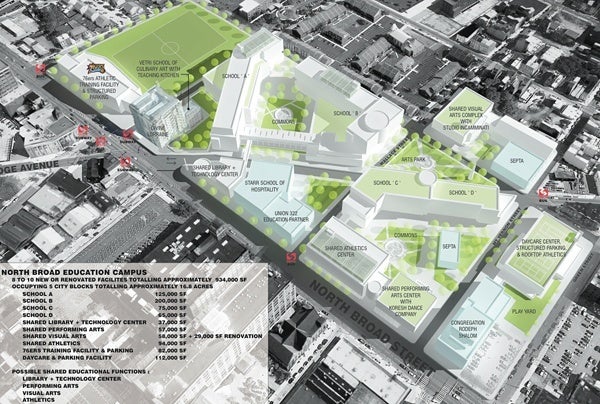

<p>Artist rendering of developer Eric Blumenfeld's plan for the area around the Divine Lorraine Hotel. Neighbors around North Broad Street worry about their properties being swallowed up by the development.</p>

-

<p>The Calderwood Gallery closed one store and expanded this location two years ago, with hope to do more with the building. (Nathaniel Hamilton/For NewsWorks)</p>

-

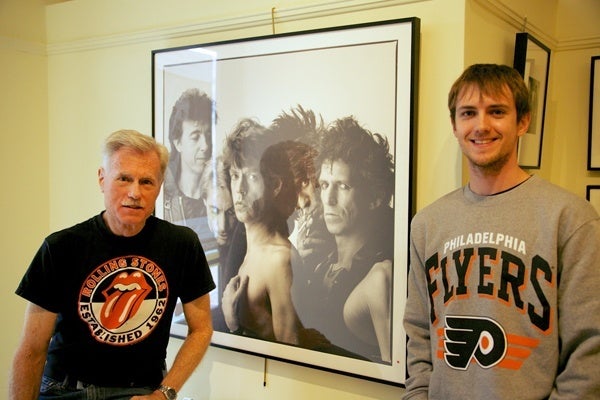

<p>Gary Calderwood and his son Christopher. Calderwood and his wife Janet own Calderwood Gallery on North Broad Street, but the building is not included in Divine Lorraine owner Eric Blumenfeld's plan for North Broad Street. (Nathaniel Hamilton/For NewsWorks)</p> <p> </p>

The Divine Lorraine looms over North Broad Street like a gigantic contradiction. Graffiti tags mar its grand facade from street level to towers. Its shattered windows open into a hulk of a building long-since gutted by scavengers and failed renovations.

Clearly crumbling toward an unpleasant end, the Divine Lorraine’s mortality seems self-evident.

But don’t try telling that to developer Eric Blumenfeld. When he looks at the 10-story tower, he sees only possibilities. To him, the building holds the key to a massive renaissance that would restore North Broad Street to the grand boulevard it was when the brand-new Lorraine Apartments opened in 1894.

And don’t try telling that to Temple University student Dean Nani. The Lorraine has so mesmerized him that he wrote a college research paper on it and now speaks of Blumenfeld with the fervor of a groupie.

Plans for this North Broad revitalization seem to be just beyond the dream phase. To make them real, Blumenfeld must raise a lot of money and acquire a lot of land, and folks who live there now must be convinced that his grandiose blueprint works for the neighborhood.

Nani, however, harbors little doubt. He admires Blumenfeld’s efforts so much that he recently popped up as the developer was offering a tour of the premises.

How had he known Blumenfeld was there?

Well, he’d read a lot about Blumenfeld and when Nani emerged recently from the subway, he could tell that someone was in the building. Seeing Blumenfeld’s flashy ride, Nani put two and two together.

“I knew that he was into fancy cars — and I saw it parked out front and knew that he had to be here,” Nani said, “So I’ve been here for the last 45 minutes waiting for him to come out.

“I just wanted to meet him. This is my favorite building in Philadelphia. I think North Philadelphia really needs something like this right now. And it comes at a perfect time.”

A minute later, in an oddly tender moment, the student and the developer hugged.

A pioneer of distinction

As much as anything, that scene, of an ambitious developer embracing a college student he’d just met, sums up the Divine Lorraine’s magnetism. It also puts a fine point on just how important Temple University — just eight blocks north — is to any North Broad plan.

Ken Finkel of Temple’s American Studies program says this building was built to make a statement, and to be a destination. Witness its construction materials: buff-colored brick and limestone.

“The material is different. It’s not red brick like the rest of the city,” Finkle said. “They specifically didn’t want it to look like anything else. Its forms are a lot of play with arches and windows and the two towers. The Divine Lorraine predates the turn of the century, predates World War I. So it’s a real pioneer.”

