Dirty Little Secrets: What’s wrong with the fish?

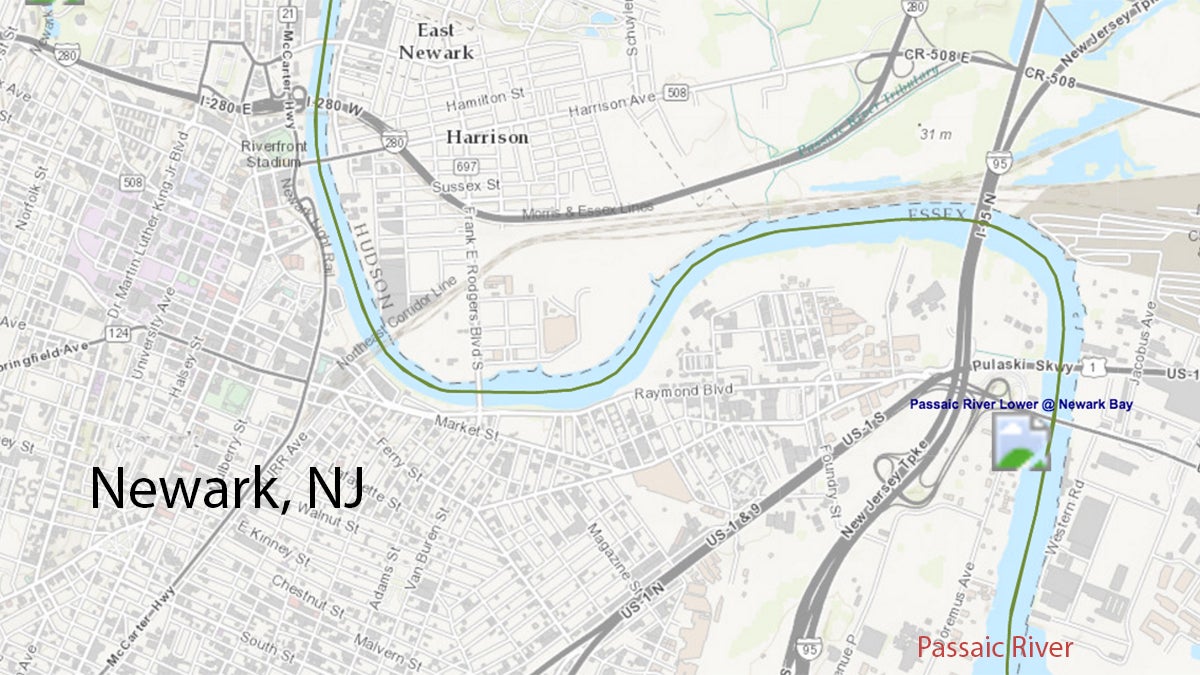

Standing on the bank where the Passaic River meets the Newark Bay in New Jersey, Oswaldo Avad reels in a small bluefish and a piece of a grocery bag.

Standing on the bank where the Passaic River meets the Newark Bay in New Jersey, Oswaldo Avad reels in a small bluefish and a piece of a grocery bag.

“One piece plastic and one fish,” Avad said in broken English.

The Passaic River is one of the most contaminated bodies of water in the country. More than 100 companies are potentially responsible for dumping toxic waste in it for decades before that was outlawed.

Eating any fish from the Lower Passaic can cause cancer, liver damage, birth defects and reproductive issues. But Avad does it all the time.

“I wash them, salt them, cover them in garlic, fry them,” he said. “Or I make a soup.”

Now, some of the companies responsible for polluting the Passaic are funding a fish exchange program.

Every Saturday between June and October, residents can bring their contaminated catch to a tent in Lyndhurst and swap it for clean, healthy tilapia being raised in a greenhouse in Newark. But in 2015, none of their 300 tilapia reached harvest size, so the polluters handed out frozen tilapia fillets from Costco instead. And they’re not sure how to dispose of the contaminated eel, carp, perch and crab they’ve collected.

Byproducts from the manufacture of compounds like Agent Orange and hydraulic fluid were dumped in the Passaic. Fifty-four companies who are potentially responsible, including Pfizer, Rubbermaid and Tiffany & Co. have combined to form a group called, “The Lower Passaic River Study Area Cooperating Parties Group.”

They’ve spent $1.1 million voluntarily funding the fish exchange and greenhouse project. The waste produced by the fish is also used to grow lettuce and herbs for a local food bank.

“It will be years before the fish can be consumed safely,” said Jonathan Jaffe, a spokesperson for the polluters. “So until that time we are trying to reduce risks to the most vulnerable in our community.”

Since June, the polluters have prevented just 170 contaminated fish from being eaten.

Opponents say they’ve hardly made a dent. And all the contaminated fish they’ve collected are now sitting in a freezer in Newark with no disposal plan.

“They could just go to a landfill,” said Any Rowe, an environmental chemist at Rutgers University who runs the fish farm for the polluters. “They could be buried somewhere in New Mexico. There are all kinds of ways to get it out of Newark.”

Legally, the contaminated fish can go in the trash where they would end up being burned. But environmental justice advocates warned contaminated fish better not end up in their incinerator.

“You breathe in what comes out of the smoke stack,” said Molly Greenberg, the environmental justice coordinator with the Ironbound Community Corporation. If it’s toxic when you eat it, it’s toxic when you burn it and breathe it.”

Advocates think the fish exchange is a distraction tactic to avoid cleaning up the Passaic. but the polluters and Walter Mugdon with the EPA agree the fish swap is not a solution.

“It’s not something that we’ve proposed nor is it something that we endorsed,” Mugdon said. “It’s certainly no substitute for cleaning up the river and getting the fish to be cleaned in the first place.

The EPA wants the polluters to replace two feet of toxic mud from the river-bottom with clean rocks, sand and gravel. It’s a $1.7 billion clean-up — one of the largest proposed sediment removals in the history of the EPA’s Superfund program.

The polluters want to fund a cheaper, targeted clean-up that spokesperson Jaffe calls “a sensible alternative” that would “use science to direct the remediation.”

Jaffe said that the EPA’s proposal is, “destined for years of conflict and litigation.”

But the EPA says the polluters don’t get a say.

“We make the decision,” Mugdon said. “That’s not something that we negotiate.”

Meanwhile, it could be decades before the fish is safe to eat again. And residents like Oswaldo Avad don’t often think of the potential health risks.

“I’ve been eating this fish for eight years,” Avad said. “I feel fine.”

This story is part of Dirty Little Secrets, a series investigating New Jersey’s toxic legacy. Participating news partners include New Jersey Public Radio/WNYC, WHYY, NJTV, and NJ Spotlight. The collaboration is facilitated by The Center for Investigative Reporting, with help from the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State.

Find toxic sites near you, here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.