Diverse casting helps us understand the richness of the human story

The production of "The Diary of Anne Frank" at People’s Light and Theatre in Malvern, Pa., which included a multiracial ensemble of actors, stirred controversy.

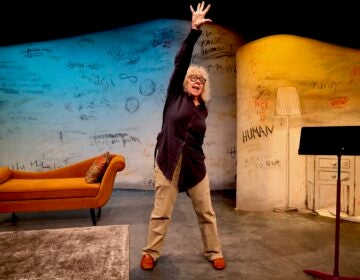

The cast of "The Diary of Anne Frank." (Photo by Mark Garvin)

I’m sure Lin-Manuel Miranda didn’t plan to write a Passover song.

But a week before the first Seder, as I was humming along with the “Hamilton” soundtrack on a long drive back from New Jersey, I heard “The Story of Tonight” anew:

“Raise a glass to freedom/something they can never take away … Raise a glass to the four of us/tomorrow there’ll be more of us/telling the story of tonight.”

In the Seder, which celebrates the Jews’ exodus from slavery in Pharaoh’s Egypt, we tell of four children who approach the holiday with reverence, skepticism, curiosity, and silence. We drink four cups of wine. We tell the story: the same story each spring … and not the same story, because we, and the world, have been altered by whatever the prior year did to us.

“Listen to this!” I said to my partner in the car that night. “I’m putting that song in our Seder.” And I did (after the dipping of potatoes in salt water and before the matzo sandwich), singing in exuberant chorus with my cousins — ages 14, 12 and 9 — who know “Hamilton” by heart.

Earlier that day, after boiling matzo balls and helping my mother unfold 23 chairs, I slipped out of Seder prep to catch one of the final performances of “The Diary of Anne Frank” at People’s Light and Theatre in Malvern.

The production, which included a multiracial ensemble of actors, had stirred controversy among theater-makers and theater-goers; one local critique admonished that “Anne’s story isn’t multicultural; it’s Jewish … there is a danger in removing or reducing Jews from the Holocaust.”

At 13, I pored over “The Diary of Anne Frank,” haunted not only because the author was exactly my age, but because she and her family were Jews, with Stars of David pinned to their shabby coats. While the original 1955 script stripped the diary of its Jewish emphasis (and some of its writer’s more intimate disclosures), the 1997 adaptation by Wendy Kesselman (the version used by People’s Light) restored both Anne’s candor and the unapologetically Jewish references.

I wondered: Would the diverse casting bring “universal” themes of oppression to the foreground and overshadow the anti-Semitism that raged in 1944 (and has flared in the United States and elsewhere since the 2016 election)?

I also thought about the flip side of that concern — that is, would playing historically specific, white, Jewish characters render the actors’ own races invisible? Would the casting enlarge and complicate the story, or would I be teased into a kind of color blindness, a lullaby that negates history and its race-based inequities?

Here’s what happened: Not for a second did I forget that the Franks and their attic mates — Mr. and Mrs. van Daan, along with their son, Peter, and the dentist Mr. Dussel — were Jews. They sang the Hanukkah blessing in flawless Hebrew (thank you, dialogue coach); they fantasized about eating latkes instead of watery kale soup; they voiced their fears about trains “headed east.”

At the same time, when Miep Gies (the righteous gentile who helped hide the Franks, played by African-American actor Danielle Leneé) showed up with ration coupons and grim news from outside, I thought about the Underground Railroad and the civil disobedience of whites and blacks who helped usher enslaved people to freedom.

I thought about Japanese-Americans whisked to internment camps, a historical stain that was blotted from my high school history texts. I thought about Carmela Hernandez and her four children, under threat of deportation, sequestered since mid-December in Philadelphia’s Church of the Advocate.

And I thought about the 1969 Freedom Seder that was, in part, the inspiration for People’s Light’s vision of this play, a Seder that made explicit connections between the Jewish Exodus and the civil rights movement.

Our stories layer, amplify, and intersect. Martin Luther King Jr. reprised Old Testament passages in his “I Have a Dream” speech. I’ve attended Seders reconstructed to highlight gender violence, immigration rights or the Spanish Inquisition; for me, those connections deepen, not dilute, the holiday’s meaning and relevance.

What stories must we tell, and how shall we tell them? We are different every year — remade by our sorrows, our grievances, our understandings — and the changed world demands new angles of approach.

What I hope is that the actors of color who rendered the characters of “Anne Frank” so faithfully can audition for broad-minded directors and land all manner of classic roles — King Lear, Lady Macbeth, Willy Loman, Elizabeth Proctor — if that’s what they want.

But I also hope that producers and artistic directors (still a predominantly white male coterie) will stage more stories that capture the widest, wildest terrain of human experience: plays by and about and featuring women, queer, and trans people, individuals with disabilities, people of color, immigrants from everywhere, the old, the poor.

“Tomorrow there’ll be more of us/telling the story of tonight” — a lyric written by a Puertorriqueño to be sung by a multiracial cohort of actors portraying the idealistic, imperfect, white agitators of the American Revolution. Miranda didn’t mean to write a Seder song. But I’m certain he knows there is more than one story of tonight. Or any night.

I knew how “Anne Frank” would end. But the play’s final scene undid me, as I watched a man with a swastika armband bully the family members — screaming, pleading, clinging — from their hiding place.

The horror is that the Franks and van Daans (and six million others) were killed simply because they were Jews. But I wept because this production underscored the crime of reducing anyone’s humanity to a single trait. I cried because Anne Frank was a person (curious, irritable, ebullient) who kept a diary, and dreamed of being a writer, and wanted to live.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.