The building spent its first 50 years as a well-appointed apartment house. In 1948, Father Divine, the charismatic leader and self-proclaimed deity who ran the Universal Peace Mission Movement, bought it.

“Because of its role with Father Divine’s mission, and that continued for quite a while, it was a truly functional, viable almost quasi-utopian community,” Finkle said.

A fiery preacher, Divine, a black man married to a white woman when such marriages were not accepted, built a community around tolerance. He reportedly said, “I am not a race nor a creed, nor a color; but as a supernatural power, as infinite spirit, as universal mind substance I came! I am redeeming the children of men.”

Finkel said Divine changed his followers’ lives. “People would really turn their lives, their wealth, their assets, over to this collective community. And they would eat together and pray together.”

Philadelphia City Council and social and political leaders across the country lauded Divine and his group’s work, while some questioned his followers’ extreme dedication. The controversial social trailblazer and civil rights advocate also claimed to be God and, in addition to many faithful followers, he drew critics who considerd the utopian religious movement a cult and Divine its power-hungry leader. In 1950, Divine opened another building in Philadelphia: the Divine Tracy Hotel.

In 1953, the group expanded, purchasing Woodmont, which became Divine’s home. The building, which Divine dedicated as the Mount of the House of the Lord, sits near the Philadelphia Country Club in Gladwyne and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1998.

In keeping with his religious and social beliefs, Divine is believed to have ended his correspondence with: “Sincerely wishing that you and those with whom you are concerned might be even as I am for I am well, healthy, joyful, peaceful, lively, loving, successful, prosperous and happy in spirit, body and mind and in every organ, muscle, sinew, joint, limb, vein and bone and even in every atom, fibre and cell of my bodily form.”

In July 7 1940, The Savannah Journal‘s editorial page reportedly singled Divine out for his historic leadership role:

“There are those who have criticized Father Divine and condemned his movement, but despite what has been said and written, he stands today as the greatest and most powerful single force in America. There is only one other man in the world who ranks with the little man of peace in Harlem, and that is Hitler. The difference between the two is: Father Divine believes in right, in peace and a form of government in which all enjoy liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Hitler believes in war, bloodshed, uses his power destructively instead of constructively.”

The racially integrated community sold the building in 2000, and the intervening years have been tough on the Lorraine. Most of the furniture and fixtures have been stripped. But even decades of neglect have not robbed the Lorraine of a natural grandeur, with wide open spaces and impressive skyline views.

It’s a space that, even still, takes visitors’ breath away. But some preservationists and neighborhood residents worry the building can’t survive in this shape much longer.

Another try for Blumenfeld

Blumenfeld owned this building before. Standing inside, pointing out the paneless window, he imagines the makeover he’ll give this rundown palace.

“It’s represented, for 15 years, blight. And it’s visible blight. So the transformation of this building, I think, just has such a multiplier effect not only on the development of the North Broad Street corridor but Philadelphia in general,” he said. “Because this is really a convergence of multiple neighborhoods, and we’re really the link between Temple University and downtown.”

And that’s the thing. For North Broad Street to return to its glory days — or at least to attract shoppers, diners and residents from across the area — many say the Divine Lorraine must be reborn. It’s the linchpin, the keystone.

“This is a tremendously blank canvas,” he said of the gutted structure. “Some guys come in and they just close it up with drywall. Well that’s the last thing we’re going to do!

“This to me feels like a museum. And if the folks who live here get that sense then I have done my job. That’s my mission.”

While Blumenfeld wants the Divine Lorraine to feel like a museum, Philadelphia Salon director Caryn Kunkle wants it to actually house one.

“We’re working on building a museum of contemporary art and we’re working with Eric to incorporate that into the Divine Lorraine,” Kunkle says. “The museum will most likely be adjacent to the Jose Garces restaurant on the first and second floors and then the sculpture garden.”

North Broad neighbors wary

It’s just one of many ideas for the building and the surrounding land, ideas that could change the life on North Broad Street.Some people who already live in the neighborhood are waiting to see what Blumenfeld does next. The developer produced a big plan that includes schools, a visual arts complex, a performing arts center, an athletics center, a library and a training facility for the Philadelphia 76ers. The entire landscape of North Broad Street looks different on his new map.

But it’s a pricey project that’s likely to require public funding — a battle that’s sure to be controversial — or other financial assistance. Blumenfeld has stressed that these are all just ideas and he doesn’t want to force out anyone who is there now.

Temple’s Ken Finkel says Broad Street was once a prominent address — a lot of people wanted to live there. Who knows? he says. Maybe they will again.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.